In his new book, The Kingdom of God and the Common Good: Orthodox Christian Social Thought, Dylan Pahman, research fellow at the Acton Institute and executive editor of the Journal of Markets and Morality, presents a groundbreaking study of Orthodox social thought, highlighting commonalities with and differences from other Christian denominations in this area. The book offers a clear, well-researched guide to church history, tracing the practice of Orthodox social teaching over millennia, gleaning insights along the way from the law, the prophets, wisdom literature, and the Gospels, always with an Orthodox emphasis on reading scripture not alone but with the church.

Eastern Orthodoxy is often thought of as inward-looking and rarely engaged in public policy debates. Yet its rich history and sacramental theology have much to offer in seeking the common good.

By Dylan Pahman

(Ancient Faith Publishing, 2025)

Most interestingly, Orthodox Christian Social Thought integrates Orthodox social thought with political economy, emphasizing not just economic efficiency but also virtuous institutions that foster neighborly love and productive service in God’s Kingdom. In so doing, Pahman explores a historical theology of care for the poor, Christian witness, the role of work and innovation, and biblical views of the common good, covering commercial, political, and social relations and their application within the Orthodox tradition more specifically.

In Orthodox social thought, it is the church that binds the world and the Kingdom of God, and Orthodox Christians have a long history of confronting both poverty and economic growth and the riches it affords, political oppression, exile, and religious wars. In so doing, Orthodox social thought has had to wrestle with public welfare, productive and unproductive labor, price fluctuations, interest, money lending, and population growth.

Pahman’s work presents this history clearly, showing how the church fathers and scripture-based teachings help us learn from the past and shape Orthodox social thought in the present, offering a framework for navigating political and economic life without being too precisely prescriptive. We learn from Christian Rome and Byzantium about justice and mercy toward the poor; from the so-called Dark Ages about the entrepreneurial spirit of the monasteries; and the true nature of symphonia, that ideal harmony between church and empire, and what happens when that is corrupted. Throughout we find bright lights of innovation, ascetic witness, and kenotic love, especially in medieval Rus’.

All this is deeply rooted in liturgical theology, where the worship of the church shaped its vision of society and of human dignity, and continues to do so today, beginning with the most pivotal event in human history: the Incarnation.

There is a saying that history is the conscience of the social sciences. Building on this insight, Pahman transitions from a historical survey of theology to an analysis of political economy. You might wonder what economics has to do with, say, the creeds? More than you might think. Man lives neither by spiritual nor by physical bread alone.

Pahman’s treatment of political economy begins with the great economist Lionel Robbins, who offers this definition: “Economics is the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses.” Economics is necessary because we live in a world of material scarcity and are limited by our fallen nature. Moreover, economics is a social science, and we are social, made in the image and likeness of a triune God. We have infinite dignity, yet we are also finite and broken. As such, we respond to incentives, and so institutions and rules of the game matter.

In other words, political economy goes beyond technical cost benefit analysis: We must also understand the norms that emerge from culture: our habits, government, laws, and religious commitments. Again, institutions matter, and they govern (with a small g) our behavior. Consequently, Orthodox social thought can inform how we think about institutions and whether they advance or detract from the common good in the light of the gospel. In fact, Pahman begins his book with a question: “If the Kingdom of God is truly at hand, what does it mean to live as a subject of that Kingdom?” The literature is vast on the theological and political differences among Christians attempting to provide an answer. Yet getting this right is essential, and for Pahman it’s a matter of attaining true social justice.

So what is the practical application of Orthodox social thought in fostering the common good? Economists are quick to point out that you should be careful what you agitate for—you might get it. Being ethically minded about policy isn’t enough; we cannot merely intend to do good; we must generate good outcomes. This is true for two important reasons: policy is about people and so should first do no harm, and scarcity demands that we direct our limited resources in the most productive manner possible.

In Orthodox social thought, it is the church that binds the world and the Kingdom of God.

In attempting his thoroughly Orthodox answer to the question of living as subjects of God’s Kingdom, Pahman takes us on a star-studded journey through the history of political economy: from the Late Scholastics and the moral philosopher-turned-father of modern economics Adam Smith to John Maynard Keynes, Wilhelm Röpke, Kenneth Boulding, and F.A. Hayek. For many, the social science of economics means socialism. But we can’t properly evaluate socialism as an economic system without addressing ethics in addition to efficacy of central planning. Virtue must always ground our approach to the economy, with a focus on human dignity. After all, there were Christian socialists who believed that modern industrial progress alienated the working class, which needed government protection through state economic planning. But does socialism understand what it means to be fully human?

