“So are you with that conference upstairs? Is it political? We’re both kind of into politics.”

I had finally made my escape after my first full, long day at the National Conservatism Conference and was sitting just outside the Orlando Hilton beside an open fire pit with a drink, trying to wrap my mind around just what “National Conservatism” meant.

In November of 2021, scores of speakers, activists, politicians, and just plain fans descended on the Orlando Hilton to attain a vision of what the future of American conservatism was going to look like post-Trump and post-establishment conservatives. Did I mention there were totes?

My questioner was a slender young man in his early 20s who was accompanied by a woman of the same age holding a generously filled glass of wine. They had just come from the hotel bar above and I would later learn that the couple were from St. Louis; he had a job interview in the area tomorrow; and that, should he get an offer, they were exploring the possibility of moving to Orlando.

“Yes,” I said, “I’m attending the conference for work, and it is political.” More political than I anticipated, I thought to myself.

“Republicans or Democrats?” he asked.

A trap! Or perhaps an opportunity … an opportunity to begin putting into words what National Conservatism might mean to those curious.

“Mostly Republicans, but Republicans who are concerned about the Republican Party and want to take it in a different direction.” My articulation was undoubtedly shaggier and baggier than this at the time.

“Huh,” said the young man.

His companion now spoke: “We actually kind of liked Trump. He kind of told it like it is.”

I had clearly given them the wrong impression.

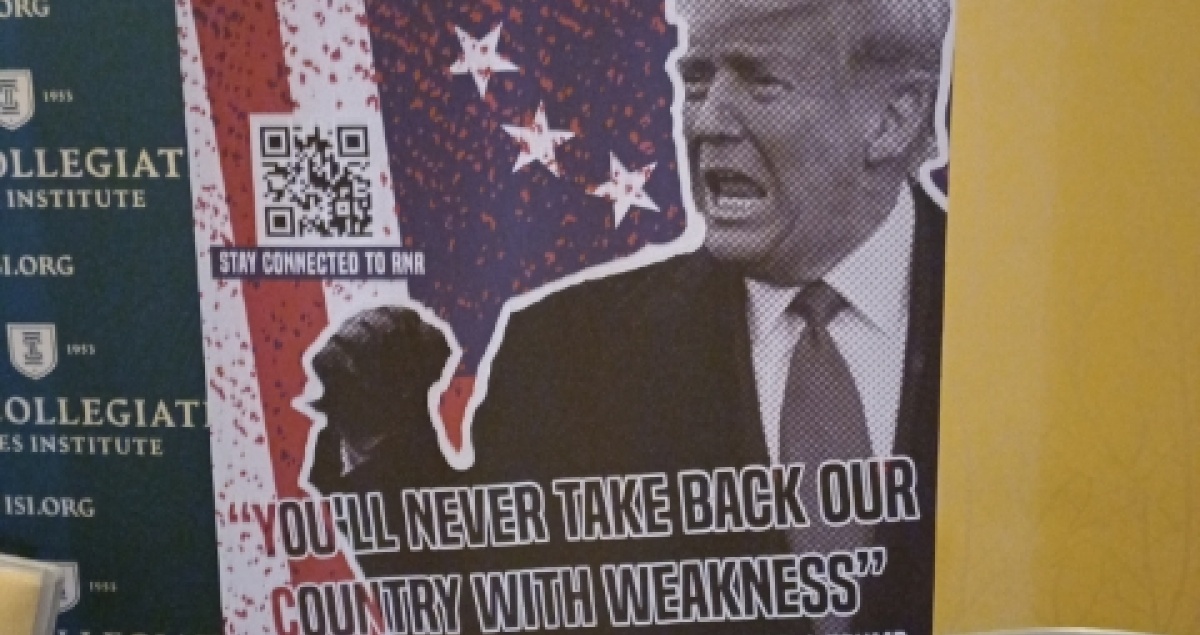

Prior to the opening conference session, I noticed a vendor table flanked by two 6-foot-tall banners. One featured Florida’s governor, Ron DeSantis, and the other former president Donald Trump. At the base of the former president’s banner was a quote—“You’ll never take back our country with weakness.” Always visit the vendor tables.

In a previous life, I worked as an audiovisual technician setting up rooms and running video and sound for conferences of all kinds. You can learn a lot about conferences from their vendor tables, schedule, audience, physical footprint, and even swag!

