It is a curious thing when an artist, thinker, or writer gains influence outside the audience he intends or is comfortable with. When a thinker associated with the right becomes popular on the left, or a novelist associated with the progressive left becomes popular among conservative readers, there can be a sort of strain felt between the audience in fact and the “true” audience, or between those who feel themselves to be the authentic recipients of a work’s message and meaning and those who, to the true believers, come across as opportunistic in their enjoyment of works in tension with their own views. The same is true when a writer working within an academic discipline gets picked up by those outside it: Those working within that discipline may find the co-opting of these thinkers misplaced at best or malicious at worst.

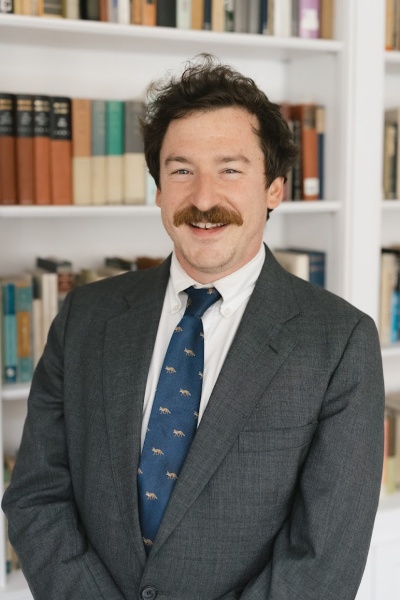

Friend or foe of liberalism? Conservatism? The intellectual trajectory of this influential thinker has left many fighting for his legacy—perhaps mistakenly.

Such is perhaps the case with Alasdair MacIntyre, whose intellectual trajectory carried him from an early Marxism to a later Aristotelianism and finally into a form of Catholic Thomism. Along the way, speaking in and to those traditions, MacIntyre’s work was championed by each and picked up by others, and has now spilled out in its reception far beyond the walls of academic philosophy departments. MacIntyre’s influence is often marked on those associated with types of “conservatism” today, who count themselves critics of liberalism and work to understand its failings. That “influence,” however, is by no means uncontroversial, particularly in light of MacIntyre’s own direct disavowal of “conservatism” and refusal to engage with the so-called Benedict Option advanced by Rod Dreher, one of his prominent popular receptors.

In assessing MacIntyre’s legacy briefly here, I will avoid restating at length the high points and summaries of his writing that have been offered of late in the wake of his recent death. Instead, I start with his development as a thinker across time, which I take to be a model of intellectual virtue in the life of the mind. I then consider his influence on those outside his discipline and conclude with a reflection on philosophical biography more broadly.

In 1959, as a philosopher just entering his 30s, MacIntyre published a profound moral reflection in The New Reasoner titled “Notes from the Moral Wilderness.” The New Reasoner was a short-lived journal for communist dissidents, founded by those disaffected with the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary, as well as those grappling with the revelations occasioned by Khrushchev’s 1956 “Secret Speech” titled “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences.” Amid a mounting tide of evidence that Stalinist Russia was guilty of abhorrent crimes before, during, and after the Second World War, morally sensitive communists often became internal critics of their own tradition or else, as many did, became what MacIntyre called “ex-Communist[s] turned moral critic[s] of Communism.”

In “Notes,” MacIntyre outlines the difficult position of the moral critics of communism, standing as they often do within the liberal tradition that often acts as a “kind of photographic negative of Stalinism.” Where the Stalinist “horizon of morality” is identical to “the course of history,” such that “the Stalinist identifies what is morally right with what is actually going to be the outcome of history,” the liberal moralist “puts himself outside history as a spectator. He invokes his principles as valid independently of the course of historical events.”

In MacIntyre’s account, liberal moralists have simply arbitrarily accepted a different moral system, not justified it. In other words, those sympathetic to Stalinism need merely ask, “Why do the moral standards by which Stalinism is found wanting have authority over us?” to render liberal criticisms relatively ineffective, or at least to put the ball of ethical justification back in the court of the liberal moralist.

The problem with both approaches that MacIntyre identifies is that they are presented as a false dilemma, or at least that apart from these two options there is a third path: “What has to be done positively is to show that there is a third moral position,” one that does not fall “into the dogmatic ossifications of Stalinism” nor “the arbitrariness of liberal morality.” That is, a defensible ethical approach must not simply affirm that whatever happens in history is good in the abstract but must also show that it is justifiable. In short, a third moral option must “provide us with some conception of a basis of our moral standards.”

