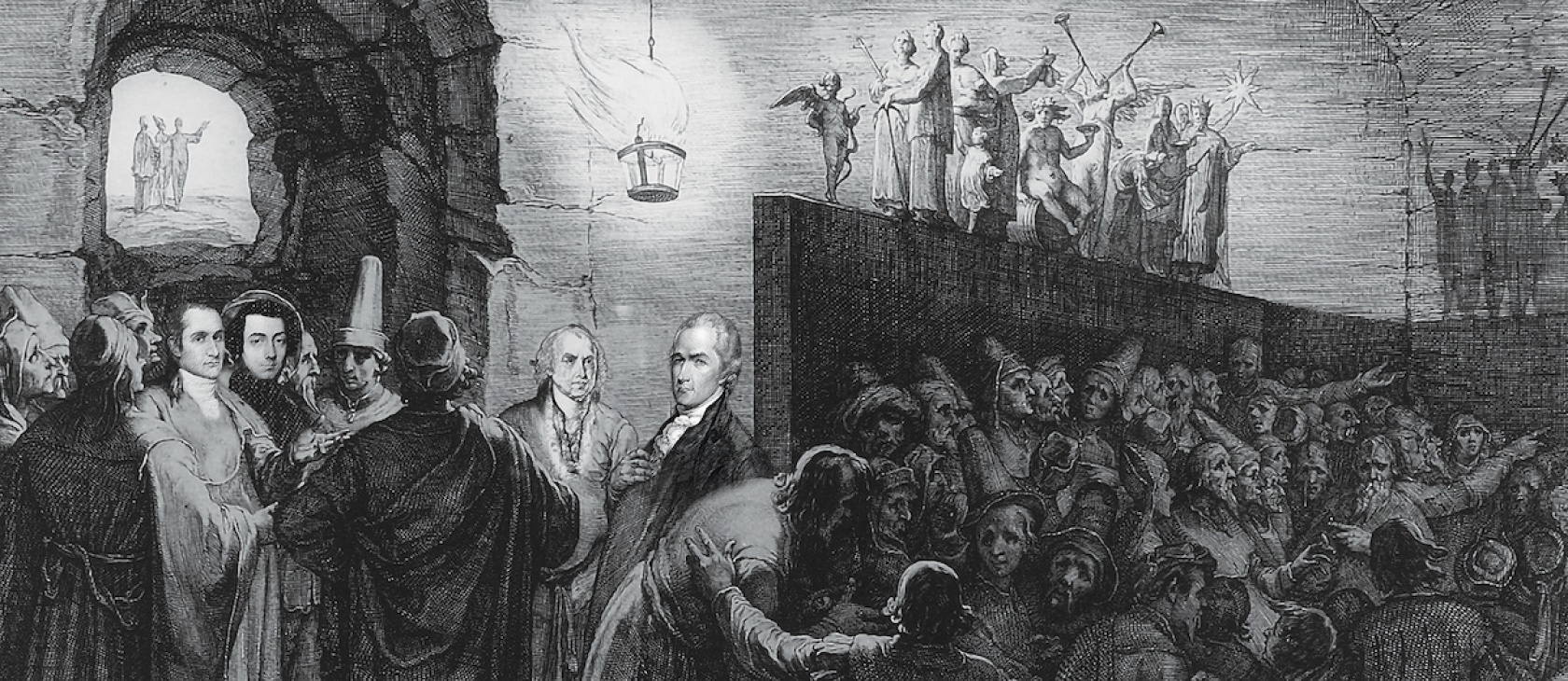

The expectations of justice reside deeply within us. Figures in both the Hebraic and Hellenic worlds placed the demand for a just society at the center of their work. Those demands have echoed through the ages and into our streets. At the earliest of ages we complain about things we deem unfair and dog our parents over broken promises. Of all the virtues, justice seems most ingrained. And yet it is the one most likely to create havoc and wreak confusion. We seem to have a clear understanding of what courage demands, and we rarely talk about prudence and temperance except elliptically, but our insistence on justice relates inversely to our understanding of it.