The aforementioned table was for an organization dedicated to political advocacy, but there were several right-wing media organizations that also had booths. Conservative magazines were well represented, and there was a children’s book publisher focusing on biographies of figures both political and cultural that could be broadly considered conservative, or at least marketed as such. And there were, of course, think tanks, of both American and Hungarian origin. These organizations were all more or less explicitly of the right, interested in disseminating ideas, and secular.

The schedule for the National Conservatism Conference was the most packed I’ve ever experienced. There were 24 plenary speakers, panels, and keynotes over three days, as well as 15 breakout sessions featuring 52 panelists. This represents a tremendous commitment by the Edmund Burke Foundation, the sponsor of the conference, of both time and resources. If anyone were to walk away from this conference unconvinced of the NatCon vision, it would not be because of a lack of talking and talking and talking.

Outside smaller-scale academic conferences, I had never seen a conference with a smaller speaker-to-participant ratio. There was also a generous amount of space in the main conference room dedicated to the press, as well as for the team of audiovisual technicians recording the conference’s plenary sessions. Seating on the main floor for attendees was ample, too ample. Often, perhaps due to the rigorous schedule or flight issues, which were plentiful, the main conference room appeared half empty. Most of the fellow attendees I met were either students or involved in conservative movement groups or think tanks like myself. Who exactly was this conference for?

How does one make sense of the unique structural realities of the conference itself? Is there a political economy of conferences? A critical conference theory?

Just as the proof of the pudding is in the eating, the proof of the conference is in the swag. Upon registration, I received a National Conservatism tote bag filled with NatCon goodies. There was, of course, a pen, but also a magnet clip, coffee mug, and journal, all in variations of the conference color scheme of orange, blue, and white. When Chuck D of Public Enemy remarks: “Red, black, and green, you know what I mean?” we know him to mean Black Nationalism. In the distant future, when some National Conservative rapper similarly intones, “Orange, blue, and white, you know it’s tight right?”—will we understand?

This would be a mark of success in National Conservatism brand identity. National Conservatism is by no means merely a brand, but from many of the speakers at the conference I listened to, it seemed primarily to function that way. In this sense National Conservatism is, at least in part, something like the NatCon coffee mug I received: an empty vessel labeling everything it contains as “National Conservatism.”

National Conservatism has often billed itself as “against the dead consensus,” rejecting the midcentury configuration of American conservatism arising from various conservative thinkers such as Frank Meyer and William F. Buckley Jr., both at the center of the early National Review. This “dead consensus” is typically referred to as fusionism, a synthesis of traditionalist and social conservatism and what is often called right-liberalism or right-libertarianism. The historical impetus for this fusionism was the threat of international communism.

It was surprising to see, then, just how many of those speaking at the conference seemed to be, if not in name, then in substance, fusionists. Marcell Felipe, Cuban American attorney and activist, gave an impassioned address the opening night of the conference titled, “Why Cuban Americans Get the Marxist Threat.” The fiery address was not only ferociously anticommunist but extoled the virtues of former president Ronald Reagan. Such principled anticommunism coupled with praise of perhaps America’s most fusionist president from the main stage of National Conservatism indicates that the consensus’s demise has been greatly exaggerated.

Glenn Loury, professor of economics at Brown University, gave a moving address on “The Case for Black Patriotism.” In it he argued for a transracial humanism grounded in the dignity of the human person and a shared commitment to and solidarity with fellow citizens of all races. While Loury rightfully called attention to how the pathologies of identity politics on the left often undermine such a vision, he also warns that the new nationalism on the right can “sometimes be insufficiently attentive to … an unhealthy version of patriotism, chauvinism, and jingoism,” which is particularly dangerous, “especially if tainted by racial identity mongering.” Loury’s speech, while well received, seemed more a sympathetic address to National Conservatives than a speech from a National Conservative.

No such surface-level ambiguities existed in the chairman of the National Conservatism Conference Chris DeMuth’s speech, “Why I Am a National Conservative.” It was however curious that a former Reagan administration official and longtime president of the American Enterprise Institute would now style himself a National Conservative committed to replacing the “dead consensus” of fusionism.

In his address, DeMuth offered an explanation for this shift, alluding to the ideological realignment of Irving Kristol and his fellow neoconservatives, who moved from left to right throughout the 1960s and ’70s, arguing, in Kristol’s words, that they were liberals who had been mugged by reality. So it was somewhat ironic to hear DeMuth play off this trope: “NatCons are conservatives who have been mugged by reality,” he declared. The reality that mugged both the neocons of the past and the DeMuths of today is the radicalism of the American left—then and now.

