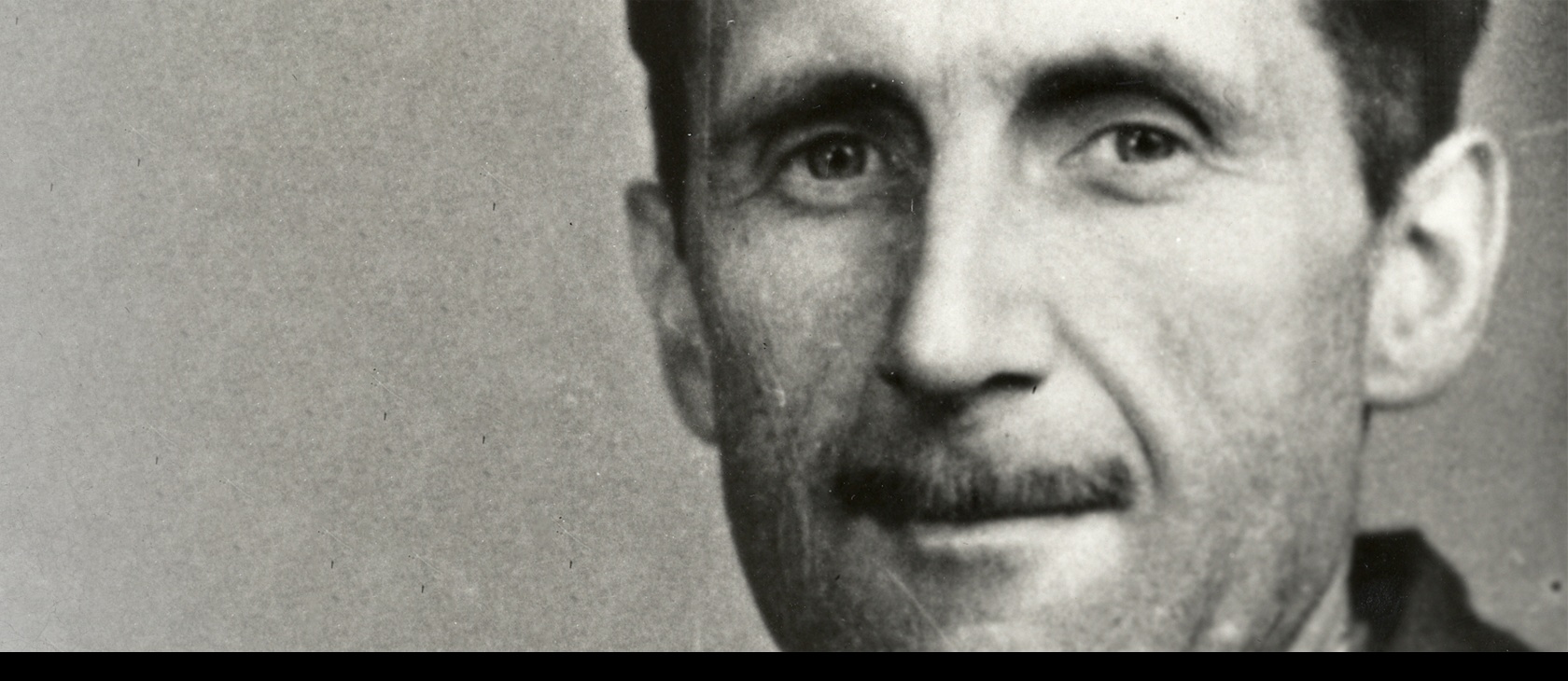

The culture war between George Orwell and the left is soon to enter its tenth decade, and the newest salvo has just been launched. In a Financial Times (FT) article entitled “How George Orwell Became a Dead Metaphor,” Naoise Dolan bemoans the legions of “Orwell fans” who overpraise Orwell and reduce him to a “dead metaphor” like those he disparaged in “Politics and the English Language.” Of course, Orwell is not innocent here, Dolan adds, but has invited the recurrent waves of “Orwellmania” since his death.

The Hundred Years’ War between George Orwell and his intellectual enemies continues unabated. Dismissed by another generation as a “dead metaphor,” Orwell’s name and work are occasions for fracas and feuding—and an endless succession of quotes.

The sharp shift in focus—from Orwell’s purported sins to the alleged hollow-drum sycophancy of his readers—may be new. But the language of derision and dismissal from the left is tiresomely familiar.

