Not a day goes by when there’s not some concern raised about the state of the economy and how people are faring. While recent economic growth has been promising, wage growth is lackluster, many say. The middle class is shrinking. There’s too much income inequality, and the list goes on. These concerns are often compelling. Who wouldn’t like to see more opportunity and more growth? People yearn for the good life, to experience real human flourishing. Yet many in our society seem to be falling short.

Surely there must be something more that we as a society can do. Are there not public policies and programs, many ask, that, if structured and funded properly, could lead to the outcomes we seek? It’s a tempting vision and, for many, government intervention in the economy seems compassionate and fair. Yet this approach raises a number of questions. Do such public policies and programs actually work? More importantly, do they cohere with our traditional values of justice and charity?

Let’s assume that we have conclusive data that confirm an unfair or undesirable state of affairs exists. For example, wages are stagnating, the middle class is shrinking, or income inequality is growing. And let’s assume that we could allocate adequate funding and implement public policies or programs meant to rectify this situation over time. We could try to steer our economy or specific aspects of our society toward particular outcomes.

The idea has a certain appeal. But would it work? Would we have all the necessary information and know-how to socially engineer such results over time? And would we be able to do so without inadvertently causing indirect harm in some other way?

The issue is not new. The renowned twentieth-century economist F.A. Hayek, in his many writings, discussed in detail the intellectual hubris associated with such endeavors. In short, Hayek concluded, such undertakings would not work. To his point, there are many real world examples that seem to prove him right – including many of the shortcomings of the Great Society programs of the Sixties, not to mention the failings of more extreme versions of centralized planning, like communist regimes over the last century.

Moreover, Hayek would say, letting the economy grow through myriad voluntary market transactions, rather than through centrally designed public policies and programs, would lead to a “spontaneous order” that will generate more opportunities for more people over time. And there’s certainly much evidence in his favor.

Many understand and agree with the Hayekian perspective. They are not easily convinced of grand economic and social policy experiments, however well intentioned. Others are not deterred by Hayek or anyone else who raises similar concerns. For them, utilizing more public policies and programs to improve the status quo seems worthwhile and feasible.

These political debates continue with no apparent resolution in sight – not only in assessing the effectiveness of various policies but also in deciding upon the desired goals and objectives for such government initiatives in the first place. Should we focus on policies and programs that lead to more economic growth or ones that spread the benefits of such growth more equally throughout our society?

There’s another, even more important question to ask, however, one that relates to the first principles of our society. Are such endeavors just? Are such public policies and programs – aimed, for example, at improving wages, growing the middle class, reducing income inequality – consistent with our conception of justice?