Justice is the watchword for today. We all seek it. But what is it? Would we recognize it if we saw it? And can the pursuit of justice pose a threat to the very freedoms it seeks to preserve?

Nowhere is this dynamic presented more compellingly than in the central text on the problem of justice: Plato’s Republic.On the one hand, Socrates is responding to the pleas of the youth of the city: What is this thing we call justice? How can we participate in the life of a city that has become so corrupt? Can one participate in politics without losing the integrity of one’s soul? What guidance can our elders give us? What prospects await us if justice cannot prevail?

These questions are perennial and point to the ongoing relevance of the dialogue, for nowhere are these questions more thoroughly explored nor the difficulty of providing answers more dramatically demonstrated. Indeed, like many of the dialogues, the Republic displays the drama of social life, the struggle and travails of the agon that rests at the center of our efforts to forge a mutually satisfying shared existence. This drama, we may observe, will always most keenly be felt by the youth of the city who, without the tempering influence of experience and its concomitant wisdom, turn their uncertainty and frustration into either collectivized radicalism or individualized hedonism.

The Republic is inexhaustible and thus resists summation, but I want to draw the reader’s attention to three main points, and then connect this to the problem of justice as conceived in our constitutional system.

Glaucon and Adeimantus, the brothers of Plato and students of Socrates, engage the latter in conversation in the home of Cephalus, one of the elder statesmen of democratic Athens. They are there at the invitation of Polemarchus, the son of Cephalus, who briefly attempts to defend the view that justice is doing good to one’s friends and harm to one’s enemies. Although Cephalus himself plays a minor role in the dialogue, his short-lived participation reflects the conventional wisdom of “those who have gone ahead of us … on a road which we too will probably have to travel.” Cephalus’ view of justice may be summed up as “being truthful, and giving back to others what you owe them,” a view that Socrates demonstrates might commit us to all kinds of wrongdoing. The details of the argument need not concern us as much as the fact that Cephalus has no capacity to defend the position.

The Republic displays the drama of social life, the struggle and travails of the agon that rests at the center of our efforts to forge a mutually satisfying shared existence.

This is the general problem with conventions, of course. Drawn from the Latin for “an agreement or a meeting,” conventions may be acceded to without being understood. Notice the root relationship to the word convenient and its meaning of “becoming suitable.” Conventions aren’t necessarily false or meaningless or unproductive of what is good, but neither are they necessarily true or meaningful or productive, and thus admit of critical investigation. In the hands of leaders such as Cephalus, no critical investigation has taken place, nor can it, in no small part because, as Socrates observes, Cephalus’ definition bears a relationship to both his wealth and his status. The effort to make of justice a universal value can’t be placed on so unsteady a foundation.

Descending and Ascending

The expectation that kings be philosophers or that philosophers be kings is an unrealistic one, but kings surely need philosophers as council. The good relates directly to the true, after all. At this point in the dialogue, the young people in the room cast a skeptical eye at Cephalus, for his “privilege” has insulated him from both the consequences of his definition and, more damningly, any existential need to question it. Cephalus no long shares in the same social and political world as the youth, except in the most rudimentary sense. Conventions are not fungible, but money is, and Cephalus notes that it is precisely his wealth that makes it possible for him to pay his debts, and thus “wealth is particularly useful in this context.”

A second feature of the dialogue involves its overall structure. The Republic both begins and ends with an act of descending, and throughout the dialogue we are treated to a series of contrasting ascents and descents. The famous allegory of the cave from book 7 is a microcosm of this overall structure. Having already descended into the cave, one of the prisoners breaks free from his chains and begins the process of ascent (beginning with the periagoge, or turning around—a conversion). The prisoner must then again descend into the cave, before ascending once again. The “city in speech” contrasts with the infirm polis; the paradeigma ek uranos (paradigm in heaven) contrasts with the earthly city of Athens.

