Long before American higher education became almost a wholly owned subsidiary of progressive thought control, literature departments fell much earlier to many of these same forces, with the deconstruction of classic texts by “new historicism,” “cultural materialism,” or “post-colonialism.” One of the biggest targets of these postmodernist efforts was and remains the grand work of William Shakespeare. Understanding this ongoing phenomenon and what it all means is the subject of R.V. Young’s Shakespeare and the Idea of Western Civilization.

The deconstruction of classical texts seeks also to rip up the foundations of Western civilization. Can we find in the works of the immortal Bard the key to defending the West, a certain call to “readiness”?

By R.V. Young

(Catholic University Press, 2022)

The sustained attack on Shakespeare should not be surprising. He is, Young observes, “the consummate expression of the Western literary and cultural tradition.” Young arrives at this judgment by a distillation of the essence of Western civilization: “its solid adherence to profound and substantial tradition blended with the leaven of an inquiring, critical spirit.” Shakespeare “embodies” Western culture with his plays, which demonstrate the West’s “deepest commitments of its moral and spiritual vision” while also “continually subjecting them to scrutiny.” Scrutiny, that is, not denial, evasion, or the outright refusal to acknowledge the West’s grand tradition.

This witch’s brew of literary study is, Young argues, nearly incomprehensible. Its insanity only deepens because of the status that Shakespeare has obtained not only as “the principal poet of Western civilization” but also because he has “transcended his origins in the West” with study and performance of his work occurring in China, India, Japan, and many other non-Western countries. Shakespeare’s work is lauded by artists in other civilizations as a tremendous achievement, speaking to them directly and poignantly. This means that Shakespeare contradicts one of the theories of postmodernism: that literary work is a direct product of social ideology. Could a work limited by ideology and confined by its cultural conditions be met with such a cross-civilizational reception?

One measure of an enduring work is that we keep going back to it to learn more from it and about ourselves.

The forces of ideological avarice that have preyed on Shakespeare’s body of work are engaged in another project altogether. There are profound “moral and political consequences” stemming from it, as these ideologies reduce ideas to “physical processes,” meaning that the “material conditions” and “power relations” of a society that a writer inhabits are the determinative factors of the writer’s work and “displace inspiration and vision as factors in the evaluation of literature.” These ideologies basically reduce to the point that the only thing of value in literature

is a varying discursive formation constructed by the ideological energies and constraints of successive phases of social history, and any individual title, say, The Tempest, is likewise merely an empty signifier, the locus of diverse ideological constructs associated with an indeterminate number of ink and paper exemplars and the utterances and gestures of staged performances.

We deal here with a form of insanity, Young notes.

The author reminds us that literature comes from imagination and intellect. Great artists transcend their circumstances and their culture even as they work from within it. One measure of an enduring work is that we keep going back to it to learn more from it and about ourselves. The separation of time, culture, language, and politics are not barriers to such learning, but an invitation to go even deeper in our study. And such a process is also inherently joyful. The Marxist, feminist, gender literary scholars can see only themselves in the text, a text they manipulate for their own ends. As Young notes at one point, with these scholars you must doublecheck everything they say about a work, knowing in advance that other ideological forces are lurking.

Young does not analyze the entire Shakespeare corpus but evaluates the Bard’s work as it presents love and marriage, philosophical realism, race, freedom and tyranny, and the Gospel and natural law. In each chapter, the author sets forth that Shakespeare is at pains to present the truth of the human condition in these contexts and how error, pride, and sin mar man’s efforts to live well and flourish. Shakespeare is nothing if not exacting in how Western civilization has combined reason, revelation, and the questing spirit to illuminate the truth of the human condition. And this is his singular excellence whose truth unfolds as we read, discuss, and perform his plays.