For all their acknowledged failings, Marxists preserve, MacIntyre argues, a “concept of human nature, a concept which has to be at the center of any moral theory.” Unwilling as yet to discard Marxism itself, MacIntyre appeals to this idea of human nature as the means of self-criticism that would reject what he calls the “crude utilitarianism” of Stalinism. A similar argument was later advanced by Canadian political philosopher George Parkin Grant in his Lament for a Nation, originally published in 1965. Liberalism, Grant argues, presents no coherent account of human nature and thus lacks a moral core that could provide a limit to supposed “progress” in politics and technology. Marxism, for its part, at least maintains a conception of human good against which supposed “progress” must be compared. This conception of human good is the life raft for the moral core of Marxism in MacIntyre’s early writing, which he hopes keeps it from necessarily descending into the Stalinist error.

If MacIntyre’s early work introduces, for his liberal readers, some troubling questions about the moral status of Marxism in his thought, it also sets the stage for his own intellectual and moral development. In seeking a different path from both Stalinism and liberal theory, MacIntyre arrives at the tradition of virtue, first exemplified and expounded in the works of Aristotle and given new life and application in the Middle Ages through the work of philosopher-theologians like St. Thomas Aquinas. This tradition suggests there is something about how human beings are that gives us useful information about what is good for life as a human being. By studying a thing according to its nature, Aristotle and those who follow him wager, we can learn about what that thing is for and thus what would make that thing good. This tradition is both meaningfully in contact with reality and justifiable, satisfying the conditions outlined in his earlier “Notes.”

It is tempting, however, for MacIntyre’s ostensible followers and critics to see in his virtue ethics a kind of nostalgia. When, in After Virtue, MacIntyre proclaims boldly that we must choose between Nietzsche and Aristotle, those raised on worldview curricula and disaffected with the course of modernity instinctively know whom to choose. But in his prologue to the third edition of that same book, MacIntyre disavows a nostalgic approach to the past and a “careless misreading” of his work that would lead someone to this conclusion. He writes,

Because I understand the tradition of the virtues to have arisen within and to have been first adequately articulated in the Greek, especially the Athenian polis, and because I have stressed the ways in which that tradition flourished in the European middle ages, I have been accused of nostalgia and of idealizing the past. But there is, I think, not a trace of this in the text [of After Virtue]. What there is is an insistence on our need to learn from some aspects of the past, by understanding our contemporary selves and our contemporary moral relationships in the light afforded by a tradition that enables us to overcome the constraints on such self-knowledge that modernity, especially advanced modernity, imposes.

What is needed is not simply to sit down and memorize the Aristotelian corpus without modification. MacIntyre’s approach to philosophy understands the Aristotelian and Thomistic tradition, among other traditions, to be methods of moral “enquiry” rather than a rote accumulation of abstract dogma. Viewing ethics in this way forecloses both nostalgia and projects of naive recovery, despite the accusations of critics to the contrary. In embracing the virtue tradition, MacIntyre did not himself, nor teach others to, pick up and parrot Aristotle as a Bible, nor take any later development of virtue ethics as a copy-and-paste script for ethical living. He instead introduced the possibility of within-tradition refinement, an activity which all his receptors can take up.

Many of MacIntyre’s admirers come from fields outside his own; his influence is marked on social and political commentators, political theorists, and perhaps surprisingly those who study business management. The varied receptions of MacIntyre’s work have been given expansive treatment in Learning from MacIntyre, a 2020 book edited by Ron Beadle and Geoff Moore. Beadle and Moore are themselves professors of business ethics, and MacIntyre’s influence on their work on virtue in the workplace and in business management has been strong. In their editorial introduction, they state that their purpose for the creation of the volume was for contributors to explain MacIntyre’s influence within their own discipline, assembling a delightful representative sample of the types of thinkers on whom MacIntyre has left a significant mark, from Frankfurt School critical theorists to Catholic social thought apologists and beyond.

In addition, interested readers will find in Christopher Stephen Lutz’s “Alasdair MacIntyre: An Intellectual Biography” a description of MacIntyre’s own intellectual movements as read through the stages of his scholarship, as well as moments of profound and enviable intellectual charity. Early in his career, Lutz explains, MacIntyre published an essay entitled “The Logical Status of Religious Belief,” where he presented what Lutz calls “a summary statement of MacIntyre’s fideistic philosophy of religion.” The essay was criticized by atheist philosopher Antony Flew and Christian theologian Basil Mitchell contemporaneous to its publication in 1957. When “Logical Status” was republished in 1970, Lutz wrote, “MacIntyre added a new preface in which he thanks Flew and Mitchell, along with his colleague Hepburn, for their criticism, and rejected the essay’s ‘irrationalism as both false and dangerous.’” MacIntyre, it seems, faced critics who changed his mind and was happy to acknowledge their contributions.

