In a profile for The Guardian from 2012, Kim Kardashian was perplexed. “When I hear people say [what are you famous for], I want to say, ‘what are you talking about?’… I have a hit TV show. We’ve shot more episodes than I Love Lucy!”

In the wake of multiple scandals that have rocked the evangelical world, from Mars Hill to Hillsong, the role of the celebrity pastor has come in for intense scrutiny. Why be faithful when you can be fabulous?

By Katelyn Beaty

(Brazos Press, 2022)

Emma Brockes, the journalist who wrote the Guardian profile, was just as perplexed as Kim. She spends most of the 3,000-word essay trying to make sense of why her star was on the rise. She finally asks directly:

“What is my talent?” [Kim replies.] She cocks her head to one side. “Well, a bear can juggle and stand on a ball and he’s talented, but he’s not famous. Do you know what I mean?”

This might be the perfect distillation of what it means to be a celebrity in the 21st century. In many ways, Kim was the trailblazer—a star of the reality-TV era who successfully expanded her influence into not only fashion, television, and film, but also law, politics, and as of April of 2022, private equity.

That model of influence has a deep history in American culture, with parallels in the church, and understanding its impact on evangelicalism is the subject of Katelyn Beaty’s new book, Celebrities for Jesus: How Personas, Platforms, and Profits Are Hurting the Church. She distinguishes celebrity (what Kardashian enjoys) from fame as understood in previous eras. Fame “is a by-product of virtue, the effect rather than the goal of living a virtuous life.… It is at its finest when it comes to those who are not seeking it.” Celebrity, on the other hand, is defined not by great deeds or virtue but rather by the “celebration” of an individual. “It’s similar to fame,” she writes, “but doesn’t require doing anything of particular importance, talent, or virtue.”

To translate Kardashian’s comments into Beaty’s framework, the juggling bear might actually be famous, but Kim is a celebrity.

Beaty has written a book that manages to be both thorough and concise, providing an impressive overview of evangelical celebrity with a blend of journalism, cultural criticism, and pastoral theology. Readers will walk away not only with a sense of the phenomenon’s history and problems but also the seeds of how pastors might reimagine their role in the modern church.

America’s Pastor?