Shakespeare’s most moving presentations of love and marriage are found in the comedies, Young insists. We repeatedly turn to Romeo and Juliet and Othello, but in The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado About Nothing, Twelfth Night, and As You Like It, Young argues, we see the emergence of attraction, romance, balanced by the good of companionate marriage as its outcome. Love between couples is not private but inherently social and institutional. What begins as desire must be elevated and “also seen as a grave responsibility.” Young further observes that “nowhere is the alienation of contemporary men and women from the Christian traditions of the past—and hence from the moral vision embodied in Shakespeare’s plays—more manifest than in the realm of sexual morality.”

The Marxist, feminist, gender literary scholar can see only themselves in the text.

We are also doubly separated from the classical world’s understanding of marriage, which, Young writes, could not even place married love on the same plane with male friendship. Marriage was not regarded by Aristotle as a friendship of equals, even though it was a special friendship. Similarly, Catullus compares his devotion to a woman as a father loves his sons. That, however, has changed. Marriage becomes something between equal partners, however, at least in moral stature, in Much Ado About Nothing. Young observes that Shakespeare doesn’t exactly say this in his plays. For example, the meaning of love and marriage is “generated by the plot” in Much Ado About Nothing, revealing “contrasts between two approaches to marriage and between the love of a man and a woman and nonsexual love between friends.”

Two of the characters in the comedy, Beatrice and Benedick, maintain a witty, sardonic banter between them, one that is led by desire but could only be sustained because each regards the other as a worthy partner. They “woo peacefully” but gain a thoroughgoing knowledge of one another. The contrast is with Claudio and Hero who casually and passively walk into the betrothed state, until Hero falls victim to a wicked accusation of cheating by the unsavory character of Don John. Claudio accepts the accusation’s veracity, while those who truly know Hero’s character, particularly Beatrice, cannot accept it. Hero falls ill and unconscious because of the slander. The difference with Beatrice and Benedick could not be more obvious as they have slowly realized their love for one another. But that realization of mutual love and desire isn’t enough, Young adds.

Benedick must place Beatrice higher than his love for male friends. She tells Benedick to kill Claudio owing to her rage at his acceptance of the accusation against Hero. Benedick doesn’t actually kill Claudio, but he also rejects the charge against Hero, and implicitly Claudio’s judgment in believing it, choosing to believe in Beatrice and Hero’s innocence against the word of male companions. As Young says, Benedick must “be a man instead of merely one of the boys.” Beatrice’s wit, graciousness, and strength have made her what her name suggests, blessed and beatified. Benedick suggests benediction. They are a worthy match. All that being said, what is affirmed in the play is chastity, duty, sacrifice, and love, the sublimation and then integration of human desire into an act of gift and promise in marriage. Is this not what the play’s postmodern critics simply cannot abide?

