Saint Augustine famously wrote about the existence of two cities traveling together through time and space on earth. One is the city of man. The other is the city of God. The Christian must live in both and find a way to live faithfully amid the inevitable tension. Early Christians experienced this tension in dramatic fashion. We feel it today, too.

Part of the church’s history has to do with periods of intense persecution and martyrdom. Steven D. Smith’s recent book, Pagans and Christians in the City, relates the incredulity pagan Romans had when faced with the intransigence of Christians. The fundamental difficulty was that the pagans could not understand a conflict between the power of the state and the power of God. Pagan religion was not concerned with searching inquiries into the nature of truth. There are no doctrinal battles in paganism. Rather, pagan religion is simply performative in nature. It involves giving a sacred glow to both nature and institutions through public ritual. In this regard, the Romans considered themselves tolerant and enlightened. The Christians, like everyone else in the empire, could incorporate their Jesus into the broader pantheon of gods. And while they were at it, they could do what everyone else did, which was to render the necessary public performance. It did not matter if they believed it in their hearts; they simply had to say the words or perform the actions. However, they could not. They could only affirm that Jesus is Lord. With that statement came the spoken or unspoken corollary that Caesar is not.

This refusal of Christians to cede authority over essentially everything fit with the teaching of Jesus in Mark 12:13-17. In that passage, we see Jesus questioned about paying taxes to Caesar. He answered that one should render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s and unto God that which is God’s. There are at least a couple of important conclusions we can draw from this answer. First, Caesar (the secular government) has a legitimate zone of authority. There is an important task to be done by the government in restraining sinful actions and punishing wrongdoing. But second, we must recognize that Caesar’s reign is not coextensive with God’s. He is not God, cannot be God, and must never demand from us what only God justly can, which is obedience and submission at the most fundamental and essential level. That simply does not belong to human government, which rightly wields a more modest authority.

Because of the Sermon on the Mount’s emphasis on turning the other cheek and eschewing violence, many early Christians doubted that they could serve as soldiers or policemen. They were willing to pray for the city and to be exemplary citizens in most ways, but they believed the sword was forbidden to them. Martin Luther answered in a way that remains edifying. It is certainly true that we must not strike back when struck and that we should quickly forgive offenses, but there would be little love or virtue in taking such a pacifist approach when watching one’s neighbor being killed or beaten. Luther noted that we feel obligated to love our neighbor by giving them food or water if they need it. We should also recognize that our neighbors need safety and order within which to try and live peaceful lives. It is for this reason that God gives us government and obliges us to respect and obey it. Its work is essential work. Per Luther, no Christian should refuse to participate in it, if there is need and he has the capacity to serve.

“As Christians in the United States, we have been given something extremely valuable: citizenship in a free country. With that right comes the corresponding responsibility of stewardship.”

Yet even now we struggle at times with questions such as these. The legendary American soldier-hero of World War I, Sergeant Alvin York, originally refused to serve, because his Christian scruples against killing were so great. It is good and right for us to regularly evaluate the dictates of Christian conscience over against the requirements of the state. That tension returns regularly and should never be too easily resolved or ignored. We should be attentive to the question at all times.

To this point, we have mostly dealt with the matter of Christians living in tension with the power of government. But there is another angle to consider, which is Paul’s strong statement in Romans 13 that everyone should be subject to the governing authorities and should not resist them lest they be found resisting God. Given that Paul himself died in prison, we should probably not find it hard to understand that his comments are not meant to be taken as an unlimited license for government authority. However, we still must deal with this very strong recommendation to “be subject.”

In the pre-democratic era, most human beings were indeed “subjects” rather than citizens as we recognize the term today. For the most part, they were acted upon rather than acting through the mechanisms of representative government. In other words, they typically did not have a choice about what the government did, unless they wanted to mount some kind of revolt. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that some Christians viewed government as simply something to be endured, like the weather. What they viewed as important was their spiritual lives in the church. It is interesting that the American Revolution against the British empire took place after the spiritual revolution of the First Great Awakening, in which many began to see themselves in direct connection with God rather than meeting Him only through institutional hierarchies.

We could do another essay on how the Western world moved toward democracy and human rights, but for now it may suffice simply to make the point that the broad scope of citizenship, with its various rights and duties, owes much to the influence of Christianity. It is not a giant leap to go from acknowledging that all human beings are made in the image of God to the realization that we are common inheritors of the gift of reason who deserve to rule ourselves or be governed by our consent.

So, what is the duty of a Christian in a nation like the United States? We are clearly not merely subject to the government. Rather, we share in its sovereignty, the exercise of which depends on our consent. In the American context, we are indeed citizens. In fact, we are a nation that likes to think of itself in the way Aristotle recommended, which is as a middle-class oriented society, filled with people who have experience both in leading and following.