The animus, which was mutual, has now endured decades since Orwell has gone to the grave. Yes, Orwell came increasingly to hate the left during his lifetime. In turn, the left—from the top down, starting with the chairman of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), Harry Pollitt—has long hated him. This history of the fast-approaching “Hundred Years’ War” between Orwell and the Marxist left possesses seven stages, three of them posthumous. The FT article by Dolan represents the opening round of the emergent seventh phase. Its new angle of assault focuses more on “Orwell’s fans”—exempting the members of the Orwell Society, may we hope? —than on Orwell himself.

Each phase during Orwell’s lifetime of this never-ending siege was closely associated with a major landmark in Orwell’s publishing and reception history; in his afterlife, the landmarks of the fifth and sixth stages were mainly linked not to what Orwell said but rather what other writers—fans or foes—said about him. This panoramic historiography encompasses far more than the Two-Minute Hate of a few ephemeral, if belligerent, exchanges. Nor even an extended Hate Week confined to an intemperate spat about a book or two, or about a position on a historical event (say, the Spanish Civil War or World War II), eventually blowing over and forgotten. Instead, from the late 1930s to the late 1940s, the anti-romance of “Orwell and the left” became a “Hate Decade”—and it winds its way through new minefields into our own time, well on its way to becoming a full century of hate.

It warrants emphasis that the collocation “Orwell and the left” refers specifically to the Stalinist left of Orwell’s day, and since that time to the Marxist left and some feminist radicals. This is the so-called far left, near synonymous in Orwell’s lifetime with Soviet communism in general and the CPGB in particular. The distinction between “left” and “Marxist/Stalinist left” should be underlined, for the vast majority of left-of-center readers have found Orwell’s work valuable and compelling, however flawed or limited they nevertheless judged it. Rather, it is the ideologically committed “far left” whose vituperations against Orwell are the stuff of the never-ending Hate Week.

As John Rossi wrote 40 years ago, “In itself this would seem something of a paradox, for after all, Orwell was a committed socialist, a one-time member of the radical Independent Labor Party, and a supporter of the post-war Labour government”—and, I might add, a personal acquaintance and former close colleague of one of its most influential and politically radical cabinet members, Aneurin Bevan.

Yet none of that has really mattered to the Marxist and feminist left. Although most mainstream socialists and other radicals outside the Stalinist orbit welcomed Orwell no later than the late 1940s, with the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four in 1949 and Orwell’s death seven months later, the Stalinist left never did. First under the sway of the Popular Front in the 1930s and then the CPGB during World War II and for a time thereafter, the left has rejected him as the major cultural threat challenging their contention that the “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics” was not a cruel misnomer, indeed that it was anything but state capitalism—or rather “oligarchical collectivism.” And, of course, a threat to their increasingly suspect claims that they themselves represented “English socialism”—and not Ingsoc.

Let us briefly review this history, devoting most attention to a recent example of the latest and seventh stage of invective.

Orwell's breakup with the Stalinist left began, one could say, before they had even dated.

- 1. Of Name-Calling and Nose-Tweaking: The Road to Wigan Pier (1937)

Orwell’s breakup with the Stalinist left began, one could say, before they had ever even dated. Orwell had never been a member of the CPGB, had never been a communist in any sense—and so was not a “renegade” and had no remorse about lacerating and lampooning English socialists. The hate fest began with the publication of The Road to Wigan Pier in 1937, following his two-month research trip to the Midlands, and some of Orwell’s best salvoes and funniest barbs are to be found there. Harry Pollitt of the CPGB reviewed the book himself in The Daily Worker, accusing Orwell of “slumming” and bourgeois “snobbery,” while also suggesting that it was Orwell’s own belief that “the working classes smell.” To Pollitt and others, Orwell himself was the Diabolus. As the author of Wigan Pier had half-anticipated, lost in all the cheek-pinching and defensive retorts was the simple fact that he himself was a (rather cranky) socialist advocate who was poking fun at his own side.

From this “high point” in Orwell’s relationship with the British left, relations spiraled steadily downhill, and the next three stages went beyond name-calling and standoffish interaction to unconcealed contempt.

