This “Romenomics” series aims to study commerce in ancient Rome - including some details which are unique, humorous, and enlightening - in order to better appreciate the economic present.

Caput Mundi wasn’t always at the top of the economic heap. Ancient Rome had a long and arduous journey over its more than 1,100 years of existence. First, it made baby steps as an ambitious network of villages at her founding in 753 B.C. Then, it flexed its political brawn during an unstoppable Republican expansion across the Mediterranean basin for half a millennium. Finally, it spent 500 years as an omnipresent and almighty, though often dysfunctional, Empire that occupied 25% of the then-known world. She finally fell under the weight of her own moral, political, and economic decay following the deposing of the last Western Emperor, Romulus Augustus, in 476 by invading barbarians.

Like Rome’s ancient Latin language, which we still study for a deeper comprehension of our own modern tongue, so too is it worthwhile to reflect on economic antiquity to understand why some fundamental economic laws of markets and related cultural systems have lasted as long as the Eternal City herself.

One caveat emptor: Many naively buy into the glory of ancient Rome. They are starstruck, seeing her through a prism of triumphal arches, marble palaces, sprawling fora, and iconic busts of men who brought order, peace, and prosperity to a primitive era of human history. We think this, despite knowing that pagan Rome was often no better – at least morally and spiritually - than the so-called barbari she conquered.

So, too, we often put on the same rose-colored glasses when it comes to the ancient Roman economy. No doubt, it created the first functioning transcontinental commonwealth and was the first real attempt at globalization, but her commercial life certainly not always impervious to crises nor divinely led by godlike business gurus.

Still, the fascination is that the colossal Roman economy worked at all, let alone so well, for so long, with a steady flow of invention, connectedness, and wealth creation across three continents. In this Romenomics series, I will look at several major factors of the ancient economy, namely:

- Labor and wages;

- Centers of commerce;

- Market sectors;

- Supply, demand, distribution;

- Prices, controls, inflation;

- Currency and monetary policy;

- Taxation and subsidies;

- Commercial Law;

- Faith, risk, and the "gods" of Commerce; and

- Economic miracles and disasters

Romenomics 1: Labor and wages

Since he heart of any functioning market – ancient or modern – is human talent and production in exchange for compensation, it makes good sense to start with an overview of trades, professions, industries, and daily services that existed in ancient Rome, including unpaid or forced labor (servitutem). Unless you’ve never opened a classical history book or watched an epic film like Sparticus, you are certainly aware the Roman economy depended heavily on slavery for huge percentages of its economic output, for both private and public works. At the height of the Roman Empire, the GDP was estimated at today’s equivalent of $32 billion. Slave labor accounted for roughly 20-30% of economic activity during the period of greatest state-sponsored construction (roads, stadiums, theaters, temples, civil engineering), as during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian, which built some of Rome's longest-standing monuments.

Slaves – servi – also provided a number of services about which today no one today would complain excessively, especially because they are now well-remunerated: cooking, hairdressing, massage therapy, and even technical assistance to professions such as lawyers, mapmakers, engineers, and even those who assisted with the nomenclaturae for keeping track of huge networking lists of names and associations for politicians and business elite (much like an ancient Rolodex or today's social media profiles).

It goes without saying that servi performed “death-defying” entertainment (gladiators/charioteers) and food safety/quality assurance (testing for poisoned food and drink). Female slaves were sometimes forced into prostitution or its softer domesticated form – contubernium – a relationship in which a master lived in an open domestic relationship with his slave.

So what did the cives – the free citizens – do for a living? First of all, many of them – especially the lower ranking plebeii – lived in worse conditions (the insulae slum housing) than the servi owned or were given by the patricii nobles. They had to work hard for a very modest standard of living. Plebeian jobs were not much different than today’s blue-collar ones or “mom-and-pop” small enterprises. They ran small shops, market kiosks, and taverns; they rented mules; they farmed small plots; they were the chariot “mechanics,” maintained horse stables, and performed secretarial and logistical duties. Some were low-paid but important guides in the newly conquered foreign lands. For the most part, plebeians were your everyday repairmen, suppliers, and basic service providers.

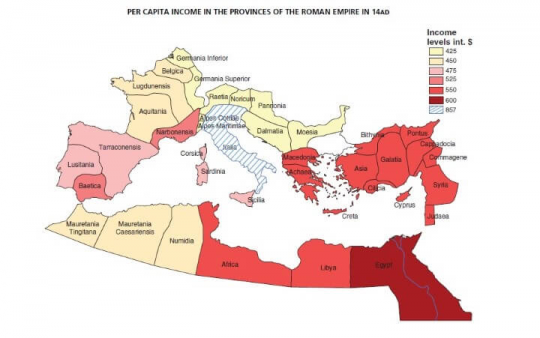

But what were plebeian wages like? One thing that classical economists have tried to estimate is per capita income during the imperial Golden Age. Some estimate yearly earnings of early first-century Rome at today’s conversion: $570. That's not very much, even if bread and many other heavily subsidized staples were cheaper, often free. Virtually the entire empire lived well below the poverty level. Like today, a lot of income was earned “under the table” and not reported officially to avoid tribute (income taxes). Surely, the public records of earnings were inaccurate.