But does the National Conservative experience of the radicalism on the left today work analogously to what provoked neocons in the 1960s and ’70s, causing the NatCons to move from the right to the far right? For DeMuth the answer is complicated: “There are a variety of views among intellectuals, among national conservatives, about our predecessors in 20th-century conservatism.”

DeMuth feels that the most vocal critics of the so-called dead consensus go too far in attributing the social crises of our time to the failures of conservatisms past: “This exaggerates the potential of ideas to affect the course of society.” He pointed to the successes of fusionism, from the economic boom of the 1980s and revival of New York City in the 1990s to the salutary influence of originalism in judicial interpretation resulting in the restraint of government power.

DeMuth went on to describe himself as a “free market man” and even a “libertarian,” though one of an empirical rather than a doctrinaire bent. His model of political economy is Adam Smith, the champion of the system of natural liberty, and to young people interested in the relationship between freedom and virtue he commended the works of Catholic theologian Michael Novak. If this was National Conservatism, count me in! But if this was National Conservatism, what possible reason could there be to count fusionism out?

Is one a National Conservative by simple declaration? And is the substance of that declaration simply: “I’m not a regular conservative; I’m a cool conservative”?

At this point I was seized by a truly dizzying possibility—is it fusionism all the way down? Yoram Hazony, chairman of the Edmund Burke Foundation and president of the Herzl Institute in Jerusalem, in the most revealing lecture of the conference, “De-Fusionism,” provided an answer. He began with an examination of the conference vibe: “I think it’s going well. You know how I know it’s going well? I know it’s going well because I can feel—this is corny, all right, brace yourselves—I can feel the love in the room. I can. That feeling that you feel is the people making new friends, coming together, and building an alliance that can win.”

For Hazony, National Conservatism is not merely a personal brand. National Conservatives are not some undefined liquid poured into National Conservatism mugs. National Conservatism is more like the National Conservatism tote containing multitudes of branded National Conservatives and, as we shall see, even some anti-Marxist liberals (terms and conditions may apply). National Conservatives are friends united to win. To win what? Elections.

Hazony sees the social crisis of our time as a “neo-Marxist cultural revolution” that is corrupting liberal institutions worldwide. In a sense this threat is familiar, resembling the struggle against international communism throughout the years of the Cold War. This threat was, according to Hazony, met ably by fusionism, which he defined as a “public liberalism” joined to a “private conservatism.” This synthesis advanced economic, social, and individual freedom in political institutions while promoting reverence for God, family, and country in the private lives of individuals.

Fusionism, while having successfully resisted international communism, is nevertheless ill-suited to combat today’s “neo-Marxist cultural revolution,” Hazony insisted. The reason? Since the 1960s, “private conservatism” had been eroded by “public liberalism.” Hazony did not get into meddlesome details about exactly how that happened, but he assured the audience that this erosion was responsible for everything from corporate decisions to offshore its manufacturing to China, the depopulation of the American heartland, censorship on social media platforms, pornography, and mass immigration.

This account of the role and function of liberty in public life is starkly different from Lord Acton’s, which views “public liberalism” as enabling, not eroding, “private conservatism”:

Now liberty and good government do not exclude each other; and there are excellent reasons why they should go together. Liberty is not a means to a higher political end. It is itself the highest political end. It is not for the sake of a good public administration that it is required, but for security in the pursuit of the highest objects of civil society, and of private life.

Here liberty (public liberalism) is the necessary but not sufficient condition that enables the pursuit of public and private virtue (private conservatism). This insight, that the good must be freely chosen, underlies the old fusionism that Hazony wishes to discard in the belief that liberty has, since America’s triumph in the Cold War, poisoned and hollowed out “private conservatism,” causing the social order to become septic.

Hazony made clear he is not wholly critical of liberalism: “I’m not here to knock individual liberty. Individual liberty is fantastic, [and I] wouldn’t want to live in any other place than a country that cherishes individual liberty.”

It is perhaps for this reason, although he never explicitly stated this, that he commended a new fusionism between conservatives and anti-Marxist liberals but with significantly different terms and conditions.

The new fusionism must explicitly reject all forms of egalitarianism except in the face of grave injustice. Hazony gave the example of the struggle against Jim Crow; he sees racial egalitarianism as a fundamental part of America’s vocation as a nation since the end of the Second World War. Equality between the sexes, between citizens and foreigners, married and unmarried, homosexual and heterosexual, however, should be rejected.