- 2. Spain and the Communists’ “Betrayal of the Left”: Homage to Catalonia (1938)

Orwell left for Spain four months before Wigan Pier’s publication, determined to fight at the front. He wound up in Catalonia, having signed on with a mixed anarchist-Trotskyist militia, known as the POUM (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista—United Marxist Workers’ Party). His second phase of relations with the left emerged from his seven months in Spain. His experience there intensified his animus and expanded its range far beyond the British left to “the stupid cult of Russia” and Stalin’s machinations throughout Europe and the world—and specifically Stalin’s intention, despite all the pious rhetoric about a united Popular Front of leftists against fascism—to eliminate all non-Stalinist representatives of socialism, including Orwell himself and many of his POUM comrades. Orwell’s anguish over the lost war, his dear comrades, and the POUM’s ruthless suppression by its putative allies (the Soviet advisers and the Spanish Communist Party) received full expression in Homage to Catalonia (1938), his elegiac memoir that reflected Orwell’s upsurge in bitterness and belligerence toward British Stalinists as well as his broader targets. Soviet NKVD files available after the USSR’s dissolution in December 1991 establish that the Russian secret police spied on him in Spain and may have targeted him for elimination.

- 3. Of Patriotism and Pig Rule: Animal Farm (1945)

Orwell’s abhorrence of the Soviet Union and the Stalinist left in England incubated during the next several years, confirmed by the August 1939 signing of the Nazi-Soviet Pact. Meanwhile The New Statesman and other Stalinist organs were busy condemning Orwell in no uncertain terms. Orwell’s loathing for the USSR did not substantially change despite the wartime alliance that followed in the wake of Hitler’s double-cross of Stalin and invasion of the USSR in June 1941. Wartime ally or not, Russia was a brutal tyranny, and Stalin nothing less than “a disgusting murderer.”

By wartime’s close, a third stage of relations—which represented a far bigger downward step than ever before—was at hand. The process of antagonism that had commenced with Wigan Pier, and which had dramatically expanded beyond the English scene during the Spanish Civil War and Homage to Catalonia’s appearance, now reached a new intensity. “I consider the willingness to criticize Russia and Stalin as the test of intellectual honesty,” he told John Middleton Murry in August 1944. In Animal Farm, which was accumulating rejection after rejection that summer and fall, he put himself to the test—and passed with flying colors.

The headlines alone from communist publications during the next four years tell the story of Orwell’s official standing in CPGB circles: “The Nightmare Mr. Orwell,” “Prisoner of Hatred,” and—my own personal favorite— “Maggot of the Month.”

- 4. Faceoff on the World Stage: Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

Although Orwell was sick during much of 1947–48, he felt driven to complete the writing of Nineteen Eighty-Four, which marked the confrontational high point between the left and the author whom Pravda would soon headline an “Enemy of Mankind.” With Nineteen Eighty-Four’s publication in June 1949, both Orwell’s strategic range and satirical renown widened still further. He soon passed from being the left’s most visible and most effective foe in Britain to being the leading cultural Cold Warrior in the postwar West. Henceforth the showdown between “Orwell and the left” would play out on the world stage, having fully intertwined with the higher-order Cold War dynamics of America vs. Russia, capitalism vs. communism, the so-called “Free” World” vs. “the Iron Curtain.” The novel’s catchwords and Newspeak idiom would soon be inextricably bound up in the agitprop between East and West, and Nineteen Eighty-Four itself would become the most famous work of Cold War literature ever published.

By the time of Orwell’s death in January 1950, the CPGB and the left had adopted a strategy that has persisted to this day: a mix of literary derogation, political diatribe, and psychoanalytic autopsy (of Orwell’s “sick,” “counter-revolutionary” mind).

- 5. The BBC Adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954)

BBC teleplay productions of Nineteen Eighty-Four were broadcast (twice) in mid-December 1954 and proved the decisive rocket boost that catapulted both Orwell and his novel into the starry heavens of still-enduring canonical enshrinement and international fame. “The ‘Orwellian’ Night of December 12,” as I once titled a recounting of the extraordinary and still little-acknowledged impact of those incredible two hours (8:35 p.m. to 10:35 p.m.) that Sunday evening, is the identifiable date when “Orwell” and his proper adjective achieved public fame.

For the size of the audience—which one scholar claims was the largest ever except for Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation the previous year—shot his novel into the realm of supersellerdom (from 150 to 19,000 copies per week within days) and soon established his catchwords as fixtures in the international political lexicon and cultural imagination. The effect was meteoric: By the time the second broadcast had ended, on Thursday night, December 16, the language and vision of Orwell’s novel had gone “viral.” “The term ‘Big Brother,’ which the day before yesterday meant nothing to 99 percent of the population,” editorialized The Times of London days later, “has become a household phrase.”