Orthodox Christian Social Thought highlights commonalities with Catholics and the Reformed Protestant traditions. For example, Pahman begins his journey into a holistic Orthodox social thought in the book of Genesis, as do these other traditions. A properly understood human anthropology—where did we come from and what is our true end?—is essential to understanding all forms of social formation. Orthodoxy also recognizes that the focus when speaking of “the common good” should always be on Jesus and his life. Despite our status as exiles, strangers in a strange land, we are still called to seek the good of the city (Jeremiah 29:7) in community.

Unlike some individualistic approaches to biblical theology, the Orthodox tradition calls for reading scripture with the church, not alone or outside it. This is how best to understand God’s design and desire for His Kingdom, as well as our role in constructing “previews” of this Kingdom here and now. In reading the church fathers on wealth and poverty we learn that, while wealth is not evil, the human heart can be. We should reject a false dualism that pits wealth against poverty, but must always be wary of what riches can do to our hearts. Pahman argues that while wealth can help us “see” the Kingdom, it can also blind us, so discussions of wealth and commerce must always be approached with a Christ-centered heart. Pahman notes that we live in the richest time in human history, making a proper theology of wealth and poverty more critical than ever.

While there are commonalities with other Christian traditions in addressing economics, Pahman elaborates on four key Orthodox emphases that stand out in its social teaching. These include asceticism, salvific grace, the relationship between church and state, and the concepts of kenoticism and sobornost.

Asceticism may not seem like a particularly social practice, yet for the Orthodox it’s a means of fostering true communion with God, and thus contributing to the common good. Spiritual disciplines like almsgiving, fasting, praying, confession, silence, and, for some, even celibacy are not just personal but inherently social. For example, fasting means that you can offer the food you would have eaten to the hungry. The early church described in the book of Acts banded together to share all property in common to care for one another. This is not a prohibition of private property but an act of love and sacrifice for the sake of Christ that allows us to bear witness to His love in the world.

What may prove startling to, say, Protestant readers is how Orthodox teaching blurs the distinction between common grace and particular grace. Pahman argues that all grace is potentially salvific and, to some extent, sacramental because it reveals God to us and provides an example of how we can and should extend grace to others. It is a model for neighborly love. Pahman argues that the unique Orthodox contribution lies in demonstrating how we are more than stewards of God’s earthly gifts but also “priests” in the world.