This contrasting of opposites is central to Plato’s overall strategy of getting some traction on the truth by discovering what it’s not (or apophasis). Our understandings of justice are largely derived from experiences of injustice. Indeed, a central feature of the natural law is that it can receive very little, if any, positive explication. It acts largely as an injunction, such injunctions receiving their force from a deep moral sense. Antigone to Creon, Boethius to Lady Wisdom, Martin Luther King in the Birmingham jail, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn to his jailers, all attest to a higher order they discover as a result of experiencing breaches of justice (473d). C.S. Lewis states this well in Mere Christianity when he expresses the anger we experience when we briefly get up from a chair we are sitting in at a coffee shop and return to find someone has taken our place. “That’s my chair” has no legal claim, but it has a moral one. For Plato, as for the other youth of Athens, the determinative event of his life was that the city had put to death “the most just man I ever knew.” The condemnation at the trial of Socrates was, in fact, the condemnation of Athens.

Plato consistently draws on this moral sense that we have a longing for justice (443b). We might not have a clear idea of what is due another person, but we are familiar with the problem of pleonexia (getting more than one’s share) and how it both consumes and divides polity and soul. We might not have a clear idea of what a philosopher is, but we all have experiences with philodoxers, those lovers of opinion who never express an original or interesting thought. We may not be able to express the nature of beauty well, but the features of ugliness are readily apparent. We may struggle to find and tell stories that express the truth of who we are, but anyone with eyes to see and ears to hear can identify the proliferation of bad ones.

Tell Us a Story

The central point of the dialogue, that Plato is creating an educational polis, is often overlooked: The most powerful people in any society are neither statesmen nor plutocrats, but the storytellers (377b). Woe to us if our statesmen control the content of storytelling or the plutocrats have seized control of the instruments of storytelling. Socrates asserts that, virtue being the most important thing, stories that celebrate vice and undercut virtue must be prohibited (378b), for “a young person can’t tell when something is allegorical and when it isn’t, and any idea admitted by a person of that age tends to become almost ineradicable and permanent. All things considered, then, that is why a very great deal of importance should be placed upon ensuring that the first stories they hear are best adapted to their moral improvement” (378e).

In one particularly significant contrast, Plato juxtaposes polypragmasune (minding the deeds of others, or colloquially, sticking your nose into their business) with the fact that justice demands of each citizen to “do your job” (423d). No well-ordered polity can evolve without this imperative. It has different parts, however. First of all, it requires that people be given jobs for which they are well suited, a claim that rubs against our oft-stated but obviously foolish belief that any person can become whatever that person wants. Such a belief will result in rampant incompetence. Self-government, in both senses of that term, requires competency (455b) in a wide array of practices.

Competence being an essential element of “doing your job,” it must be accompanied by a sense of personal and civic responsibility. This sense of responsibility prevents both shirking and the exploitation of the job for purely personal benefit. The job must contain that element of service. Furthermore, “doing your job” means not trying to do someone else’s job, nor allowing someone else to do your job. No “good man” will tolerate being told what to do (425e). Pride in a job well done results from not having someone else do it for you, but it also means that you have protected your realm of responsibility from intrusion by another. Despite his recommendations for the education of the guardian class, Plato recognized that parents would resent intrusion by the polity into their prerogatives. The moral seriousness of this point is captured by the Catholic idea of subsidiarity.

Socrates asserts that, virtue being the most important thing, stories that celebrate vice and undercut virtue must be prohibited, for “a young person can’t tell when something is allegorical and when it isn’t."

A final observation about the dialogue brings us back to where we started, and that is, after hours and hours after intensive discussion, we have a pretty good idea of what justice isn’t, but no clear idea of what it is. At those moments where it becomes evident to the reader that Socrates can’t provide us with dogma concerning the nature of the good life, he resorts to mythmaking. Just like the conclusions to the Statesman and the Gorgias, the Republic ends with a myth of judgment in death that tries to persuade the listener that the life of virtue is to be preferred above all others. Such truth cannot be articulated in propositions but only discovered in the existential pull on the soul. The fact that justice cannot be turned into a set of propositions—and certainly not into slogans—will always frustrate those who cloak the desire for power in the robes of justice.