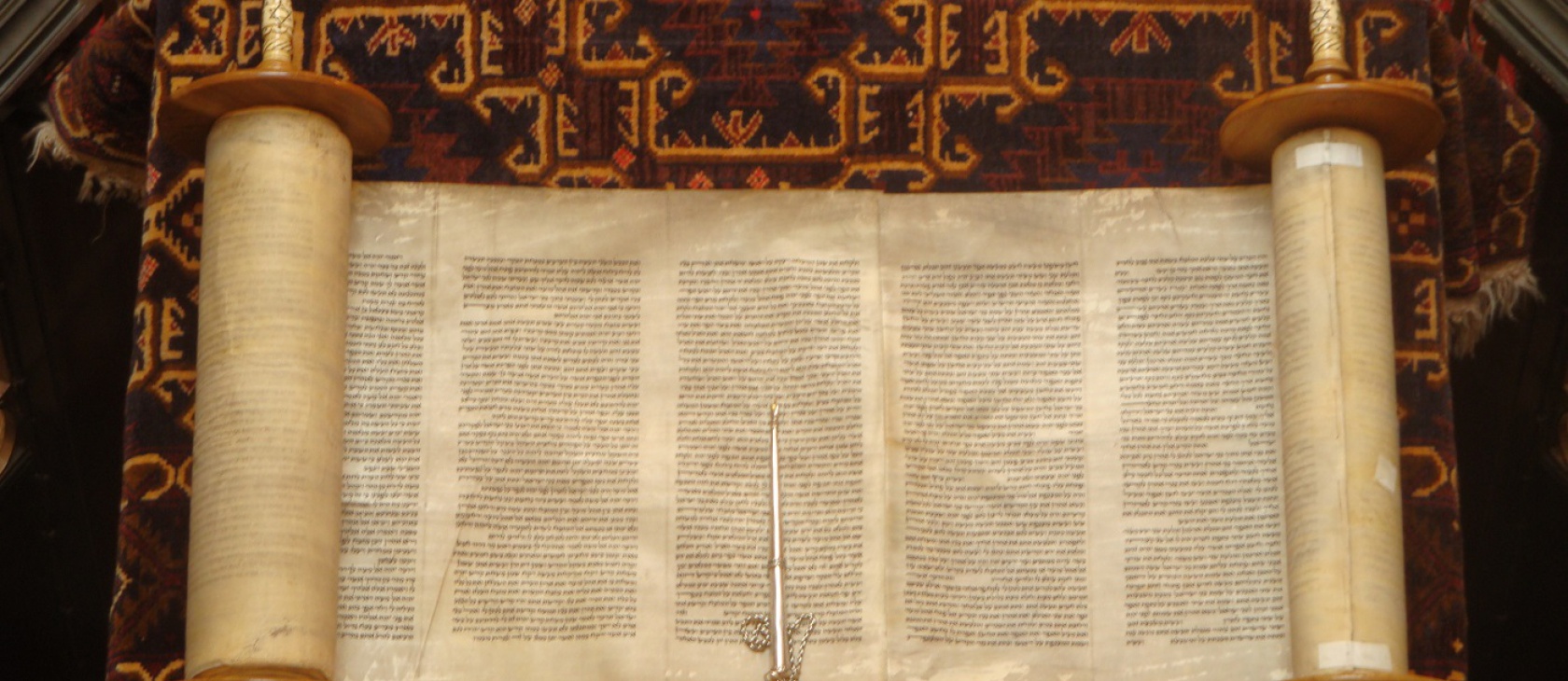

The traditional view of justice reflects first principles – principles which are inherent, if not explicit, in the Hebrew Bible.

For some, the answer is “yes.” These people subscribe to a broad conception of justice – sometimes called social justice, economic justice, or distributive justice. Under a type of Rawlsian calculus, economic disadvantages are seen as a function of some unfair state of affairs. Those deemed to be disadvantaged are accorded additional rights – rights to a better situation today and to a better economic future tomorrow – especially in a society as prosperous and affluent as ours.

Some might find this broad conception of justice to be compelling, but is it consistent with our traditional notion of justice?

The traditional view of justice reflects first principles – principles which are inherent, if not explicit, in the Hebrew Bible. They seem self-evident but are worth reiterating. There is right and wrong – with wrongs, like transgressions against another’s life or property, codified in law. We have free will. We are responsible and accountable for our individual actions and their consequences (excluding those beyond our control). In being held accountable, we are subject to receiving our just desert, with equality under the law favoring neither the poor nor the rich.

The principles seem straightforward, appealing to our common sense. They not only make sense but, for many, they are also godly. They reflect transcendent, eternal, universal, and moral values, as best as we can discern them.

Does the broad conception of justice – social justice, economic justice, distributive justice – cohere with the traditional notion of justice?

The broad conception of justice inevitably focuses on states of affairs, such as lackluster wage growth, a shrinking middle class, or growing income inequality, as distinct from individual actions for which one can be held accountable. In other words, states of affairs, not individual actions, are to be judged as just or unjust.

Yet, how exactly does one make such a judgment? “Do not steal” is a fairly straightforward concept of justice, rooted in a transcendent value – something eternal and universal – based on individual action for which one can be held accountable. Judging a state of affairs to be unjust is completely different. Exactly what level of wage growth is to be considered unjust? How small does the middle class have to get for it to be unjust? How much income inequality is unjust?

Some may look to economics or one of the other social sciences to discern if some state of affairs is unjust. But this betrays a misunderstanding. The social sciences can give us insights into many important economic and social factors and trends, and they can posit cause-and-effect relationships that may be helpful in understanding particular issues. However, they can never tell us what is unjust – which is a normative question, not a scientific one.

Without a clear concept of justice rooted in something transcendent, designating a particular state of affairs as unjust entails an arbitrary, and moving, target. More and more rights end up being propounded for more and more people. Will there ever be a time when income inequality in our society is not judged to be unjust?

The Bible implicitly assumes the primacy of economic liberty, of entrepreneurial freedom, of the free and voluntary exchange of products and services – subject, of course, to the laws of justice.

Most importantly, judging states of affairs to be unjust – and seeking legal remedies using the coercive power of government – will inevitably conflict with traditional notions of justice. For example, if there is a perception of too much income inequality, then the government will need to take from those with too much income, even when they themselves may have done nothing wrong. In effect, theft from the government – “legal plunder” in the words of the nineteenth-century French economist Frederic Bastiat – is being condoned in this instance as a form of justice, even though “do not steal” is one of the traditional cornerstones of justice. (This is not to deny the rationale for taxes to fund public services, including a basic social safety net.)

One might ask, “Is there nothing on justice in the Hebrew Bible that’s related to economic goals and outcomes?” Not really. There’s nothing on wage growth, nothing on the size of the middle class, nothing on income inequality. Rather, the Bible implicitly assumes the primacy of economic liberty, of entrepreneurial freedom, of the free and voluntary exchange of products and services – subject, of course, to the laws of justice. In this sense, our biblical tradition entails no broad consequentialist framework nor utilitarian calculations.

