Pope Francis has urged European political leaders to reduce government spending and lower taxes.

Well, he didn’t actually say that directly, but that is the unavoidable logic of his comments, although he might not understand enough economics to realise it.

“No peace without employment”

On March 24, 2017, European leaders gathered to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome that founded the European Union. They were addressed by the pope.

In this address, the pope repeatedly stressed the importance of the European Union working for the benefit of its citizens, to allow them the opportunity to find employment, financial improvement, and prosperity.

The European Union should not be a matter of grand politics and bureaucratic treaties; instead, said the pope, “Europe finds new hope when man is the centre and the heart of her institutions.”

He approvingly quoted the address of Paul-Henri Spaak, the former Prime Minister of Belgium and one of the founding fathers of the European Union, on the signing of the Treaty of Rome. In 1957, he described the goal of the European Union as “the material prosperity of our peoples, the expansion of our economies … new industrial and commercial possibilities.”

Pope Francis has, probably inadvertently, made the moral case for tax cuts.

And Pope Francis made it clear that he was not talking about mere spiritual development, or a vague movement towards international amity, but of a practical, material development. What is needed in Europe, he said, is:

the pursuit of peace and development … There is no peace without employment and the prospect of earning a dignified wage.

Youth unemployment - the European failure

Employment, the dignity of work, and the need for jobs to help people provide for a family was a theme that ran through the pope’s speech. And no wonder; with unemployment rates of 20 percent or more in Greece and Spain and more than 10 percent in France, Italy and Portugal, unemployment is the scandal that the European Union tries to ignore.

And those figures, dreadful as they are, mask an even bigger problem. Because most European Union countries have rigid employment laws, those in jobs are often protected even when those jobs are no longer economic. But that means that the full force of this economic failure falls upon those who are not working, particularly young people who complete their education, looking for their first jobs, only to find that there are none to be found.

It is youth unemployment that shows the failure of the European Union’s policies.

Across the EU, roughly 20 percent – one in five – people under the age of 25 are out of work. If that were not disgraceful enough, many countries are far worse than that average; 2016 saw more than 50 percent youth unemployment in Greece, 45 percent in Spain, more than 30 percent in Italy, almost 25 percent in France. Even Luxembourg, at the heart of the European project, saw more than 20 percent of its young people unable to find a job. And Sweden, supposedly so egalitarian and socially well-adjusted, was nearly as bad.

It was surely these shocking statistics, and the harrowing human stories behind them, that Pope Francis had in mind when he reminded the European Union’s leaders that:

Europe finds new hope when she is open to the future – when she is open to young people, offering them serious prospects for education and real possibilities for entering the work force.

In many European countries, those prospects are anything but promising.

Practical examples of success

Even if the European Union’s leaders could be forced to acknowledge this huge economic and social problem, the question remains: What is the solution?

The answer is certainly not job creation schemes. They rarely lead to sustainable jobs. (If a job is uneconomic that it needs to be propped up by a government subsidy, it will only survive while the subsidy lasts.) Worse, they tax profitable businesses to raise money to prop up lame ducks, and so risk destroying successful employers.

Unemployment is the scandal that the European Union tries to ignore.

But the advantage of the European Union is that we have 28 countries in the same economic area, subject to roughly the same external pressures, but all pursuing slightly different policies. That lets us see what works best.

Overwhelmingly, what does work in job creation is low taxes.

The chart below shows how successful the various European Union members were at creating jobs during the period from 2000 to 2008. The horizontal axis shows government spending as a percentage of GDP – which, in the long run affects taxation rates – while the vertical axis shows each country’s success in creating jobs in that eight-year period.

The result is painfully clear; those countries on the left of the chart, with lower taxes, were far more successful at creating jobs. Those on the right, with higher taxes, failed their citizens and left millions of young people unable to start their careers.

There seems to be a cut-off at around 42 percent; those countries that kept their governments’ spending below that level were successful at creating jobs; those who didn’t were not.

That was, of course, before the financial crash. And while some people will accept that low taxes are beneficial in good times, many want the protection of government-issued money when disaster strikes, and many European Union countries adopted a Keynsian approach of increasing government spending in order to boost the economy.