The American Republic

The prospects of justice in this world are grim. Like truth, it can be the possession of no person or movement. Its relationship to liberty is fitful, for as the latter expands, the claims of virtue often contract. When autonomy becomes our defining feature (557b), we rapidly devolve into lotus-eaters (560c), who “indulge in every passing desire that each day brings” (561c). Libertinism brings as its handmaiden egalitarianism (561e): each inconsequential person, in the words of Tocqueville, glutting his or her soul with petty pleasures. Plato contrasts this with “the competence and the knowledge to distinguish a good life from a bad one,” and “to weigh up all the things we’ve been talking about” in both their particularity and universality. Justice requires a person be attendant to particulars and circumstances, and learn how “to make a rational choice from among all the alternatives,” which the person must do “during his lifetime” (618c-e). This application of practical reasoning to the problem of justice, the attendance to both word and deed within time, marks the actual Plato as opposed to the “idealistic” version often given to us.

Nonetheless, Plato’s ideal state has troubled liberal thinkers, who find the Greek’s ideas too illiberal for their tastes. The quasi-communism involved in the education of the guardian class along with the censorious authority of the rulers unnerves modern readers. And while Plato gives us a guide for thinking about “public things,” it certainly isn’t a democratic republic to which he leads us. References to “the noble lie” and “the myth of the metals” and the “talk about the gods” all underscore Plato’s concern that no good polity can survive without a compelling principle of unity. Surely this is at the core of “the anthropological principle” whereby Plato analogizes the soul to the city, and indeed only talks about the city because it is “the soul writ large,” the central thing about which he wants to find the truth.

Plato’s efforts to get us to understand justice hinge on whether we accept the validity of the anthropological principle. Even if we live in an age of fractured personality, serious thinkers will recognize the need for an integrated self and realize that such integration requires a unifying principle that can harmonize otherwise disparate parts. Without an interest in such integration, we would be at a loss to describe why hypocrisy bothers us so. We regard a unified self to be a person of high character and a fractured self to be a good-for-nothing. Whatever criticisms we might offer of the anthropological principle, they don’t unsettle the self-evident truth established by a unified personality, nor would those criticisms undo our sense that, without some unifying principle, politics would soon devolve to war.

Contemporary criticisms of liberalism consistently miss the fact that liberalism is an effort to find some basis of unity in the middle of violent conflict and that, as importantly, such a principle of unity cannot be established by coercion alone. The liberal solution (to the degree that there is one) and its success rests on the clever hiding of a unifying principle as a way of making it less susceptible to dispute, and such obscuring is virtually required by the demands of freedom. In this sense, the liberal determination of the problem marks a serious advancement over the Platonic solution with its scant attention to freedom, a solution that becomes so impracticable that the principle of unity is contained and carried within the soul of the philosopher from where it radiates out into the order of the city itself. The philosopher has such “reverence” for this underlying principle that he will, Plato argues in “The Seventh Letter,” shrink “from putting it forth into a world of discord and uncomeliness.” But such is the world we inhabit. Our constitutional system is predicated on taking men as they are and not as we wish them to be, and this realism in turn operates, almost ironically, as a unifying principle. Rather than dreaming of a world without “discord and uncomeliness,” the framers of our Constitution attempted to create a system that could accept interest and passion as a feature of politics while acknowledging a mutual commitment to the common good as articulated in the Constitution’s Preamble. Neither were they quick to assume that the idiosyncrasies inherent in passion and interest were necessarily immoral. Instead of dismissing interest as inimical to unity, the framers of our Constitution believed that the divisions themselves could be turned to justice’s (and truth’s) advantage. This strategy of balancing unity and division (E pluribus unum) was at the heart of Orestes Brownson’s observation that American constitutionalism represented a great leap forward in the human understanding of ordered liberty, and that justice was best served not in the rule of the philosopher but in a set of institutional arrangements that could maintain freedom while acknowledging the need for energetic rule.