In the first century, Roman soldiers could either earn a pittance or be among the wealthiest of wage earners. Emperors enlisted tens of thousands of soldiers, commanders, and technicians every year as Rome expanded with unstoppable momentum. To be sure, military payrolls were a heavy burden on the state treasury. A legionarius, essentially a foot soldier, earned a measly 1 sesterce per month. Just how little pay was this? Trying to convert 1 sesterce at today’s purchasing power parity (PPP) is laden with difficulty. Luckily, the Romans had some sort of gold standard, since we could calculate how many sesterces a gold coin (aureus) was worth. If, say, gold is valued at a high average of $1,200 per troy ounce (actually worth $1,700 today, having gone up sharply during the COVID-19 crises), then a single sesterce coin was worth $3.25 at today’s conversion. Quoting GlobalSecurity.org:

Taking the modern value of gold at about $1000 an ounce, an aureus would be worth about $300, the silver denarius [25 to the aureus] worth about $12, and a sesterce [4 to the denarius] about $3. As of mid-2010, the price of gold was over $1200 per ounce, placing an aureus at about $325, the silver denarius at about $13, and a sesterce [at 4 denarii] $3.25.

In no way, could Roman soldiers live off $3.25 per month. Hence, they were massively incentivized to win battles and conquer new lands. In return for their excellent performance on the battlefield, they would be given generous additional large sums (“commissions”) via the distributions of the spoils and war. In addition, legionarii were given tax-free land grants at retirement in some of the empire’s most fertile regions, as well as food, drink, housing, and clothing during their entire duration of active duty. Their salary had other “paid in kind” examples. In fact, the word salary comes from sal (salt). Why? Lower-ranking officers had particular benefits, like receiving small bags of salt, essentially a day’s wages, in exchange for protecting roads leading to the Roman salt mines or accompanying salt caravans in rough provinces like Germania. The most talented and longer-term commanding officers, like centurions who managed troops of around 100 soldiers, didn’t have petty wages, work side jobs, or had incentivized compensation packages. They were simply very well paid, as much as 300 sesterces a month ($10,000).

The equivalent of today’s blue-collar salary was roughly 120 sesterces ($390) a month during the best of times. This was still not very much, so such earners did jobs on the side, just like many have to today, on nights and on weekends. Farmhands earned as much as 150 sesterces (roughly $500) a month, plus a portion of the harvest and often on-site housing.

Much better monthly patrician salaries were given to the educated and political elite and, thus, those following rarefied career paths: they might be specialized professors, tutors, or “coaches” of the imperial family (8,000 sesterces); physicians (30,000 sesterces); and pro-Consul provincial and colonial governors who earned massive incomes (82,000 sesterces) per month.

In terms of artisans and their SMEs, they often earned well (especially in cities). Naturally, we cannot speak of employee-like fixed salaries but rather of fluctuating profits. Small business owners, therefore, could have very attractive net incomes like that of pro-Consuls and medical doctors, especially if their technical skills were in high demand (like potters, jewelers, metalworkers, millers, and leather-makers) or contracted by the imperial administration. Since nearly all business records (kept on papyrus scrolls and wood tablets) are lost, we can only estimate a round sum of 1,000 sesterces (about $3,300) in profits per month in major cities like Roma, Londinium, and Neaopolis.

According to one classical historian, there were other well-paid professionals, especially in the performing arts, though not by today’s “Hollywood paychecks”:

[These] were artists, comedians, dancers and actors, who could earn between 80 and 150 sesterces a day [$8000/$14,500 monthly] plus food and travel expenses, having also the security of a number of annual performances. Of course, most reputable artists could get quite more.”

All in all, it was possible to make a very comfortable living in ancient Rome, though the vast majority of the populus Romanus was immensely poor.

Given what we have observed, there are some economic laws worth noting.

Firstly, the more qualified your individual talent and rarefied your trade, the more likely you will be compensated generously by the market and over long periods of time. In ancient Rome, an elite educator - a rhetor like today’s Ph.D. - was much better paid than modern professors. This was not because he was more skilled in academia, but because there were far fewer professional intellectuals 2,000 years ago than today. Today, doctorates are figuatively a dime a dozen. By contrast, we might say rhetores were worth "ten thousand" a dozen!

Another ironclad law of the market is that compensation tends to increase according to the adjusted cost of living (ACL) in urban and suburban settings. An ACL for a busy cobbler could be 100 sesterces a day in Pompeii, but as high as 200 in Roma, yet far less in agrarian Sicilia (Sicily) or outlying provinces like Dacia (Romania), where one might only net 20 sesterces a day. Above all, cobblers were more in demand where there was a lot of walking done each day, especially if servicing footsoldiers near military castra and city dwellers. Ergo, the law is not necessarily one of supply, but more of demand. This is what ultimately makes Roman cobbler’s earnings much higher or lower, respectively.

In conclusion, the wage gap in ancient Rome was enormous. It was more similar to modern rich-and-poor markets like Brazil and Argentina, where we find skyscraper financial districts a few blocks from shantytowns in Rio de Janeiro and Buenos Aires. The wage gaps and living standards were extreme, mainly because (as in today’s global South) the opportunities to advance were fewer and more precarious. There were suffocating taxes; festering corruption; organized crime; poor education; disconnected black markets; and greater levels of disease, misfortune, and extreme geography. Mountains, swamplands, volcanic and seismic regions could wipe out entire economies in a bad day. Remember what happened in Pompeii? That ancient city will be one of the protagonists in our next blog: Ancient Roman centers of commerce.