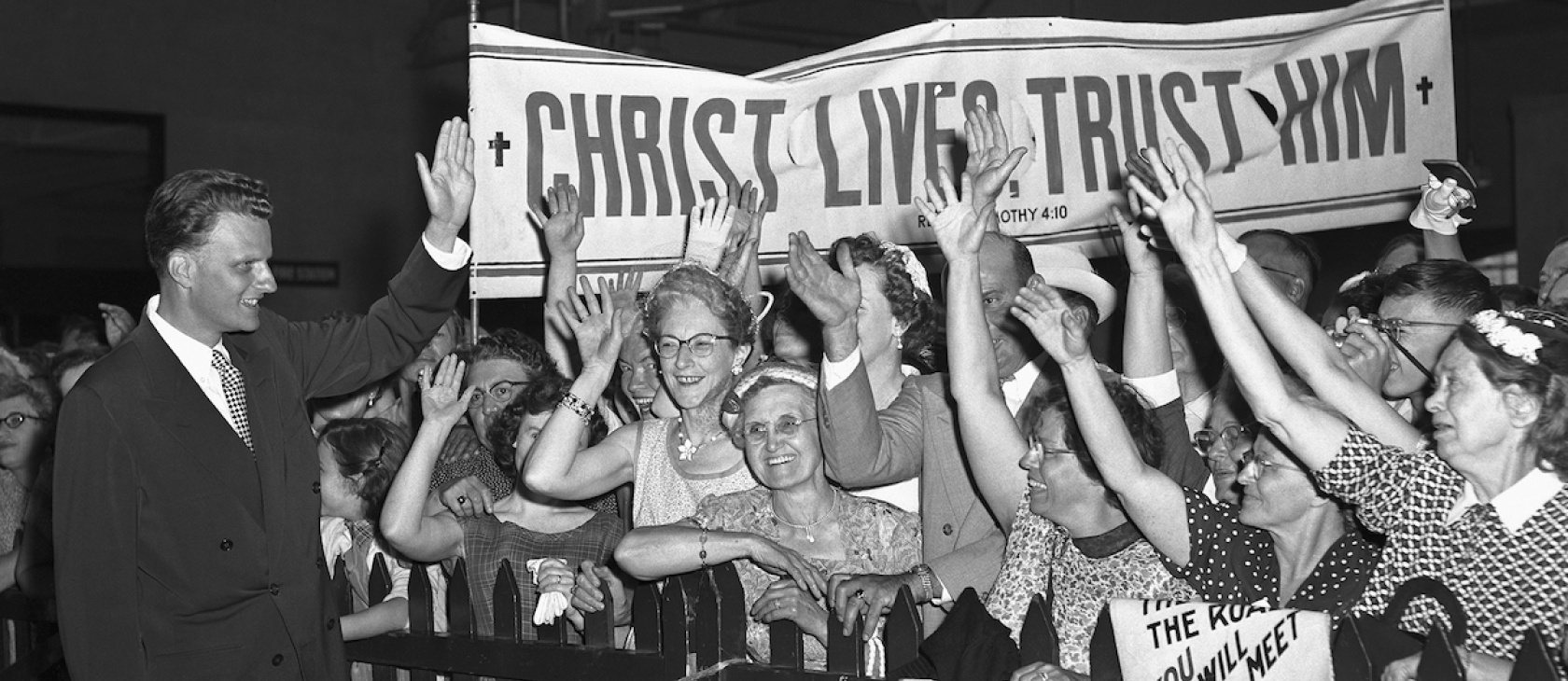

Beaty’s treatment of Billy Graham illustrates the care she takes to tell this story soberly and fairly. Graham was the first and most significant evangelical celebrity and deliberately chose mass media as a tool for ministry, wielding authority with what Beaty describes as “charisma, passion, and communicative power.” He was eminently watchable, with a rugged all-American handsomeness, a dash of Southern charm, and above all else, a profound sense of earnestness and urgency. Graham didn’t want your money; he wanted to make sure you didn’t go to hell.

His ministry avoided most of the pitfalls that would sink future Christian celebrities, but Beaty cites Neal Postman’s observation that his embrace of mass media was an indicator of “gross technological naivete.” His reputation as “America’s Pastor” is a significant example of how much he transformed our spiritual imaginations. Beaty writes: “America’s Pastor isn’t quite the right name for Graham. A pastor is a shepherd of souls, and to shepherd a soul, you have to know a soul.”

But she also notes important ways Graham distinguishes himself from much of the celebrity culture that followed. He worked with local churches, funneling converts into communities that could shepherd them. He formed a board that set his salary and committed to never exaggerate attendance or conversion numbers. And, perhaps most importantly, he invested in institutions “that didn’t need or depend on his gifts or charisma to succeed,” including the National Association of Evangelicals, Fuller Theological Seminary, and my own employer, Christianity Today.

“Graham saw with prescient wisdom how intoxicating it would be for leaders to believe they are so important they can evade the accountability they need,” Beaty writes, “even and perhaps especially when their work seems crucial for the kingdom.” As much as the word evangelical has been distorted, she says, a character like Graham makes abandoning it altogether difficult. When asked if the label applies to her, Beaty answers, “It’s complicated… If an evangelical is defined as ‘anyone who likes Billy Graham,’ as biographer George Marsden famously quipped, I guess I’m in. I quite like Billy Graham.”

She maintains a sense of affection for the evangelical movement throughout the book, which is no mean feat at a time when many of the incentives lie in the direction of writing a jeremiad. I felt that pressure while reporting and producing the podcast The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill and received no small amount of criticism for refusing to throw specific theological tribes, evangelicalism, and even Christianity itself under the bus. Doing so would have simplified a problem that is much more complex. I found myself thinking often of Hanlon’s law: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.” To expand that a bit, there is a difference between malevolence, foolishness, and thoughtlessness, and much of the weirdness of evangelical celebrity culture—including some of its corrupted attributes—belong to the latter two.