Consider here Publius’ defense of the Constitution as found in The Federalist Papers. In Federalist 9, Hamilton argued that the great innovation in the “new science of politics” that makes an extended republic possible was a deeper understanding of the principles of representation. Only by properly creating a system of representation could the Constitution stabilize the government in its vacillations between tyranny and anarchy, and also ensure that government retained its just powers in the consent of the governed. In other words, the establishment of justice involved the creation of governing institutions that derived their power from the people while at the same time restrained the popular passions that could devolve to anarchy or result in tyranny. Democracies always had to fear becoming either of these things—think of book 8 of Plato’s Republic (discussed earlier)—and while tyranny results from a surfeit of power, anarchy tended to result from an excess of liberty. Thus Hamilton, in Federalist 62, argued “that liberty may be endangered by the abuses of liberty as well as by the abuses of power” and insisted “that there are numerous instances of the former as well as of the latter; and that the former, rather than the latter, are apparently most to be apprehended by the United States.” This fear that liberty was a greater threat to justice than was the desire for power undergirded almost all of Publius’ reflections on the matter.

Madison, in Federalist 47–51, after having laid out the arguments for the distribution of power between the federal government and the states, and having identified the specific powers attributed to the federal government, turned his attention to the form of the federal government. The separation of powers between the legislative, executive, and judicial functions, he asserted, was an essential safeguard for the preservation of liberty. In Federalist 48, meanwhile, he argued that the powers of the different branches couldn’t be so separated from one another as to render the new government imbecilic. Furthermore, liberty was best protected not only when powers were separated, but when powers were shared by separate branches. Simply fixing boundaries in the text of the Constitution provided a mere “parchment barrier” that could not withstand power’s encroaching tendencies (or the effort to take over someone else’s job). The evidence of the inadequacy of these parchment barriers could be discerned in the tumultuous politics of the states where “the legislative department is everywhere extending the sphere of its activity, and drawing all power into its impetuous vortex.” In a democracy, Madison believed, the greatest threat of tyranny came from the legislative branch, not the executive or judicial, and so that was the one whose powers had most to be curtailed.

The establishment of justice involved the creation of governing institutions that derived their power from the people while at the same time restrained the popular passions that could devolve to anarchy or result in tyranny.

The inadequacy of written prohibitions led Madison to conclude that tyranny could only be prevented when ambition was made to counteract ambition, and that meant that “the interests of the man must be connected to the constitutional rights of the place.” In other words, by giving the members of each of the branches of government specific but also consequential powers, their interest in power would motivate them to resist the encroaching efforts of the other branches, and thus they had to be provided with the tools necessary to resist such efforts. Madison assumed that people in government possessed limited turf, and for that reason would zealously and jealously guard it. Thus the instituted systems would be effectively self-regulating. A dependence on the people remained the primary check on government, but experience, he observed, impressed upon us the need for auxiliary precautions. Taking men as they are and not as we wish them to be—and them not being, after all, angels—the lust for power could be placed isometrically in a system of mutual frustration. The private interest of each actor thus acted as “a sentinel” over the public good. These constitutional inventions, he argued, were dictated by prudence and experience. The demands of practical reason meant weakening the legislature while strengthening the executive. This division of power within the federal government, when combined with the principle of federalism, provided “a double security” against power’s tyrannical tendencies.

Here Madison connects the constitutional provisions to the paradoxical tension that lies at the heart of the republican system: On the one hand, the government had to rest on the consent of the people, but on the other hand the people had a tendency to oppress and vex one another, and would use the instruments of government as tools to accomplish such. In other words, the constitutional separation of powers might ameliorate the problem of government corruption, but it couldn’t mitigate the equally troublesome problem of faction. Surely that is what Hamilton was referring to in the aforementioned quote from Federalist 62, for Madison had already established in Federalist 10 that liberty is to faction what air is to fire, and the establishment of justice would require recognizing not only the threats that accompanied the formations of power, but also the dangers inherent in liberty itself, particularly as they manifested themselves in factions.