Coinciding within days of Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s ignominious fall from power after his official censure by the Senate in December 1954, the BBC-TV broadcast marks the fifth moment in the pugnacious 70-year history of Orwell vs. the left. In 1955, Isaac Deutscher’s “reply” to the posthumous Orwell—which of course was not to Orwell or his novel but to the BBC teleplays—turned Orwell and Nineteen Eighty-Four into an atomic culture bomb, a veritable thermonuclear threat against humankind. Wallowing in “boundless despair,” Orwell unleashed on the world “an ideological superweapon” that portended the numerical nightmare of 1-9-8-4.

Nineteen Eighty-Four would become the most famous work of Cold War literature ever published.

6. The Anti-Orwell Intellectual Brigade on Parade (1960–2024)

Beginning with E.P. Thompson’s essay “Outside the Whale” in 1960, a New Left critique emerged: Orwell the detached, cynical inner émigré. Decrying the conservative political climate in Britain throughout much of the 1950s, Thompson blamed it on Orwell, making the preposterous claim that a single essay, “Inside the Whale” (1940), had “led an entire generation” to embrace a posture of despair about the possibility of social change. According to Thompson, Orwell’s Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four also made fashionable a generation’s stance of resigned acceptance of totalitarianism and a refusal of political commitment. Thompson treated some admiring comments Orwell made about Henry Miller in “Inside the Whale”—where he defended Miller’s choice to stand as an observer rather than become an activist—as Orwell’s ruling, lifelong beliefs, thereby ignoring the fact that they were written during a brief, prewar phase of his thinking as a pacifist.

A legion of other similarly minded critics and intellectuals hostile to Orwell followed as the 1960s and ’70s unfolded, among them Raymond Williams and Edward Said. Throughout the Cold War and into the present century, Orwell’s leftist critics have had nothing comparable to Orwell’s writings to wield, either in English or any other language, as we have noted. Bereft of any works of the imagination even remotely equal to Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, communist dialecticians have been reduced to the desperate measure of flinging Orwell’s own coinages back at him and his supporters—as well as trying to hang them on numerous Western leaders and agencies—for example, “Big Brother Reagan,” “Big Sister Thatcher,” the “Hoover Thought Police,” “the Orwellian language” of “liberal bourgeois Newspeak,” and on and on. Such phrases resounded in screaming headlines in the state-controlled Party newspapers of Eastern Europe and the USSR—even as Orwell’s books were officially proscribed and unavailable in either libraries or bookstores, all of it further illustrating the ironies of impotence. Yes, George Orwell had gone down the memory hole in the communist world—yet millions of citizens recognized both his neologisms and even his name in adjectival form.

- 7. “Hero” Orwell: “The Dead Metaphor” and “His Groupies” (2024–)

As I remarked at the outset, having exhausted their energies by fruitless direct assaults on Orwell, the most recent strategy is to open fire on the amorphous, unnamed “Orwell crowd.” Naoise Dolan’s critique of Orwell in FT clues us in as to the current thinking of the youngest generation of what I term “the new new left.” Titled “How George Orwell Became a Dead Metaphor,” Dolan has a ready answer: It is thanks to “the Orwell fans” who “want their hero to step in and put things right,” “evok[ing] the great man’s foresight about the dangers of an overweening nanny state, a censorious far-left or whatever else may be getting your goat that day,” ranging from Israel and Palestine to cancel culture and Ukraine.

As it turns out, however, apart from targeting the “acolytes,” the newest stage is not so new. Dolan is simply channeling Thompson through the work of Edward Said—whether or not she is aware of the fact. “Above all, his fans,” says Dolan of Orwell, “admire the idea that it might be possible to take a courageous stance precisely by refusing to take a side at all.” Notably, “most of Orwell’s acolytes are English”—which presumably accounts for their irresistible attraction to Orwell’s clever construction of a “nexus between Englishness, rational thinking and truth.” Quoted at length by Dolan is Edward Said’s attempted takedown of Orwell in 1980, “Tourism Among the Dogs,” in The New Statesman, where he echoed and updated Thompson, arguing that “a new generation” was equally mesmerized by Orwell. It, too, lamented Said, was seduced into Orwell’s “mendaciously” “stakeless bystanderism” and Orwell’s lionizing of “Englishness” and “fair play.” These are all attitudes or values championed by right-wingers who “identify with Orwell in part because he invites them to.” We can blame Orwell, therefore, for his admirers.