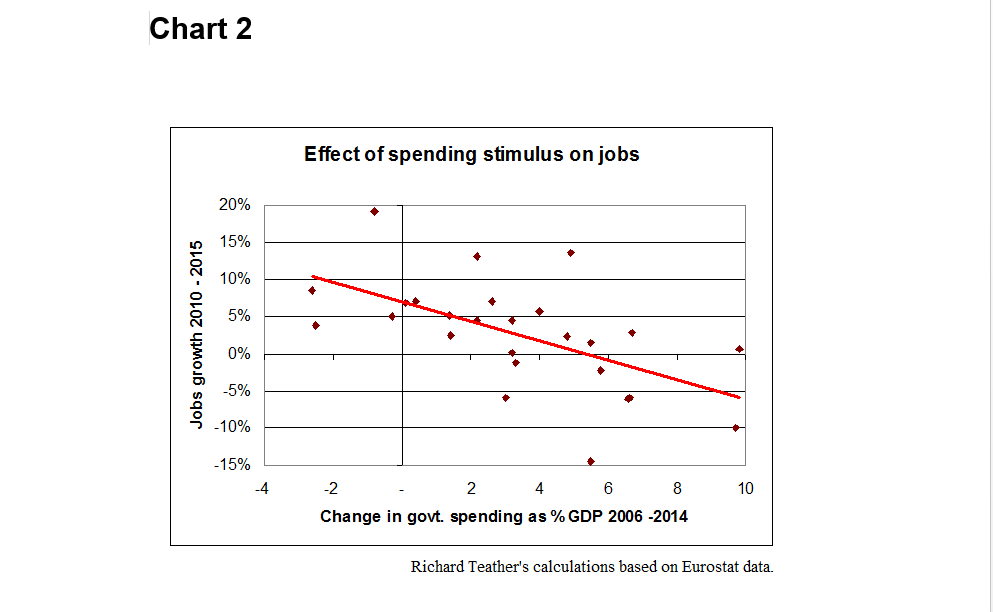

But was it a success? The chart below suggests that it was not. The horizontal axis shows how much governments increased their spending after the financial crash (2006 compared to 2014), while the vertical axis again shows how successful these countries were at creating jobs, this time over the five-year, post-crash period from 2010 to 2015.

Although there is a little more variability, which is not surprising in a period of great financial instability, the overall result is reasonably clear. Those European Union countries on the left side of the chart, that kept their government spending under control – by either reducing it or allowing it to increase by no more than about 2.5 percent – generally saw reasonably successful jobs growth of five percent or more during the post-crash period. Those countries that had significant increases in government spending in response to the crash saw little or no job growth.

Indeed, the exceptions support the general rule; the only two countries that had decent job growth despite a significant increase in government spending were Ireland and Estonia, both of which started from relatively low, pre-crash levels of taxation.