“There are,” Madison wrote, “but two methods of providing against this evil: the one by creating a will in the community independent of the majority that is, of the society itself; the other, by comprehending in the society so many separate descriptions of citizens as will render an unjust combination of a majority of the whole very improbable, if not impracticable.” In short, only by the fracturing of society itself could the security against faction be realized, and this fracturing represented moral progress over insistence on unity that either mirrored Plato’s educative state that gave everyone the same opinions, or its anticipation in the Progressive claim that unity could be achieved by transforming human nature. That fracturing, in turn, could be accomplished by different means, and indeed in many mays existed naturally, but in any case would result from liberty. By ensuring that people had a right to think freely, to worship according to the dictates of their conscience, to associate with one another on their own terms, to prefer the well-being of their localities to that of other places, and to allow for the natural proliferation of discrete and particular interests among the different classes that composed society—in other words, the free exercise of our natural tendencies as human beings—the dangerous ascendancy of any one faction or combination of them could be mitigated. Institutions in a federal system, operating out of the extended sphere, thus rendered factions impotent while allowing freedom to flourish. By decreasing the dangers of faction without imposing a unifying principle, the constitutional system could simultaneously decrease the need for more powerful national governing institutions.

We will take to the streets demanding justice, but no one holds placards calling for prudence.

Madison intentionally juxtaposes his solution to the strong-armed efforts of Socrates that resulted in “noble lies,” repression of false “talk about the gods,” the eviction of the poets from the city, and the rule of the philosopher king. Instead, we live in a world where “enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm” and, in the public realm, even if every person were a Socrates, every assembly would still be a mob. Nonetheless, Publius balanced the agonism of factional politics with the conviction that Americans remained unified by common experiences, commitments, and beliefs—in short, a common culture whose capital could not be spent down without replenishing it, an idea to which Washington testified in his farewell address. The threatening feistiness of our contemporary politics reminds us of both the need for a principle of unity as well as the dangers inherent in locating that principle in a particular person or faction.

Justice as Threat

Understanding the nature of this delicate balance, Madison offered in Federalist 51 this fascinating observation: “Justice is the end of government. It is the end of civil society. It ever has been and ever will be pursued until it be obtained, or until liberty be lost in the pursuit.” Why would liberty be lost in the pursuit of justice? What is it about justice that makes it a potential threat to liberty? Let me suggest various reasons why this might be the case.

First, of the four cardinal virtues, justice is the one that admits of the most confusion, as we saw in our discussion of the Republic. This makes justice peculiar among the four cardinal virtues. We have a pretty good idea what courage and temperance and prudence are, but the essence of justice eludes us. This nebulous quality makes it capable of producing prodigious and dangerous errors in its name. It’s in the nature of prudence and temperance that we can’t really be mistaken in our exercise of them, and while we may be mistaken in our exercise of courage, perhaps only once. But justice seems to admit of infinite error when we act in its name.

This indefinite nature is in part why justice admits of appending endless qualifiers. We know about distributive and retributive justice, procedural and restorative, but we also now hear of racial justice, environmental justice, criminal justice, sexual justice, and so forth. It wouldn’t make much sense for us to talk about racial courage, or criminal prudence, or environmental temperance. We will take to the streets demanding justice, but no one holds placards calling for prudence. The desire for justice inflames our passions in a way the other virtues don’t, and it also seems to connect directly to our interests. Indeed, we too often dress our naked interests in the cloak of justice.

One cause of confusion is that justice is a relational virtue, whereas the other three cardinal virtues refer primarily to the self. I am temperate or I am courageous; but justice refers to the ways in which persons relate to one another or to the whole. A statesman may be courageous or temperate, but we expect a regime to be just. The relational aspect of justice is testified to by the fact that we react strongly to breaches of fairness. It’s one of the first things we learn as children. Few things upset us more than the sense that something isn’t fair, and that experience of being upset often results in bitterness and resentment. Freud, for example, noted that the religious impulse emerged largely from the anger we feel from living in a world where the evil are rewarded and the good are punished. We created the idea of an afterlife, he argued, simply to satisfy our sense that good should be rewarded and evil punished, and the final judgment, sorting that all out, is where justice gets resolved. People will finally get what’s coming to them.