It is here that another passage from Scripture comes to mind, which is the Parable of the Talents in Matthew 25:14-30. In that story, we learn of the three servants who are given varied resources to safeguard in their master’s absence. Two of the servants take what they have been given and invest it, thus returning the principal and adding the increase. One fears his master and buries the talent, which he returns, unenhanced, to the master. The master praises the first two servants and invests them with further resources. But the third servant receives criticism and will not be trusted with more.

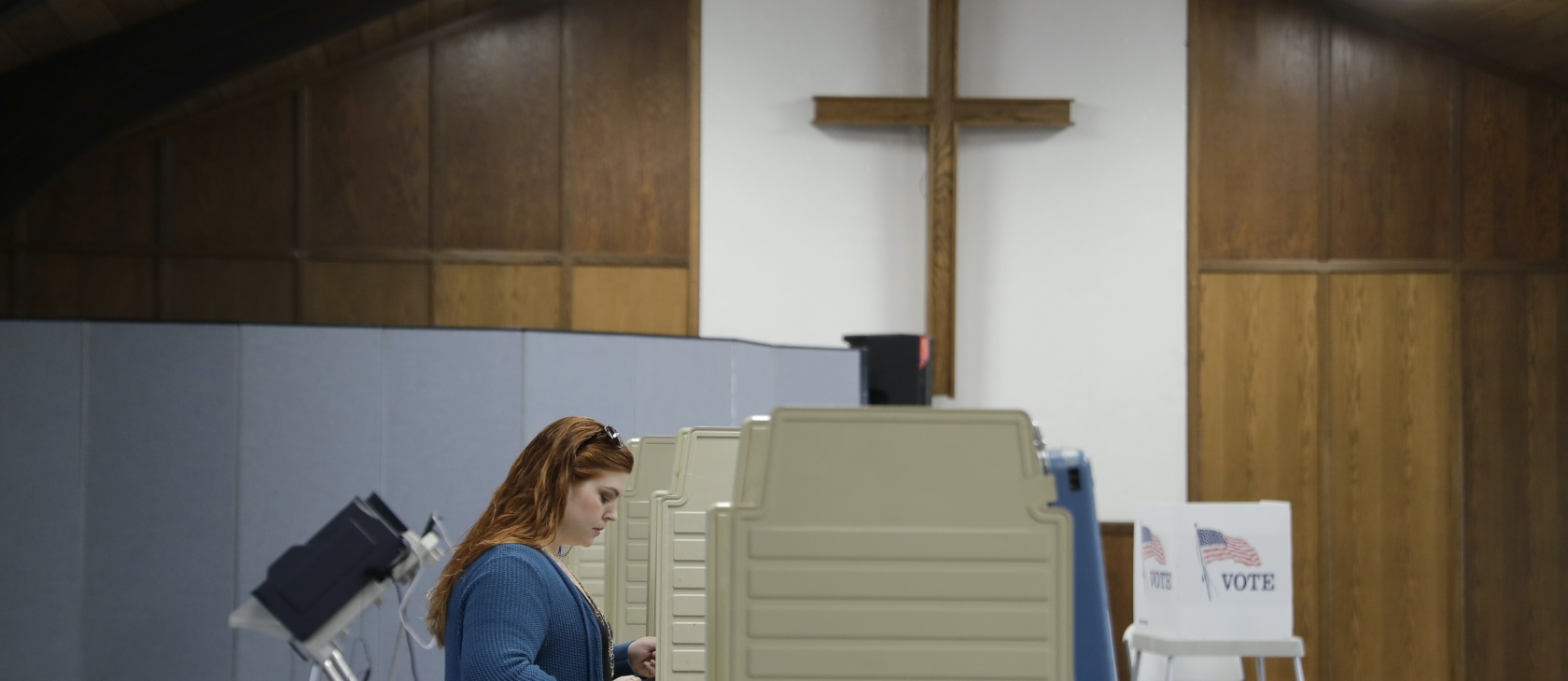

While the primary impact of the passage does not relate to citizenship, I think the logic is easy to extend. As Christians in the United States, we have been given something extremely valuable: citizenship in a free country. With that right comes the corresponding responsibility of stewardship. What will we do with this great boon of self-government? It would be foolish, short-sighted, and ungrateful not to make the most of it by educating ourselves and then participating fully. We have been given various levels of talents and abilities to organize, debate, run for office, judge disputes, etc., but we have all been given something we can put to use in our capacity as citizens. Do not simply endure the government. Instead, approach it as an object of stewardship. We are responsible for using the rights we have.

I would conclude with one caveat: It is not enough to merely be active, but one must be active in ways that are both wise and faithful. Alexis de Tocqueville was impressed by the democratic way of life he observed in America when he visited. However, he also detected a significant problem. Heady with the spread of democracy and the empowerment that comes with it, Americans ran the great risk of confusing the wishes of the majority with righteousness. As we exercise the awesome stewardship of citizenship, we must be ever mindful that the zone once occupied by Caesar – and now occupied by us – is subordinate to God’s greater reign. So, let us be sober, thoughtful, and mindful of our own fallen nature as we participate in the power of government. And most of all, let us remember that Christ is the King.