If MacIntyre could sometimes take well the criticisms of his own work, those whom MacIntyre criticizes could certainly emulate and exercise the same charity. Among the readers of MacIntyre throughout his career have been other critics of liberalism who, MacIntyre complained, took him somehow to be on their “side” in ongoing debates. Again, in the prologue to the third edition of After Virtue, MacIntyre suggests he has been taken up as an ally to the “communitarians” in the academic debate between the communitarians and individualists. MacIntyre disavows having any loyalty to “community” as a basic unit and insists that many “communitarian” thinkers avow “the values of liberalism” he openly rejects. As he puts it,

My own critique of liberalism derives from the judgment that the best type of human life, that in which the tradition of the virtues is most adequately embodied, is lived by those engaged in constructing and sustaining forms of community directed toward the shared achievement of those common goods without which the ultimate human good cannot be achieved. Liberal political societies are characteristically committed to denying any place for a determinate conception of the human good in their public discourse, let alone allowing that their common life should be grounded in such a conception.

He goes on to explain that “on the dominant liberal view, government is to be neutral as between rival conceptions of the good,” a neutral arbiter over a plurality of conceptions. However, “in fact what liberalism promotes is a kind of institutional order that is inimical to the construction and sustaining of the types of communal relationship required for the best kind of human life.” This critique of liberalism is thus thoroughgoing and all-encompassing, applying equally to the American right as it does to the American left. Those called “conservative,” MacIntyre says, are often wedded to things like free market economics that he takes to commit the characteristic errors of liberalism by undermining the conditions of those communal relationships.

It is tempting for MacIntyre's ostensible followers and critics to see in his virtue ethics a kind of nostalgia.

It would take more space than I have here to articulate a response to this critique of liberalism, and any I could articulate would surely fall short of defeating the arguments MacIntyre makes at length throughout his works. Many defenders have responded, and many critics of liberalism have shared and advanced his critiques, and I need not rehash the dialogue in full here.

It is crucial to note, however, that those who seek to defend liberalism at length are done great favors by MacIntyre in his work. These defenders of liberalism cannot cleanly embrace MacIntyre’s thought wholesale, else they would no longer be defenders of liberalism. Despite this inherent tension, they would do well to acknowledge that MacIntyre has, through his decades of scholarship, presented perhaps the key argument that must be addressed when defending liberalism, particularly by those with philosophical or religious commitments MacIntyre takes to be contrary to liberalism.

Those Christians, for example, who believe in a “determinate conception of the human good” and yet still defend liberal institutions, markets, and the rest must do so, if they hope to be most effective defenders of liberalism, in the terms that MacIntyre set. They must, in other words, find something within liberalism that does not undermine those features essential to the “best kind of human life.” A committed liberal, faced with MacIntyre’s work, then can become a self-improving advocate of liberalism, seeking within the tradition the practices that can sustain this kind of life.

This is no easy task. The stage for the argument, however, was set at least as far back as MacIntyre’s “Notes from the Moral Wilderness”: A compelling moral critique of communism must come from a system that can demonstrate it has not been arbitrarily chosen, but one whose good for human beings as human beings is demonstrable. In this task at least, MacIntyre believes liberalism has failed. Its proponents must rise to its defense on these terms, perhaps by articulating how a definite conception of human good can be articulated within the liberal tradition and how the communal relationships that foster that good can be protected and preserved, rather than undermined, by liberalism.

One such attempt at advancing this project came famously from the work done by Rod Dreher in The Benedict Option.For many outside academia, Dreher’s writing was a kind of introduction to MacIntyre through the famous conclusion to the latter’s After Virtue, where he says that the modern world awaits “another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.” Interpreting this passage himself in the prologue to After Virtue’s third edition, MacIntyre wrote:

Benedict’s greatness lay in making possible a quite new kind of institution, that of the monastery of prayer, learning, and labor, in which and around which communities could not only survive, but flourish in a period of social and cultural darkness. … It was my intention to suggest, when I wrote that last sentence in 1980, that ours too is a time of resisting as prudently and courageously and justly and temperately as possible the dominant social, economic, and political order of advanced modernity. So it was twenty-six years ago, so it is still.

Taking these sections and his understanding of MacIntyre as a whole, Dreher set out in his Benedict Option to cast a vision for Christian communities that would fulfill this role. His work has often been criticized for advocating kinds of Christian enclaves, whereas MacIntyre’s praise of St. Benedict was for the monk’s creation of monastic communities that integrated into their surrounding secular communities to the benefit of each in this “period of social and cultural darkness.” Modern versions would do this not by rejecting or undermining the surrounding liberal order but rather by taking advantage of the resources offered by liberal freedoms to establish parallel communities pursuing Christian goods, preserving habits and practices against the surrounding culture that so often undermined them.