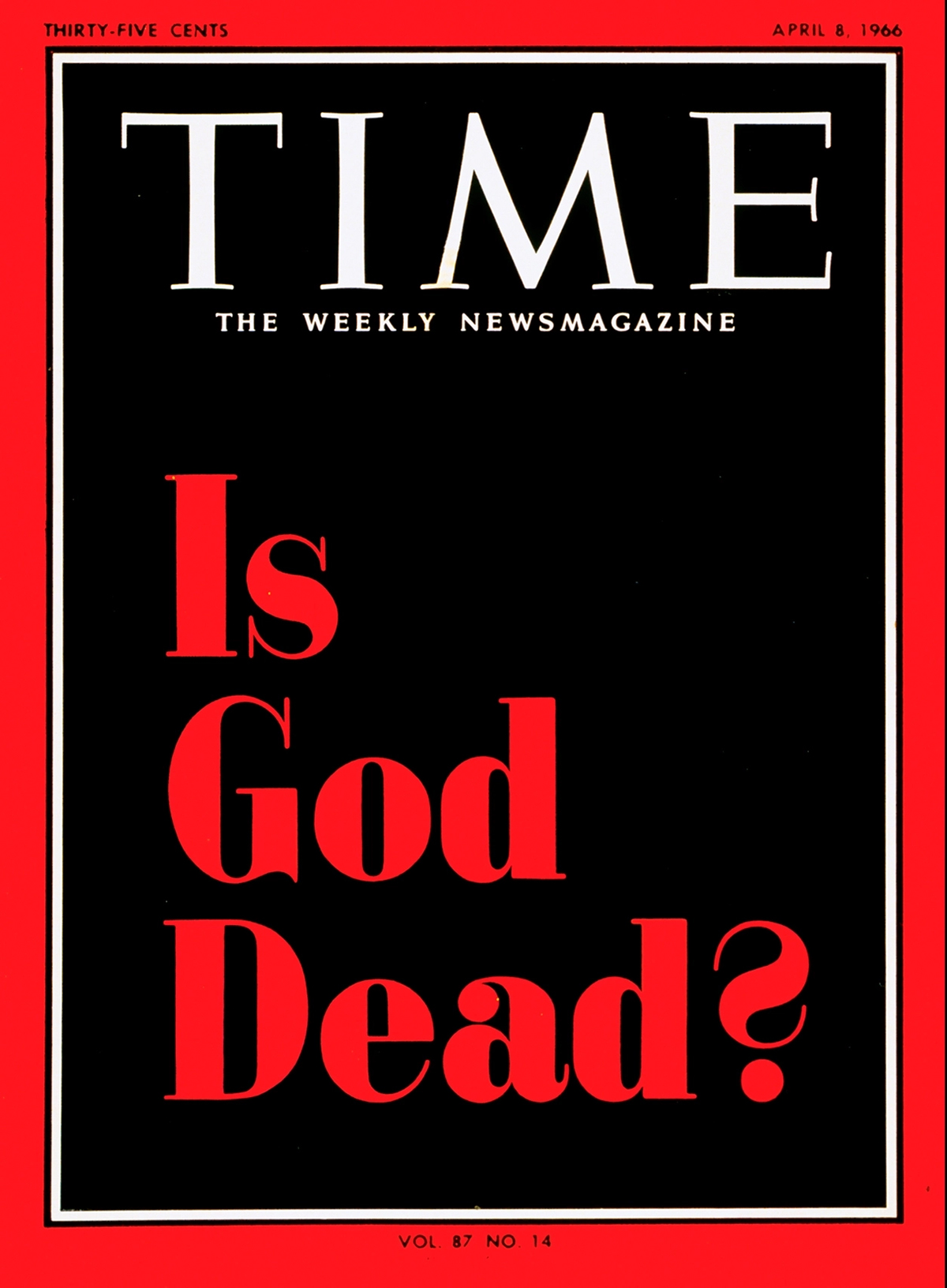

This draws our attention to the fact that justice has an important restorative function. Not only when harmony and balance are disrupted, but when our moral sense has been violated in some way, justice comes to the fore and demands that things be set right. Thus clemency is part of justice. In Federalist 17, as well as in his meditations on the pardoning power in Federalist 74, Hamilton directly connects the two to each other. Justice without grace soon becomes embittered and resentful. Nietzsche observed that, God being dead, we now had to baptize ourselves into our own clemency, invent our own rituals and sacred games. “Justice!” Nietzsche wrote, “I’d sooner have people steal from me than be surrounded by scarecrows and hungry looks; that is my taste. And this is by all means a matter of taste, nothing more.” Nietzsche thus demonstrates that the idea of justice can’t survive the acids of subjectivism and relativism. Even more damningly, Zarathustra admonishes his disciples to “mistrust all who talk much of their justice! Verily, their souls lack more than honey. And when they call themselves the good and the just, do not forget that they would be pharisees, if only they had—power.”

This pharisaism has become a central feature of our politics, and it characteristically refuses to accept disagreement as a condition for knowing: the Pharisees (and I’m using the term in its pejorative sense) convinced as they are that they already possess the fullness of truth and understand clearly the demands of justice—such conviction having been long ago undone by Socratic ignorance, and warned against by Publius. Whatever else is true about campus and communal battles over social justice, one would have to be willfully blind not to see how the grasping for power drives the enterprise. But such grasping for power should not lead us to the conclusion that there is therefore no underlying moral impulse. This is the great danger of our time: an unwillingness to see in our opponents some reaching for a moral truth and our concomitant inability to consider we might be wrong.

Part of the problem is that certainty renders politics sterile and predictable. Consider, for example, debates that consumed the country following the death of George Floyd. Tell me how someone voted in the 2016 election and I’ll tell you exactly how they reacted to news of Floyd’s death. I’ll go even further and tell you whether they consider Ron DeSantis guilty of a “gay ban” or whether he is sensitively responding to the moral demands of parents. In all instances, the system of mutual frustration set up by our Constitution gets undone by the pincer effect of impatience and conviction, an effect exacerbated by the hothouse of our corrupted media environment. We have all become philosopher-kings and have no need of restraints. As a result, injustice will disguise itself as justice; immorality as morality; repression as tolerance; uniformity as diversity. Behind it all is the imposition of will.