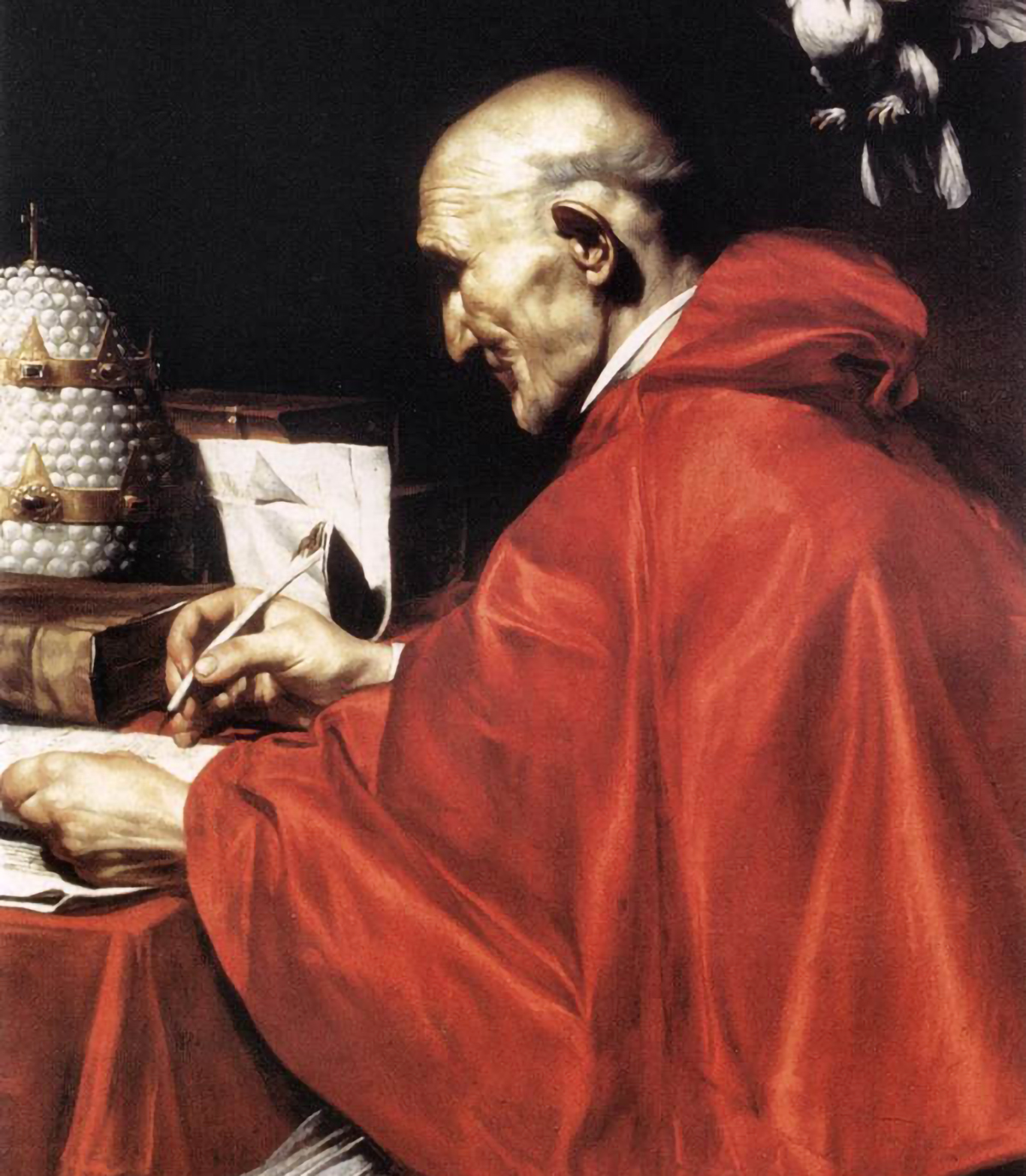

Pahman’s historical approach shows how often the earliest Christians were exiles or minorities and had to figure out how to care for one another under harsh conditions. Finally, it was St. Gregory, a monk who became pope in 590, who paved the way for the church in pursuing its distinct missional role through extensive social work. He understood this work as that of “service rather than power,” both in light of the Incarnation and Christians’ often powerlessness in the face of hostile empires.

On the flip side, distortions of symphonia, or the harmony between the church and the civil realm, result when church and state are too intertwined. The church makes its unique and essential contributions to the common good when it is free from political vassalage. Thus, religious freedom is essential. In fact, political privilege can be dangerous, creating “winners” and “losers,” especially in the economy. Natural law provides a model for civil law adjudicated by the government and informed by justice without falling into radical religious nationalism.

A brilliant example of Orthodox social teaching on church-state relations is the humanism that arose within the Byzantine Empire (4th–15th centuries) at a time when the church was free to articulate its missional role in society and worked to shape the moral foundations of public life. Rooted in the doctrine of the Incarnation, orthodoxy views culture as capable of sanctification, something that can be transformed and offered to God rather than merely rejected as “worldly.”

We should reject a false dualism that pits wealth against poverty, but must always be wary of what riches can do to our hearts.

Lastly, Orthodox social thought provides two concepts for how to live in community. Kenoticism means identifying oneself with the lowest members of society, and in doing so caring for the less fortunate in a relational manner. Sobornost is a concept that recognizes the spiritual unity of all and urges harmony and communion. We are not merely individuals but exist as one in the Body of Christ. Both kenoticism and sobornost offer an egalitarian perspective on the social order and neighborly love. The church exists “for the life of the world” (John 6:51) as a sacramental presence. Pahman urges us to consider the “cosmic weight of the Incarnation as ‘ministry of reconciliation’ (2 Cor. 5:18).”

The Kingdom of God and the Common Good fills an essential gap in the literature on Christian social teaching, providing a rich and accessible historical account of 2,000 years of reflection on the role of the church in the world. While Orthodox social thought has long existed and been practiced, it has long been undertheorized. No longer. Pahman’s survey of political economy from an Eastern perspective provides an excellent primer from which any Christian can benefit.

Today’s economies and governments look vastly different than those experienced by the early Christians. Understanding the church’s response to wealth and poverty today means also understanding how it has responded in the past and discerning its unifying, transcendent wholeness in meeting modern needs. As Pahman reminds us, the Kingdom of God is “within us” (Luke 17:21), “at hand” (Matthew 3:2), and yet to come (Matthew 6:10). He even suggests that urban monasteries could enhance our ascetic service and witness. Moreover, we need a moral political economy grounded in the common good for God’s glory, and this book offers that for any Christian. Pahman’s work invites all Christians to reconsider how theology, economics, and social life converge in the pursuit of the Kingdom of God.