Billy Graham didn’t want your money; he wanted to make sure you didn’t go to hell.

“Celebrity … is a worldly form of power and evaluation of human worth,” Beaty asserts. “It is not a spiritually neutral tool that can be picked up and put down, even for godly projects. The moment celebrity is adopted and adapted for otherwise noble purposes—sharing the good news and inviting others into rich kingdom life—it changes the project. And it changes us.” Matthew Crawford’s concept of cultural jigs is helpful here. These are structures of ideas and incentives that form desires and behavior. They operate without much thought or active participation, which means they are incipient and dangerous. The cultural jig that inclines one toward celebrity gave us Kim Kardashian. It also gave us Carl Lentz, the fallen pastor from Hillsong New York who in addition to having committed adultery has been accused of all manner of spiritual abuse.

Similarly, the jig that formed him has formed hundreds of imitators in churches across the country—men and women (though mostly men) who might not have the same malevolent inclinations as Lentz but have come to believe that embodying an influencer image is the best way to reach their neighbors for Jesus. If that’s the case, their error isn’t narcissistic self-indulgence; it’s a failure to think and judge.

This is why Beaty’s book is so necessary and why her tone of familial affection is so helpful. By not taking an outsider’s stance or shouting, “Burn it all down!” she makes bridge building possible and presents herself as a concerned guide that might help wrongheaded leaders to “think what we are doing” (to borrow Hannah Arendt’s phrase).

The Weirdness of Evangelical Culture

The book concludes with a few directional ideas for leaders who want to avoid celebrity culture’s errors or bring reform. One of evangelicalism’s mistakes from the very beginning was grandiosity, and it strikes me as dangerously tempting to address at this moment even more of it—demanding the church “burn down” or “gouge out” the trappings of celebrity and entertainment in ways that both indulge a grandiose spirit (“We’re the new reformation!”) and lack realism. They remind me of parents shouting at their children to eat their broccoli; they might get them to do it, but they won’t get them to love it.

Beaty, however, emphasizes spiritual formation and spiritual friendship, pursuits that can’t turn the ship overnight, but that’s precisely the point. Change is likely to be small, slow, and local. Mustard seeds, not spectacles.

I found myself laughing at many points while reading the book. Beaty was developing her project in parallel with my own Mars Hill, and without ever talking about it or comparing notes, we ended up covering many of the same historical inflection points and problems. As I reflected on Beaty’s book, I found very little to disagree with, but several ideas that I think need deeper consideration for the sake of the church.