A rejection of egalitarianism for minorities is grounded in what Hazony sees as an imperative to have a strong public culture shaped by the majorities in any nation.

Hazony is not entirely insensitive to the needs of minorities in society. As a Jew he believes that, in this country, American Jews need “a carve-out to be able to pursue their traditions, to send children to their schools, to not be persecuted …, abused, or killed.” He employed this language of “carve-out” again when discussing homosexuals, saying, “Give them their privacy. Nobody wants to be arresting people in their bedrooms.”

This language is very different from the way Americans have historically talked about individual rights, and is in some ways more similar to the way modern progressives talk about the rights of groups or communities. Unlike modern progressive understandings of the rights of communities, however, these carve-outs would be essentially private to the communities themselves and have no standing in the public square. This is an inversion of Hazony’s understanding of the old fusionism. His new fusionism would be one of “public conservatism” joined to a “private liberalism.”

Hazony believes such a new fusionism would result, in countries with a large Christian majority such as the United States, in a great Christian nation with a Christian public life.

The wide range of doctrinal, moral, and political convictions among American Christians was not addressed by Hazony. Nor were the possible motivations for anti-Marxist liberals to embrace these new terms and conditions. Neither was the electoral viability of such a new fusionism. It was more of a just-so story wrapped up with a “wouldn’t it be nice” riding on a wave of good National Conservative vibes.

To paraphrase Emerson: Vibes, though a bad regulator, are a powerful spring. There was a palpable, if sometimes manic, energy at the National Conservatism Conference. While National Conservatism is a brand aspiring to be a political coalition, it is also clearly an attitude. While the metaphor of National Conservatism as a tote bag obscures powerful personalities, perhaps another piece of conference swag—the journal—can serve as a metaphor to shed light on the NatCon temperament.

The journal is an essentially private form of writing. It is the place where we write out the desires and dreams we’re reluctant to share with others. It’s the abode of the purpliest prose and our most outlandish ideas. Its very form gives us license and permission to express ourselves as we wouldn’t elsewhere. The late, famously unconstrained vampire novelist Anne Rice attributed to Kafka her essential writing philosophy: “Don’t bend. Don’t water it down. Don’t try to make it logical. Don’t edit your own soul according to fashion. Rather, follow your most intense obsessions mercilessly.” What happens when you wrap an id, that unconscious part of the human psyche of desires and dreams, in the cover of an orange, blue, and white journal titled “National Conservatism”? What happens when the rigid, undiluted, nonsensical, unfashionable, and obsessive parts of ourselves drive our political rhetoric and practical politics like Mr. Toad on a wild ride through our obsessions?

Perhaps the most intense obsession of the conference, from speakers, on panels, and among the participants, was critical race theory (CRT). Christopher Rufo, senior fellow and director of the Initiative on Critical Race Theory at the Manhattan Institute, is both its greatest popularizer and critic. He was also the most well-received speaker at the National Conservatism Conference. He began by introducing himself as a writer and documentary filmmaker but told the crowd that he is best known to the audiences of MSNBC and The New York Times as “a liar, a racist, and a propagandist.” The crowd loved it. He views his own work as a sort of counterrevolutionary activism against an ongoing neo-Marxist revolt that has captured our institutions.

For Rufo, the nature of this conflict is fundamentally cultural: “The fight today is no longer along the axis of economics but primarily along the multiple axes of culture, race, gender identity, etc.” He sees his role as primarily making this fight public through reporting on and releasing documents from corporations, government, and schools that demonstrate how deeply immersed in identity politics they are. This information-gathering and dissemination has led, according to Rufo, at least in part to an “unexpected and totally organic grassroots uprising of parents at local school districts saying, ‘Enough is enough.’”

He thinks this sort of activism should not be channeled toward reforming and reclaiming institutions but rather in “laying siege to the institutions, exposing them for their corruption, exposing them for their waste, exposing them for their hostility to the values of the vast majority of the American people.” And this because “politics is downstream from state institutions. … It’s the dominant ideology in the federal agencies, it’s the dominant ideology in the public universities, it’s the dominant ideology in public K–12 education.”

As Rufo outlined a strategy to mobilize and utilize populist outrage against American institutions, the crowd was enraptured. This was not a simple call to reform but one to something far more radical. It was not an acknowledgement of deep-seated problems within institutions but a charge that those institutions are fundamentally enemies of the people. He suggested to the crowd that by harassing, frustrating, and finally dismantling those institutions, they have nothing to lose but their chains.

