The story is most often told that religion is that force of coercion that attempts to bend the mind to its own perception of truth and resists, by its very nature, any institutional and most especially legal attempts to ensure the right of people to seek truth on their own.

In his recent book Liberty in the Things of God: The Christian Origins of Religious Liberty, Robert Louis Wilken sums up this portrayal of history in this way:

Religious freedom is often thought to be the work of the Enlightenment. In the sixteenth century, so the story goes, when the Reformation took hold in Europe, confessional differences led to the suppression and persecution of Christians by Christians. … A half century of bloody conflict, the so-called wars of religion, was set in motion. But by the middle of the seventeenth century men with great wisdom and less religious fervor came on the scene, and the fanaticism of religious believers gave way to the cool reason of the philosophers. Armed with notions of the superiority of reason over faith, skeptical of received truth, and distrustful of religious claims and institutions, these enlightened thinkers forged a new set of ideas about toleration and religious freedom. Through their efforts the modern idea of liberty of conscience was born.

New challenges to human flourishing demand new definitions, vocabulary, and guidance. The Catholic Church has always understood this. It could not speak to the present moment otherwise.

The remainder of Wilken’s work is an exploration and repudiation of that simplistic thesis. Wilken brings together an illuminating history of Christian thinkers and how their reflections developed over the ages. He suggests that significant writers within the first centuries of the Church, while not developing a full, systematic, and mature doctrine of religious liberty and tolerance, nonetheless drew on the knowledge of classical philosophy, Scripture, and the experience of Christians at the hands of the Roman state—a state that, after all, had executed their founder—to formulate arguments against their persecutors.

To see the complexity of the historical breadth of Christian debate over the distinctions between the state’s coercive power and the equally compelling yet persuasive authority of the Church, we can look at what is arguably the foundational text that sets up this debate over religious liberty, the words of Jesus in Matthew 22:21: “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”

Throughout the ages, even once Christians had emerged from being a persecuted minority to becoming, at times, a persecuting establishment, these words of Christ were never forgotten, and often grappled with in vastly different ways.