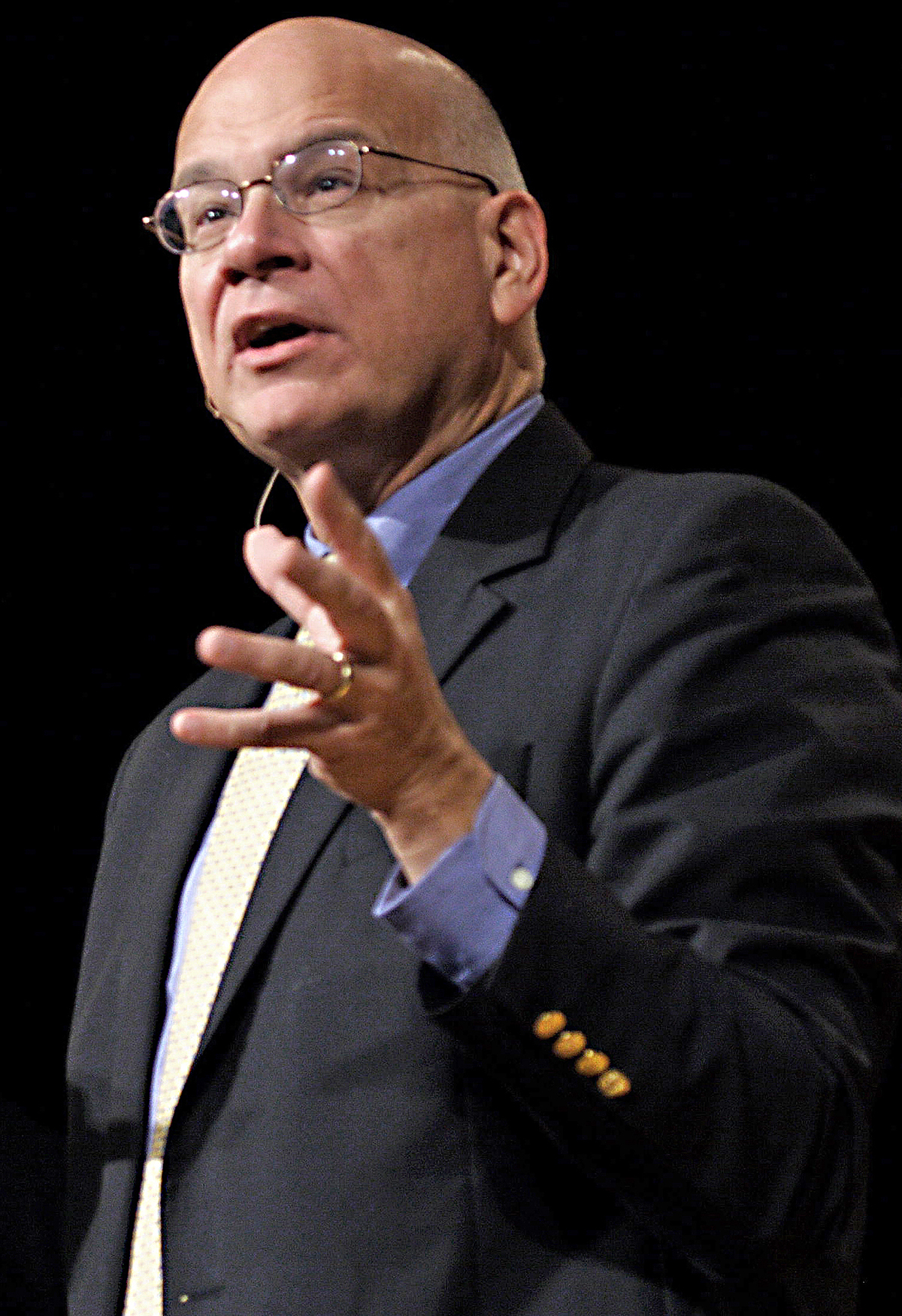

One is the phenomenology of celebrity. Evangelical culture is weird in part because American culture is weird, and success in almost any work in the public sphere will result in some degree of celebrity. Tim Keller, founder of Redeemer Presbyterian Church, is an interesting case study. He was influential for a long time inside a small circle of Presbyterians and church planters, but in the mid-2000s, a post-9/11 attentiveness to New York City, a church-planting boom, and a neo-Calvinist movement expanded that circle to a global platform. Today he’s one of evangelicalism’s most well-known figures.

We need to reinvigorate the role of institutions in the church, and that may mean revitalizing and empowering denominations.

In Celebrities for Jesus, Beaty distinguishes celebrity—the ability to sustain “celebration” in the public sphere—from fame—the renown that comes from virtue or meaningful contribution to the common good. Keller’s appearance in the public sphere is certainly due to the latter, but today he experiences many of the trappings of the former. If he walks into certain rooms, he will get mobbed by fans who want him to sign books and take pictures. Celebrity wasn’t something he pursued, but rather it happened to him.

I’m also interested in the need for institutions in any efforts at reform. Beaty connects Yuval Levin’s work to her own—how weakened institutions have lost their ability to form their constituents, instead becoming platforms for celebrity. (One might say they no longer function as the cultural jigs they once were.) One significant piece of evidence is the prominence of nondenominational evangelical megachurches, which make up the majority of growing churches in the U.S.