Some, in arguing for some form of distributive justice, cite Leviticus 25:10, where one is called upon, in the Jubilee Year (the fiftieth year following seven cycles of sabbatical years) to “return each man to his ancestral heritage” – i.e., to return the land to its original ancestral owners. The idea, some conclude, is to redistribute potentially unequal wealth.

This, however, does not appear to be an accurate interpretation. The obligation to return land had no legal significance. It simply reflected a religious obligation, with no effect on the rights of anyone’s private property, however unequally manifested in the community. It’s worth noting, as well, that the practice was likely never observed after the pre-exilic period.

One might also ask, “Is there no conception of the common good in the Hebrew Bible and all that that might entail?” Again, not really. The Bible is replete with promises of blessings, both spiritual and material, assuming one follows the commandments. And, for some, it embodies the hope of messianic times. But there is no specific conception of the common good, nor prescriptions for policy and law that could try to legislate for the common good.

Some find a rationale for the broad conception of justice within the modern interpretation of tikkun olam, sometimes translated as “repair of the world.” According to this view, not only must we mete out justice as traditionally conceived, but we must also do what we can to make the world a better place. For many, this includes creating more public policies and programs to help more people and to reduce inequalities – inevitably entailing more legal and financial obligations imposed on others by the government.

Judging states of affairs to be unjust – and seeking legal remedies using the coercive power of government – will inevitably conflict with traditional notions of justice.

However, while this modern version of tikkun olam may appeal to some, the traditional concept of tikkun olam is very different. The term is found in select parts of the Talmud, the ancient rabbinical commentaries on the Hebrew Bible and its interpretations. Typically translated as “for the benefit of society,” it is invoked to adjust particular laws in order to avoid certain perverse results. It’s in the Aleinu prayer, recited as part of the daily prayer service, but here it expresses the hope that the world will be perfected under the kingdom of God. It’s also found within Lurianic Kabbalah, but in this case the focus is on a spiritual mending of the cosmos, not on political solutions for the country or the world.

Still others try to find scriptural basis for the broad conception of justice. For example, in Deuteronomy 16:20, Moses says to the Israelites “Tzedek, tzedek, shall you pursue.” The word tzedek is sometimes translated as justice. The word tzedekah typically means charity. So, for some, charity is seen as a form of justice. It therefore entails, not just moral duties, but also legal obligations – ones that the government can impose on others.

Concern for those in need is undeniably laudatory. We as a society presumably could do much more to help those in need. And, some would argue, if we have to assume additional legal and financial obligations to make it happen, perhaps that is not only the charitable thing to do but also the just thing to do.

This link between justice and charity is questionable, though. Another translation for tzedek is “righteousness.” A tzaddik is a righteous person. Moreover, the Hebrew Bible, when referring to laws of justice, often uses a different word – mishpat – not tzedek.

It seems clear that justice and charity are two very different concepts in the Bible. As Israeli scholar Joseph Isaac Lifshitz clarifies in his book Judaism, Law & the Free Market: An Analysis:

Charity is considered an act of kindness rather than an act of justice. This means that charity does not redefine property rights. The rich man does not owe the needy, and the charity he gives is not a redistribution of his wealth according to justice.

This is not to minimize the importance of charity. The Hebrew Bible continually implores us to help the poor, along with the widow, the orphan, and the stranger. Moreover, within the tradition, there is a role to be played by the community – which, in earlier times, entailed charity collectors.

However, the community’s role is to be limited. The primary responsibility for charity is to be assumed by individuals and families. As Lifshitz notes, “It may be argued that a state should bear some responsibility and help the needy – but it is a responsibility that functions from the bottom up rather than from the top down. While the state does have particular welfare responsibilities, these should not supplant the primary responsibility that falls on the individual and families.”

Needless to say, doing charity well is often easier said than done. The great twelfth-century Jewish scholar Moses Maimonides devised eight levels of charity. The lowest level is when one gives unwillingly. The highest level is when one helps someone get back on his feet so that he will not be dependent on others in the future.

Justice and charity are undoubtedly core values which define what is good and right in our society, values which have led to enormous blessings over the years. However, justice and charity are often conflated, which runs the risk of distorting justice and undermining charity.

There can be no dispute about the fact that social and economic disparities abound throughout our society. However, within the traditional Jewish approach, these do not constitute issues of justice in and of themselves. They may suggest the need to be more charitable to the disadvantaged – depending on the situation – but this pertains to the moral obligation to be of help, not to the matter of justice.

As it says in the words from Micah 6:8, what are we obligated to do? “To do justice, to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God.”

(Photo credit: Lawrie Cate. This photo has been cropped. CC BY 2.0.)