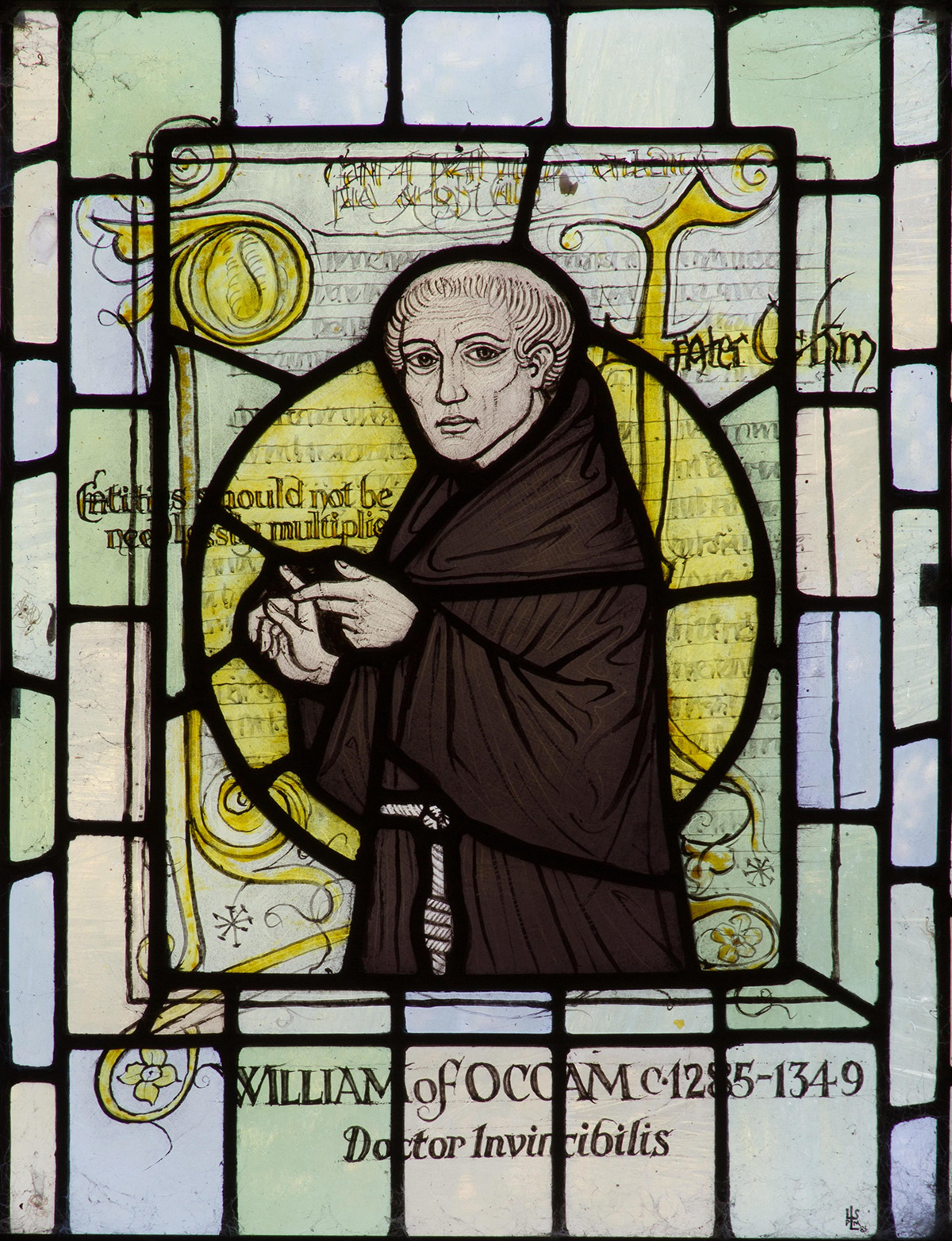

Turning to the tragedy plays, Young argues that Shakespeare clearly makes the decision to reject nominalism, the philosophical notion that there are no universals, just the mental groupings that we arbitrarily give to objects that appear to be in the same class with one another. Young traces the advent of nominalism to the 14th century theologian William of Occam, its influence working its way through Western philosophy and making its appearance in parts of the Reformation. In short, Shakespeare was confronted with choosing either the philosophic universalism of Aristotle and Aquinas or the absence of universal truth in Occam. Nominalism inherently cashes out, Young thinks, in an increasingly subjectivist individualism where will displaces reason and reflection on nature itself. Tragedy, Young observes, is built on moral realism, on the notion that we can’t just make up our own reality. Truth exists, difficult trials fall on men and women who are uncommonly good, who falter in Shakespearean tragedy. To embrace nominalism is to refuse the drama of life, which Shakespeare is demonstrating in his tragedies.

Perhaps no better example exists, Young cites, than Juliet’s famous soliloquy: “Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo? Deny thy father and refuse thy name…” She concludes, “Romeo, doff thy name, And for thy name, which is no part of thee, Take all myself.” Romeo should shed his name, family, and personal history for romantic desire. This is indeed a certain individualism, perhaps paralleling the rising individualism in the Protestant Reformation, creeping into Shakespeare’s world. But the explosion and crashing of Romeo and Juliet’s personal, hidden love with the concrete facts of their families, institutions, and society cannot be so easily wished away. We side with their love, finding Romeo and Juliet noble in their actions. Our society has been so firmly baked and defined by individualistic expectations, Young concludes, that we lose the overall substance of Romeo and Juliet and the overheated faults in the characters. Romeo refuses prudence, limits, and caution after he is banished, rushing headlong into disaster. He rejects the wise counsel of Friar Lawrence that he delay and be patient: “Thou canst not speak of what thou dost not feel.” A celibate priest cannot know the inner depths of eros, or, as Young notes, “Universal moral principles are of no force in the face of immediate, particular emotion.”