An important thread in The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill was the way that church shifted its bylaws over the years, moving the center of power so that it gave Mark Driscoll an increasingly free hand and softer accountability. By contrast, Billy Graham (as Katelyn Beaty points out in Celebrities for Jesus) invested in institutions from which he enjoyed no benefit. Moreover, as his ministry became more influential, he established institutional safeguards around it and submitted to them. It seems to me that we need to reinvigorate the role of institutions in the church, and that may mean revitalizing and empowering denominations, or it may mean establishing new institutions—ones that actually function.

Lastly, I think we need a deeper exploration of the role of the inner life in these conversations. There’s a great deal of literature on the psychological aspects of this phenomenon in churches, and Beaty touches on one of the better ones in her discussion with Chuck DeGroat, author of When Narcissism Comes to Church. But to borrow from Charles Taylor, we need to understand the extent to which the disenchanting effects of modernity have closed off spiritual experience and communion with God, sending us in pursuit of meaning within the world.

The Perils of the Impoverished Inner Life

In Celebrities for Jesus, Beatty references what is one of my favorite explorations of the subject: a 1975 speech by Hannah Arendt, given in acceptance of the Sonning Prize.

For as much as she was a public intellectual, Arendt did not consider herself a public figure. She wanted her work to speak for itself; by winning the Sonning Prize, she was stepping into the public sphere in a way that was deeply uncomfortable for her.

The entire speech is extraordinary. In it Arendt describes how life requires us to put on personas, performing as it were the roles assigned to us—mother, father, teacher, doctor, husband, etc.—not because any one of them is necessarily false, but because our nature is much more complex than any one of them. We appear in these roles, but they do not and cannot express the whole of who we are, and certainly not our inner life.

This strikes me as one of the most essential challenges for Christian leaders. Arendt was uniquely attuned to the ways modernity had impoverished the inner life, as well as the premodern resources that once invigorated it. Her Ph.D. thesis was about love in the work of Saint Augustine, and in an essay called “Augustine and Protestantism,” she describes how one of the great contributions of The Confessions was that it opened up the “inner empire of the soul.” Augustine gave readers a way to think about their thinking, their inner conditions, their desires and wants. Modernity turned the lights out on that inner realm, sending individuals out into the world in search of other sources of insight and meaning.

For Arendt, this impoverished inner life is at the root of much of the 20th century’s evil; robbed of the capacity to look inward, we find ourselves also incapable of thinking and judging. It is a short trip from the loss of thought and judgment to participation in atrocities—be they mass genocide (her primary topic) or enabling spiritual abuse (the topic I’ve been devoted to for several years). Like the problem of celebrity, we find ourselves dealing with a phenomenological reality: The world we live in forms people in this way. But unlike reforming the problem of celebrity, reinvigorating our inner life isn’t out of reach—especially for a church with a rich heritage of contemplative practices.

There are direct implications that flow from this to the practices of evangelical churches, especially evangelical worship services. There is prescience in James K.A. Smith’s description of megachurch gatherings: a Coldplay concert followed by a TED talk from “the smartest guy in the room.” The description fits well with Beaty’s work—these gatherings create an artifice of celebrity even inside the closed system of an individual church, and perhaps they’re effective because celebrity itself feels transcendent.

Renewal and Innovation

If evangelicalism is to experience renewal in the years to come, it will have to reckon with the ways it has been enculturated and oriented around celebrity, and Beaty’s book is an essential contribution to the conversation that needs to happen. And as much as we might critique evangelical culture, there is much in its history and practice worth mining—especially its spirit of innovation. So while we need to reach into the broader church’s tradition, looking for practices that can invigorate the inner life of our communities, we also need the resources of our own tradition to find fresh language and fresh ideas for embodying them.

We need to awaken to the devastation that has been left in the wake of the evil, foolishness, and stupidity of the past several decades, and I think Beaty’s book is an important contribution to that end. My prayer and hope is that on the other side of that awakening, we can remain both sober and affectionate as we seek renewal. As Cormac McCarthy put it in The Road, “When one has nothing left make ceremonies out of the air and breathe upon them.”