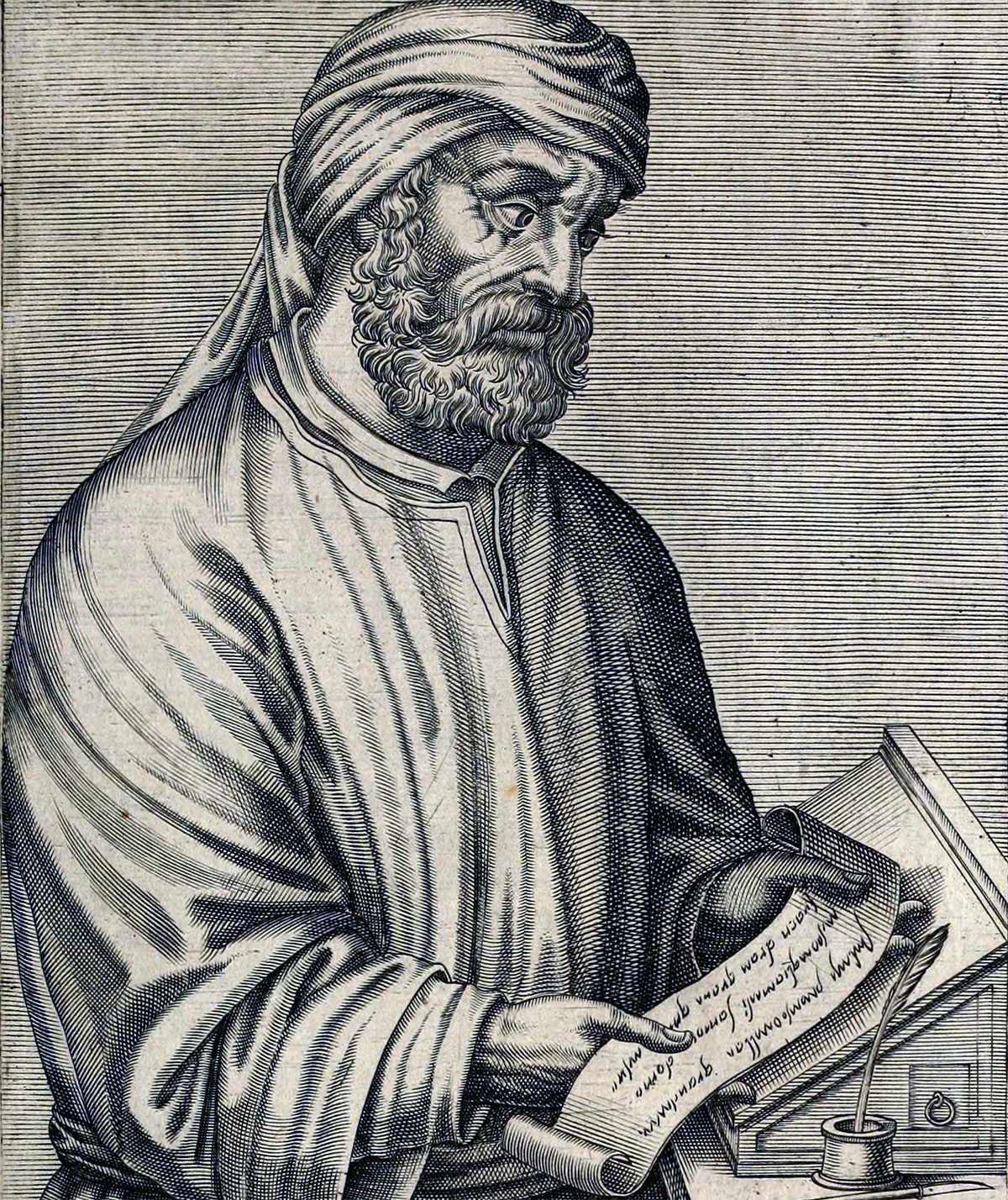

For example, we find in the third century a theologian from Carthage, Tertullian, sounding almost modern, credited with first employing the phrase “religious liberty” in his argument for tolerance:

See that you do not end up fostering irreligion by taking away freedom of religion [libertas religionis] and forbid free choice with respect to divine matters, so that I am not allowed to worship what I wish, but am forced to worship what I do not wish. Not even a human being would like to be honored unwillingly. (Wilken, p. 11)

He further pleads,

It is only just and a privilege inherent in human nature that every person should be able to worship according to his own convictions; the religious practice of one person neither harms nor helps another. It is not part of religion to coerce religious practice, for it is only by choice not coercion that we should be led to religion. (Italics added)

In the next century, the noted Latinist Lactantius would likewise articulate his defense for tolerance, saying, “Let words be used rather than blows, that the decision may be free.”

Tertullian’s and Lactantius’s are only the beginning of an extended argument through almost two millennia of Christian thought about religious freedom and the state. Over the centuries, thinkers would come at the question from differing vantage points, ranging from Augustine and Aquinas to Calvin, Luther, and others. Such reasoning was retrieved and deployed at the time of the Protestant Reformation. It was also in this period that Erasmus cites Jerome’s and Chrysostom’s commentaries on the wheat and the tares to say that Christ forbade the execution of heretics.

This and similar ideas expressed at different points throughout the Church’s history provide a rich backdrop for reflection on the development of the idea of religious liberty within the framework of the Church’s tradition.

Development of doctrine, as St. Vincent of Lérins and St. John Henry Newman help us to understand, is to be expected as part of the Church’s role in teasing out from the seeds of the deposit of the Faith the implications of what was first entrusted to the Apostles.

It might be said that Newman wrote his way into the Catholic Church in penning his Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine (1845), wherein he outlines the dynamic nature of the Church’s own probing of her beliefs from the implicit to the explicit, delineating the numerous stages and qualifications required. In an introductory essay for Development, the late Fr. Stanley Jaki noted that for Newman “there is no suspended animation” in doctrine. While consistency and continuity are constitutive components of her teaching, there emerges, under the pressure of innumerable contingencies, deeper implications and articulations of the Faith that might not have been as manifest or defined in one setting as they might come to be in another.

The very compilation of the canon of the New Testament took a three-centuries-long process of sifting through various letters of St. Paul, the memoirs of the Apostles, and a host of materials in circulation in the first centuries, this in order to distinguish the authentic texts from pious works and doctrinally heterodox ones. The most significant instance of the development of Christian doctrine was a deepening understanding of the divinity of Jesus Christ himself.

There is no need here to go into the nuances of the argumentation between the homoousios versus the homoiousios clauses. We need only note that the process of development allowed the Church to confront questions that arose regarding her relationship to Christ only once the precision of Greek and Latin grammar, vocabulary, and categories, for example, were brought to bear on such questions.