Of course, the other side of the drama is that their families and other institutions in society have become corrupt and unlovable. Nominalism’s quest to assert subjectivism as the substance of truth is never more powerful than in the breakdown of necessary institutions for social flourishing. What examples of love, patience, and decency have Romeo and Juliet’s families given them but a crabbed existence of hatred, jealousy, and violence? We find ourselves in many ways beset with the same general problem. Key institutions across American life are either dysfunctional or perceived as such, and often for good reason. The price paid is the loss of belief in moral principle, duty, and self-restraint, as many increasingly think that you get what you can for yourself because nothing else really matters or has weight and meaning.

How then to recover authentic freedom even amid tyranny? Shakespeare, Young thinks, does not give us an answer that most would be satisfied with. Julius Caesar, Hamlet, and Macbeth show us the diminished capacity for thought and integrity that marks any human path that commits itself to politics. There also may not be political solutions as such, just limitations, compromises, and reversals. In Julius Caesar and Hamlet, we see “tragic heroes” lose “their freedom of mind” by an encounter with tyranny. Shakespeare’s focus isn’t on political institutions as such, but “the spiritual destiny of individual human beings.” What makes tyranny tragic, Young states, is “less the use of force” and more “the spiritual deterioration, the diminished mental candor” affecting both tyrants and those who challenge their corruption.

Brutus is a tragic figure because he gives to politics a position of primacy that it cannot fulfill and one that will lead to the destruction of nonpolitical goods: friendship and marriage. Brutus plunges into the pursuit of a political abstraction that justifies killing Caesar, his friend. This path leads to civil war and chaos, and also leads to the name Caesar being applied to future leaders of Rome. Brutus descends into ideology and inherits the whirlwind, Young concludes. He remains, though, a noble character who permits politics to pull him into a situation that dissolves his life and those of others. To challenge a tyrant requires its own prudence, not merely aping the tactics of such a thug.

Hamlet, much like Brutus, faces the same predicament: How do I oppose a seemingly invincible tyranny? Hamlet learns from his father, the murdered former king of Denmark, that Hamlet’s uncle—now king of Denmark—was the slayer. What to do with this incredible turn of events? Hamlet evinces doubt but finds the means to act decisively, but he also kills indiscriminately to avenge his father. Tyranny has also reduced the candor of his free mind and made him less than he really is, which is a noble man. But Hamlet, perhaps under the Christian influence, grows and learns from the opposition he faces. Does Hamlet die a killer or with an enlarged soul? His death appears more hopeful than Brutus’—he acknowledges Providence and asks Horatio “to tell my story.” Hamlet’s death remains tragic, though, and its ending ambiguous. The bloodshed at the end of the play is caused by Hamlet, and he remarks at his death “—the rest is silence.” However, what he does learn, according to Young, is that to oppose a tyrant is “not to imitate the violence and deceit of the tyrant.” Rather, what he learns is what Hamlet calls “readiness.”

We might argue that Hamlet’s condition explains well the overall situation of Shakespeare’s work vis-à-vis the deconstructionist scholars. Hamlet overcomes his personal doubt to find the imagination and courage to oppose tyranny. We will have to do the same in many contexts to defend our civilization, exhibiting “readiness” as we confront those who in attacking the literature of the West are really launching “an attack upon the civilization itself.” Toward that end, R.V. Young’s book has opened Shakespeare to us in a compelling manner, outlining the case for why he sits in a high and exalted place in the Western imagination. Shakespeare’s stories have become part of us, guiding our souls and imaginations to a more capacious understanding of human excellence and tragedy. Young has liberated Shakespeare’s eternal gifts for a people made weary by the enfilading ideological fires of the academy. We owe him our gratitude.