Surely part of our cultural battles involve our tendency to substitute a principle of unity for the unsettling agonism of our constitutional system. But here is where the difficulty resides. When Tocqueville noted that religion was the first among our democratic institutions, he referred to it not simply in a formal sense, but in the sense that underneath all the roiling turmoil of democrat life, religion provided a stabilizing influence that could rein in democracy’s excesses. Religion, he believed, was the bit in the mouth of the democratic horse that might enable us to guide and restrain democracy’s spiritedness, to “tame the democratic beast.” But would the horse chew up the bit, and if so, what might take its place to keep democracy from careening over a cliff?

Tocqueville rightly expressed concern that, without true religion, Americans would settle on either a false one or would devolve into a dogmatomachy (war of ideological certitudes). This battle would intensify as the underlying cultural consensus collapsed. Competing groups would thus seek to impose a particular version of “their truth” as “THE truth.” Indeed, debates over our founding myths (1619 or 1776?), Catholic integralism, and “wokeism” reflect efforts to replace America’s largely hidden religious self-understanding with a new set of myths. The philosophical project of the day, therefore, reflects that of Plato: to expose false talk about the gods while at the same time restoring intellectual humility to its rightful place. It seems to me that Madison was on the right track. The falseness of the woke religion is testified to in no small part by the viciousness of its tactics: its deplatforming, its canceling, its intolerance, its absence of humor, and its violence in the streets. Its justice is a harsh and unyielding one, separating sheep from goats. The absence of charity is not a bug but a feature, as it will be of any god that fails. In that sense, devotees of true religion may serve like Elijah, mocking the priests of Ba’al as they perform their empty rituals while testifying to the true God in simple acts of faith.

Our obsession for justice can close us off to what is good. This relates to Madison’s point, I think, in Federalist 51: There “liberty” refers to the institutions of representative, divided, and federalized government, and when people become consumed with the demand for justice, they will destroy those institutions rather than live in a world they think imperfect. The demand for perfect justice will result in the worst kinds of injustice.