The most significant instance of the development of Christian doctrine was a deepening understanding of the divinity of Jesus Christ himself.

Even if not as primary to Christian theology as its understanding of the Godhead, the matter of the Christian life lived out in the world gives rise to considerations of conscience, tolerance, and liberty and can be seen in nascent form in the Scriptures and those thinkers alluded to previously. There we detect a seed in need of cultivation and development.

The process of unfolding these nascent ideas yields still more questions, such as the relationship of conscience to the integrity and protection of truth. The role of reason in coming to an apprehension of truth and the necessity of freedom for the proper exercise of that reason must be considered. Then there is the critical question of whether authentic faith can be coerced.

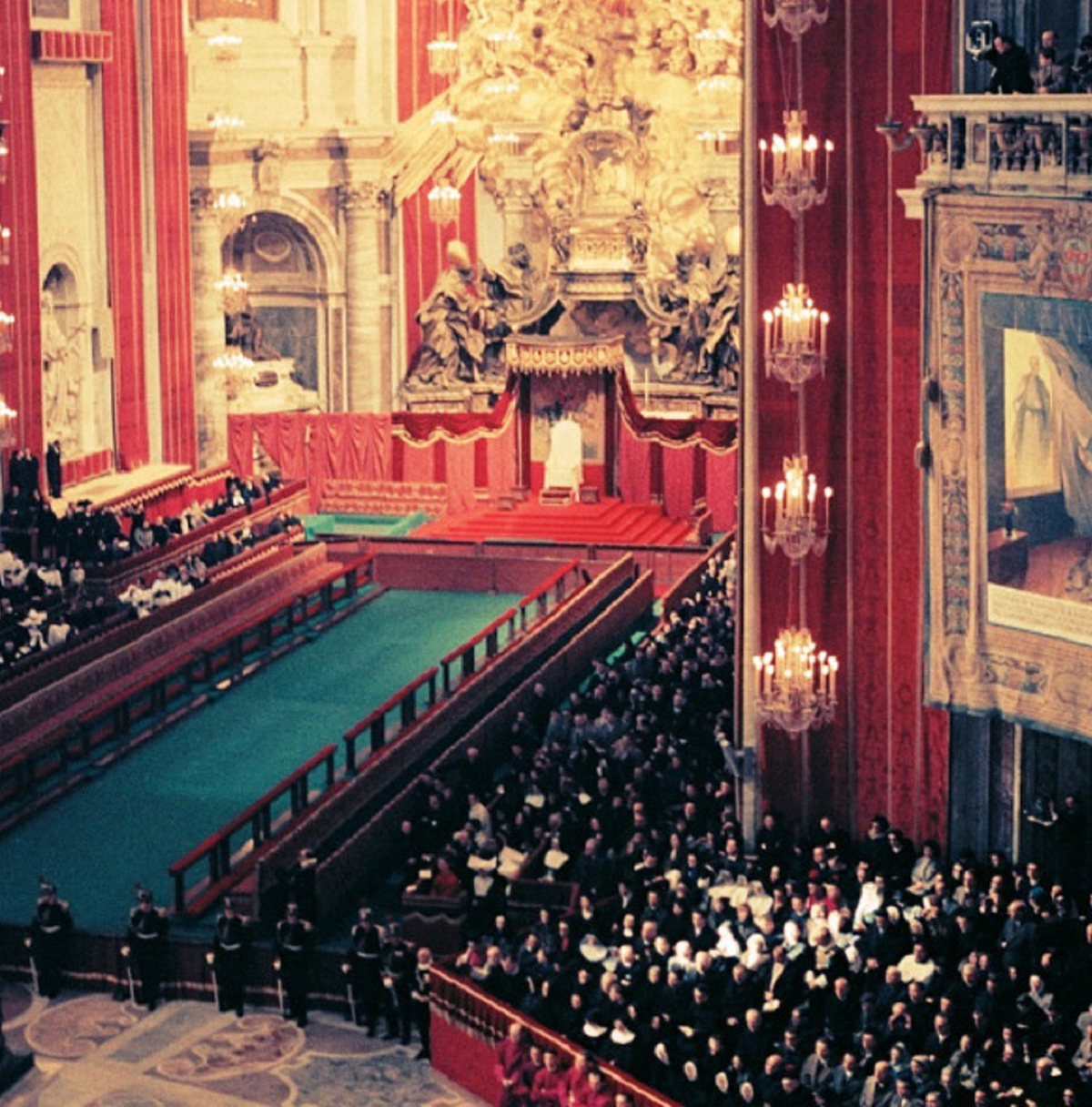

In terms of the Catholic magisterium, a significant culmination and development of these ideas emerged at the Second Vatican Council. Much of the public debate subsequent to the council related to the liturgical life and practice of the Church, as well as to the moral, specifically sexual norms governing the life of the faithful. Yet even today, Dignitatis Humanae (DH) provokes significant discussion inside and outside the Church given its argument pertaining to the right of personal religious freedom and the role of the government in relation to that freedom.

The political and historical context in which the Church has to function informs our understanding of the refinement of her teaching. These contexts range from extreme and hostile secularism to atheism, communism, and socialism, materialism and National Socialism. Each context raises new reference points requiring reformulated arguments, vocabulary, and the appropriation of new discoveries or insights in order to re-present the perennial content of the Faith. What might have been an adequate and effective reply under one set of circumstances in a particular historical moment or a particular place might prove incomplete or inadequate in another.

The late Cardinal Avery Dulles, SJ, a prominent American ecclesiologist, did a more than adequate job in outlining the theological reasons why DH may rightly be seen as an authentic development of the Church’s teaching in matters of conscience and the proper limits to state power. His argument prescinds from a parallel argument over whether previous Church teaching on the matter of religious liberty was indeed infallible teaching or only doctrina catholica, i.e., nondefinitive, nonbinding teaching.

In acknowledging the importance of the question, Dulles’s argument points to the intention of the Council Fathers in drafting DH as well as that expressed within the document itself, which is to maintain the continuity between the prior teaching of the popes in relation to religious freedom, both personal (i.e., in relation to conscience) and social (having to do with the role of the state). Indeed, Pope St. John XXIII said as much in his inaugural address opening the proceedings: “The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of the faith is one thing, and the way in which it is presented is another.”