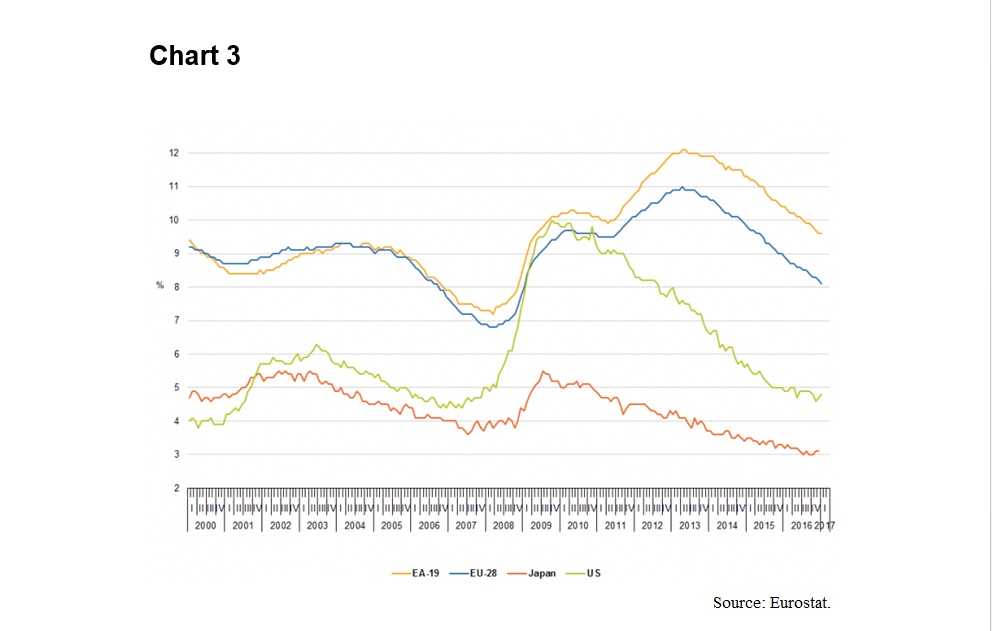

Even the European Union’s own charts show this problem. The chart below, produced by the EU’s statistics division, compares unemployment levels in the European Union countries against those in the United States and Japan. The top two lines are the EU (depending on whether “new” or “old” members are included, but the two lines are very similar); the line in the middle is the USA; and the one at the bottom is Japan.

A few things stand out from this.

First, unemployment levels in the European Union are significantly higher than in the USA and Japan. That difference is a sign of how much the politicians’ policies within the EU are failing its citizens.

Second, yes, many countries around the world suffered in the financial crash; indeed the U.S. unemployment rate briefly rose to EU levels in 2009. But whereas unemployment in the USA and Japan (both of whose governments spend less than usual European levels) has largely fallen back to pre-crash levels or below, in most of the European Union the recovery has still not yet happened.

Third, the European Union saw a second increase in unemployment between 2011 and 2013, at a time when both the USA and Japan were creating jobs and getting their unemployment levels back down again. That was a consequence of both the lack of economic resilience before the crash – with the economies strained by high levels of government spending – and the failure of its governments’ post-crash policies. And as we saw above in Chart 2, it was those EU governments that had big increases in their spending in response to the financial crisis that damaged their people’s employment prospects the most.

Correlation or causation?

The evidence seems clear. Pope Francis wants European Union governments to introduce pro-growth policies, to improve employment prospects for all (particularly the young), and the way to do that is to reduce taxation and government spending.

But do the statistics reflect a causal relationship? Is there really a link between low government spending and higher job creation?

Indeed there is, and the evidence is merely proving what most economists have said for decades: Taxes discourage us. If the government taxes something, there will be less of it. We know that taxes on smoking or environmental pollution are enacted specifically on that basis. Why should we be surprised when the same thing is true of business and jobs?

There are large examples and small ones: a multinational that decides against opening a large factory in Europe, because the after-tax returns are not enough to justify the investment and the risk; the small business that decides not to take on a couple of extra members of staff, because the tax would mean that the profits were not high enough to justify the extra hassle of employment; etc.

A few years ago I was talking to a British Treasury official who complained that self-employed people work hard until they make about £60,000 ($74,640 U.S.) for the year but then, he said, they stop working and play golf instead. Well, of course they do. At around that point, their income tax rate jumps from 20 percent to 40 percent, and they probably have to register for VAT, which means a further 20 percent in tax and more paperwork. No wonder many decide that the after-tax reward is not worth the effort.

The moral case for tax cuts

Pope Francis has, perhaps inadvertently, made the moral case for tax cuts.

He is right that European Union governments should have aim to expand opportunity for all, so that everyone has the chance to lift himself out of poverty and provide for a family. Their failure to do so, the massive unemployment and even higher youth unemployment that have blighted much of Europe, is a scandal that deserves more attention.

But what the pope may not realise is that the best way governments can do this is to get out of the way, to cut public spending, reduce taxes, and allow the economy to flourish. This is not just theory; the evidence of the last couple of decades shows clearly the lower-taxed countries in Europe are far more successful at generating the economic growth and the jobs the pope knows that people need.

(Photo credit: Edgar Jiménez. This photo has been cropped. CC BY-SA 2.0.)