MacIntyre disavows any loyalty to 'community' as a basic unit and insists that many 'communitarian' thinkers avow 'the values of liberalism' he openly rejects.

When publicly questioned about Dreher’s book and his influence on it, MacIntyre disavowed it, much as he had previously disavowed his conservative and communitarian admirers. His accusation was that the sentence was read in isolation and was being used, ironically, to advocate for “a withdrawal from society into isolation,” a form of conservatism that was just a “mirror image” of liberalism.

Dreher, for his part, also disavowed that his advocacy was for “withdrawal” into “isolation,” but was instead supporting what he calls a “strategic withdrawal” for the sake of creating new practices and institutions that can foster the kind of life in the pursuit of virtue that MacIntyre praises. This rebuttal is, charitable readers of the book might find, a fair one. A more interesting criticism might be that advanced by Scott P. Richert in his 2017 review of The Benedict Option for Crisis Magazine, namely that the Benedict Option as a project “reads back on Benedict’s establishment of monasticism in the West an intent that is both far grander in scope yet far more mundane in purpose than what Benedict had in mind. What Benedict had in mind was to serve God, and through him his fellow man.” Insofar as a Benedict Option is pursued as an intentional project of Christian preservation against a hostile culture, a set of guidelines for a “movement” rather than a pursuit of practical wisdom, it is likely still to fall to MacIntyre’s rebuttal.

MacIntyre’s body of work includes several instances of philosophical biographies, treatments of major figures or thinkers whose lives and thought cannot be meaningfully separated. Long-time readers of MacIntyre were somewhat surprised, for example, to find a large portion of his final completed book, Ethics in the Conflict of Modernity, devoted to descriptions of the lives of four figures ranging from a Soviet writer to an American Supreme Court justice. Thus far in the book, he writes, he has laid out the following conclusion: “It is that agents do well only if and when they act to satisfy only those desires whose objects they have good reason to desire, that only agents who are sound and effective practical reasoners so act, that such agents must be disposed to act as the virtues require, and that such agents will be directed in their actions toward the achievement of their final end.”

If I may be so bold as to summarize, MacIntyre’s point seems to be that, as Aristotle says, virtuous people, prudent people, will desire and feel what they ought, will act on the basis of these desires in their practical lives, and in so doing will be pursuing their “final end.” MacIntyre further says that such a philosophical conclusion “can be understood adequately only by attention to the detail of particular cases that in significant ways exemplify it, not imaginary examples, but real examples.” In other words, we must see philosophy practiced by practical reasoners making choices on good bases. We learn much about philosophy, then, from the lives of those exercising practical reasoning, not just from the reading of texts or the contemplation of concepts.

Readers approaching MacIntyre will find, I argue, a life that models those about which MacIntyre himself wrote. His intellectual trajectory showed a willingness to enter into conversations with rival traditions, to take their insights into account, and to, most importantly, change his mind. As the figures MacIntyre writes on in Ethics in the Conflict of Modernity and elsewhere can serve as models for readers, so too can MacIntyre’s own philosophical biography. This need not be the equivalent of hagiography; MacIntyre says that those he studies in his book “are agents who are, like the rest of us, not yet fully rational, who are still learning how to act rightly and well.” They serve ultimately as models or guides, moral exemplars as virtue ethicists often describe them.

I once had the opportunity to meet writer and director Martin McDonagh. At the time, McDonagh was filming Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri outside Asheville, North Carolina, and he made an appearance there at a local indie bookstore for a Q&A time and a meet-and-greet. When given the chance to ask him a question, I seemed to stump him a bit. I attend a small, conservative, Christian liberal arts college, I explained, and your movie In Bruges is a campus favorite. The mostly conservative Christian college students simply love your work. Why is that, do you think? He laughed and said he couldn’t possibly make sense of the appeal.

In a similar, though more serious way, MacIntyre remains an influence on those far outside his own discipline, even those with whom he shared significant disagreement. MacIntyre’s responses during his life to those who saw him as an ally might suggest that those who associate with the American conservative movement and its offshoots are reading him poorly, co-opting him badly, and so on. But to the extent that we agree with MacIntyre about the necessity of ethical enquiry, to the extent that the practice of philosophy is meaningfully a practice and not simply a collection of abstract principles, it seems to be a thoroughly MacIntyrean approach to place his philosophy in conversation with one’s own, to extend his insights into contemporary moral and political debates, to take on the intellectual virtues he modeled of entering into the traditions of others, assessing them internally, interrogating our own traditions with similar rigor, and above all to be willing to change our minds when this enquiry leads us to new conclusions. MacIntyre modeled this in his work and life, and those who want truly to adopt his method, rather than take his developing thought as dogma, should go and do likewise.