These are things that conservatives simply don’t say! Respect for the nation, its institutions, and fellow citizens was simply not in evidence. Disdain from political opponents was both welcomed and flung back at them with abandon. Lord Acton’s belief that “liberty is the delicate fruit of a mature civilization” and Buke’s admonition that “our patience will achieve more than our force” were simply ignored.

Rufo’s unconstrained and confrontational rhetoric was at least presented within a theory of institutions and politics. Josh Hammer, opinion editor of Newsweek and research fellow with the Edmund Burke Foundation, on the other hand, gave an address that was simply untethered and unhinged.

If there were a game whose object was simply to be as right wing as possible, Josh Hammer would be undisputed champion. Hammer’s speech, “National Conservatism: The Only Path,” contrasted the promise of a “muscular National Conservatism” with the failures of what he called “Conservatism, Inc.”—fusionists and libertarians. Where they have failed, National Conservatives will (1) triumph through force of will, (2) wield power, and (3) “affirmatively reward our friends and punish our enemies within the confines of the rule of law.” The “rule of law” caveat is important, as it places the National Conservatives firmly on the opposite side of the Conan the Cimmerian barbarism line.

The notion that “the specific political distinction to which political actions and motives can be reduced is that between friend and enemy” comes from the German jurist, political theorist, and National Socialist Carl Schmitt. Schmitt also wrote the article “Der Führer schützt das Recht,” which argued that the murders ordered by Adolf Hitler on the Night of the Long Knives were the highest form of administrative justice. I sat in my chair dumbfounded at the conclusion of Hammer’s speech. I was still dazed when the stately and dignified Mary Eberstadt took the stage remarking that the energy in the room reminded her of the early days of the Reagan revolution.

My brain was officially broken.

It is impossible to give a comprehensive account of the entire National Conservatism Conference in a magazine feature. It was large and contained multitudes. Some identify with National Conservatism on a purely superficial level, as a brand. Others see it as a political movement, a nascent coalition, and the wave of the future. Others take it as a sort of license to shed constraints and “tell it like it is,” whether it is or not.

The couple whom I first tried to explain National Conservatism to that night by the fire outside the Orlando Hilton took my description of the National Conservatives as “Republicans who are concerned about the Republican Party and want to take it in a different direction” to mean that those Republicans were hostile to Donald Trump. The curious absence of Trump in this discussion of National Conservatism is no accident. He was rarely mentioned. Ted Cruz did mention the former president in his address to the conference, saying, “Look, Donald Trump is a unique individual …”—a knowing pause—“so many Americans love this man … because after all the weakness and surrender and imbecility, thank God the man stands up and fights.”

This was very similar to the language of the former president that was quoted on the banner outside the hall: “You’ll never take back our country with weakness.” I took a picture of the banner on the last day of the conference; it seemed like a real point of resonance between the former president and the National Conservatives. It was only later that I realized the quote in question was from his address on January 6, 2021, the day of the riot at the United States Capitol.

In considering National Conservatism as brand, coalition, or invitation to stop being polite and start being real, my judgments are varied. National Conservatism as a sort of empty vessel is largely harmless if uninteresting. National Conservatism as a political coalition, a tote containing the old fusionist coalition under new terms, seemed both under-theorized and untested. National Conservatism as a blanket permission to indulge our desires, to reward friends and punish enemies through rhetorical as well as practical politics, was positively immoral. It is plainly contrary to Christ’s admonition to “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you” (Matt. 5:44).

For our politics to change for the better, we don’t need a new brand, a new coalition, or a new license to dispense with our obligations to each other. We need a new heart: “That ye may be the children of your Father which is in heaven: for he maketh his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sendeth rain on the just and on the unjust” (Matt. 5:45).

OK, hold the eye rolling, please. Like Yoram Hazony, I too want to see America as a great Christian nation with a Christian public life. This is the most surprising and startling common ground I share with my National Conservative hosts. How it can be accomplished by branding, political coalitions, and unleashing our ids is something I do not understand, for the kingdom of God does not come with signs to be observed: “Neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there! for, behold, the kingdom of God is within you” (Luke 17:21). Lord Acton warned us long ago of the dangerous temptation to view the nation as coextensive with the state—of equating the national interest with the common good. A Christian nation and public life is already in our midst, but only accessible through the service we render in all our vocations to God and neighbor.