The importance of the debate, Dulles underscores, relates not only to the objection advanced by Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre and the “conservative” opposition to DH that the document breaks continuity with previous popes, specifically those of the mid-19th century, but also to the more “progressive” elements who saw in the development of the prior teaching by a council of the Church an opportunity for the Church to repudiate settled moral doctrines such as artificial contraception.

Building on Newman, Dulles shows that while matters of a social or political character do “not follow exactly the same course of development as pure dogma” due to their need to take into account different social contingencies, their “fundamental principles are constant.”

Dulles sees DH as seeking to develop the Church’s teaching in light of the changed social, political, and ecumenical reality of the Church in the mid-20th century, which found the Faith under a different series of threats than those in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the later context, the Church was threatened by various militant secular liberal movements, whereas in the earlier she found herself confronting varieties of socialist, fascist, and communist governments.

Dulles also sees a theological shift from the neo-Scholastic focus on ontology to a more personalist approach emphasizing human dignity and freedom under the influence of Archbishop Karol Wojtyła and others. This, Dulles says, places DH in the broader “framework of a comprehensive theory of human freedom based on classical theology and contemporary personalist insights.”

Throughout history, one notes a recurrent response by some religious institutions to the secular world: to create some form of theocratic arrangement, holding to the idea that as God is the one, supreme creator and sustainer of all that is, and is himself the source of all authority, he alone can be the sole ruling authority on earth as well, extending his reign throughout society by means of civic legislation.

Dulles identifies a prescient insight from St. John Paul’s pontificate, which augments DH in his repudiation of integralism as the Church’s preferred option concerning relations between the civil and ecclesiastical spheres. The pope said that “religious integralism, which makes no distinction between the proper spheres of faith and civil life, which is still practiced in other parts of the world, seems to be incompatible with the very spirit of Europe, as it has been shaped by the Christian message” (“Discorso di Giovanni Paolo II Durante la visita al Parlamento Europeo,” October 11, 1988).

The idea of integralism is essentially what stood in the way of the Church’s development of its understanding of religious liberty. If the Church holds definitively to a basic amalgamation of the state and her own authority, then religious liberty, in the sense that people should be free to pursue religious truth unburdened by state coercion, is impossible. Integralism’s insistence on what effectively amounts to a confessional state fails to grapple with the tensions that a host of Christian thinkers have debated over the centuries. Thus, integralism can end up supporting the persecution, not merely the anathematization, of heretics.