Dolan agrees that today’s “Orwell fans” and “groupies” have acted on his invitation, though she largely keeps her guns aimed on them and their groupthink, not him. As a vocal advocate for queerness, LGBTQ+ rights, and inclusivity, she speaks for a new leftist generation that abhors homophobia, ableist language, and societal ignorance about autism. (Orwell’s own alleged homophobia goes unmentioned.) She also inveighs against Orwell’s “naïve” allegiance to “spartan language”—as if it “could unmask stupidity.”

Throughout the Cold War and into the 21st century, the far left has had nothing comparable to Orwell's writings to wield.

Ironically, or perhaps predictably, the one name that is mentioned among the “groupies” is a (conveniently dead) writer who has long been a whipping boy for the bien-pensant left: Christopher Hitchens. Her ultimate aim turns out to be the unmasking of the groupies’ stupidity for following this Pied Piper. His “unfettered appreciation,” indeed “veneration,” of Orwell turns out to be the wellspring of “the Orwell mania.” The ritualistic quoting all began, Dolan naively maintains, with Why Orwell Matters (2002). Alas! However serviceable it would be to blame the left’s most recent bête noire, Hitchens, such quoting began more than a half-century earlier, as I have documented in a half-dozen studies of Orwell’s reputation. Nonetheless, Dolan proceeds: “Hagiographies like the one Hitchens wrote” are the secret source of what has resulted in “Orwell” becoming a “dead metaphor.” We are supposed to imagine that Hitchens’s purported overpraise has paved the way for the raves of today’s nameless “Orwell groupies,” for whom “it might not be too much to say that Orwell invented the bra and engineered the fall of the Berlin Wall.” Stefan Collini, a veiled Orwell hater who recently dismissed my own work, branded Hitchens as Orwell’s reactionary heir, whose similar plain-man persona spewed “‘no bulls--t’ bulls--t.”

In the end, therefore, Naoise Dolan has distilled the Orwell “crowd” to Hitchens. Orwell “the dead metaphor” apparently doesn’t matter—precisely because Hitchens still does. A pernicious influence on the “Orwell groupies,” Hitchens has been “the worst sort of wingman”—or better: (right-)wingman. Their “mania” was ignited by his mania.

Writing in 1971, the Welsh socialist author Raymond Williams smugly prophesied that Orwell’s “influence” on the radical left was “diminishing” and would continue to decline. Williams’s forecast about the left’s lessening “engagement” with Orwell has proved false, however, as the assault on the author has not just proceeded into our century but even intensified. But why?

Granted, Orwell is big game. He is, in fact, the very biggest, one of the most important social commentators who has ever lived if measured in terms of the effluence of his influence. No other writer is so endlessly cited and quoted to buttress an argument or establish intellectual pedigree. After all, Nineteen Eighty-Four is the most influential (and bestselling) political work of all time: No other book has ever risen five (!) times to No. 1 on the international bestseller lists—a feat it performed as recently as 2017, 68 years after its original date of publication.

Given its arsenal of battle-certified coinages, Nineteen Eighty-Four has provided an arsenal of satirical salvoes during political controversies and culture wars for more than seven decades. For instance, a stage adaptation of the novel was performed on Broadway in 2022, intended as a biting critique of the first Trump administration. Meanwhile, numerous voices on the right have viewed speech codes, cancel culture, mandatory adoption of preferred pronouns, and left-inspired infringements on personal liberties as eerily resembling Orwellian forms of creeping totalitarianism.

Yet, as Williams also acknowledged, Orwell still stands as “an enormous statue warning you to go back.” Hence the need to destroy the reputation of a political writer of world stature, the only one who commands respect across the entire span of the ideological spectrum, from right to left—with the sole exception, that is, of the far left. To “take him down”—as the Marxist and feminist left have long sought—is to remove the roadblock to their perceived advance. It remains, therefore, a prime directive.

Moreover, throughout the Cold War and into the 21st century, the far left has had nothing comparable to Orwell’s writings to wield, either in English or any other language. Bereft of any works of the creative spirit even remotely equal to Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, Marxist dialecticians have been reduced to the desperate measure of vilifying his admirers and ironically flinging Orwell’s own coinages back at him and his supporters. Conor Cruise O’Brien—another left-wing detractor—spoke the truth when he compared Orwell’s chastening impact on Marxist intellectuals with that of Voltaire’s on the 18th-century French nobility: “He weakened their belief in their own ideology, made them ashamed of their clichés, left them intellectually more scrupulous and defenceless.”

May his chastening impact continue to prevail.