The idea of integralism is essentially what stood in the way of the Church’s development of its understanding of religious liberty.

In their essay “On Integralism, Religious Liberty, and the Authority of the Church: 19th Century Popes and 20th Century Popes Disagreed,” Professors Lawrence King and Robert T. Miller provide us with a range of solid sources on this, including Cyprian, Lactantius, Ambrose, and Aquinas, as well as numerous ecumenical councils and canonical sources to the effect that, in various ways, the Church ought to shun the use of state coercion in proclaiming her message.

Informed by such history, DH instead develops church teaching on a free society without leaving the public sphere “naked” of moral or spiritual impulses. Aware of the need for society to have a moral orientation that all can know through natural law, DH amplifies the implications of previously established church teaching on human dignity and the insights of Christian anthropology as seen in the idea of the inviolability of conscience that underscores the essential nature of consent to the practice of virtue. In its reiteration of the council’s teaching in DH, The Catechism of the Catholic Church offers this summation:

The right to religious liberty is neither a moral license to adhere to error, nor a supposed right to error, but rather a natural right of the human person to civil liberty, i.e., immunity, within just limits, from external constraint in religious matters by political authorities. This natural right ought to be acknowledged in the juridical order of society in such a way that it constitutes a civil right. (CCC 2108)

Many of the same insights into anthropology, conscience, and the requirement for volition for virtue that allowed for the Church’s development of her understanding of religious liberty might have application as well to economic liberty. Any authentic development of Catholic teaching in this area must presume continuity of teaching with the past, but also involves reflection upon the growing knowledge uncovered by economics and other social sciences. While economics is generally not as closely related to the core of Church teaching on topics such as family and marriage, neither is it radically divorced from moral obligation.

Pope St. John Paul II’s encyclical Centesimus Annus (CA) offers the most thorough “re-reading” of Catholic social thinking in the aftermath of the collapse of history’s most extensive experiment with socialism: the Soviet Union and socialist systems in Central Europe. One central question John Paul sought to examine was the extent to which the business economy might throw favorable and “practical light on a truth about the person which Christianity has constantly affirmed” (CA, no. 32).

Within this rereading, the pope affirms both the practical and moral legitimacy of profit, entrepreneurship, rational self-interest, productivity, and a stable currency, as well as the importance of the role of private property and its social dimension, while distinguishing consumerism from the business economy. He elaborates the traditional principle of subsidiarity to demonstrate the priority of nonstate action on behalf of those in difficulty. Higher levels of state intervention are justified only in a temporary “substitute function,” and he warns against “bureaucratic ways of thinking,” concluding “that needs are best understood and satisfied by people who are closest to them and who act as neighbors to those in need” (see CA, nos. 32, 42, 43, 44, and 48).

Centesimus Annus opened a new dialogue on human freedom and its implications, and in this sense stands besideDignitatis Humanae as representative of the Church’s developing insights and practical moral implications of liberty.

The present historical moment confronts us with a profound and ominous confusion related to such fundamental matters as the very definition of human life and person, sexuality, and identity. From that incomprehension, and derived from it, there emerges additional and complex confusion surrounding man’s role in the care of creation. This inevitability entails questions of human freedom and intelligence as it relates to a rightly formed conscience as well as to the role of freedom in the endeavor to make use of natural resources for the common good and the material betterment of mankind.

Pope St. John Paul II elaborates the traditional principle of subsidiarity to demonstrate the priority of nonstate action on behalf of those in difficulty.

The Church has the experience of two millennia to bring to bear upon the historically unprecedented rise out of poverty of so many millions over the past two centuries. The causes of this prosperity are many and interrelated. A deepened understanding of that prosperity is indispensable to human liberty and the extension of that liberty to the expanded capacity of people to exchange goods and services—and because of that, knowledge—on a global scale.

It would be a failure of epic proportions were the Church not to live up to her responsibility here. Throughout human history, the fundamental economic question people have had to confront has been how to organize their use of scarce resources for human survival. Today a new question arises that necessitates our confrontation not with scarcity but with abundance. How to live lives worthy of human dignity amid such prosperity is a question the Church is well-suited to help us confront, but only if she continues to develop her insights in the areas pondered in this presentation.

(This essay has been adapted from a speech delivered at the Newman and Controversies in Catholicism conference, held in Rome on December 5, 2019, and sponsored by the Acton Institute.)