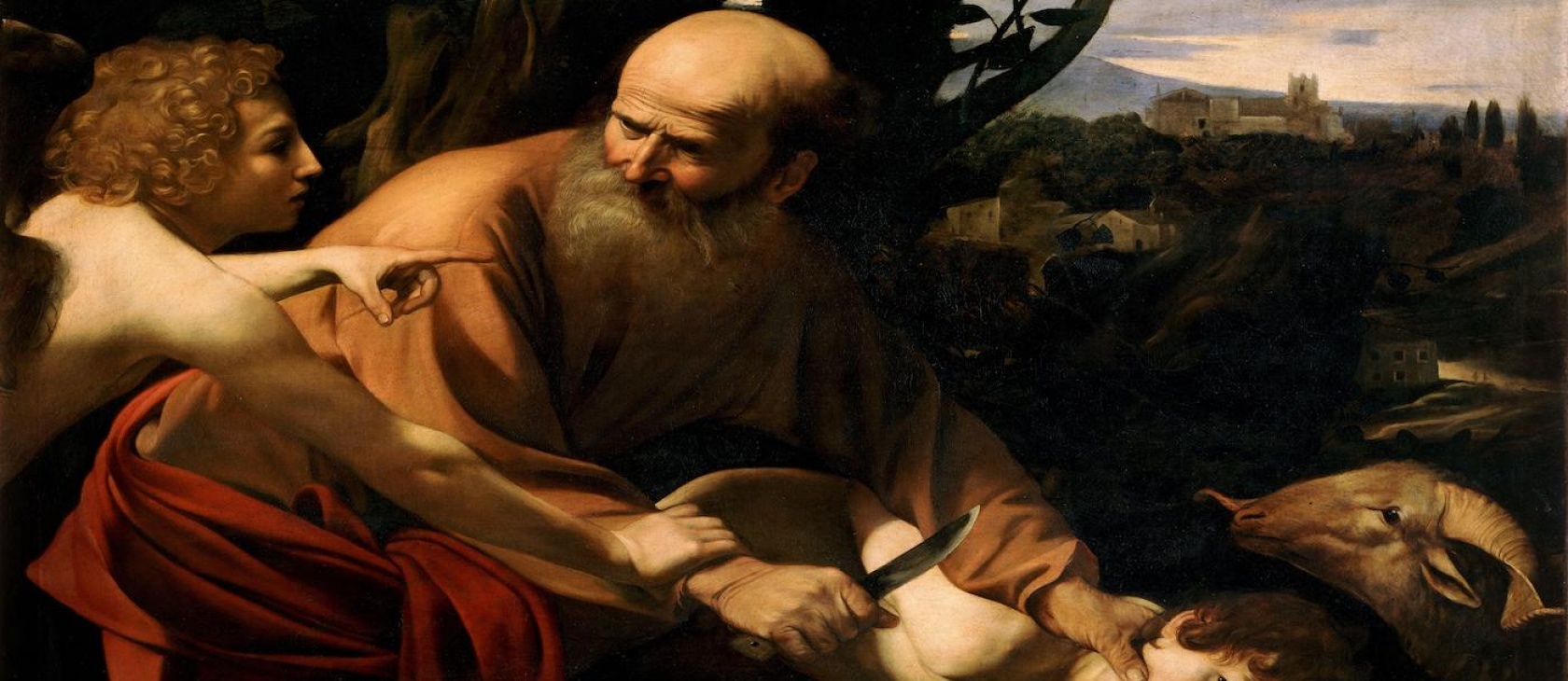

V’ha-elokim nisah et Avraham – four words in Hebrew; three in English: “God tested Abraham” (Genesis 22:1).

These three words begin the story of Abraham’s binding of Isaac. I just had the privilege of teaching this text, on the subject of sacrifice, to 20 exceptional middle schoolers, and they got it. Sacrifice is always self-sacrifice. But what does it mean to sacrifice yourself? If you want to understand the meaning of self-sacrifice, you don’t have to look far in the age of COVID.

On the words, “God tested Abraham,” the modern commentator Rabbi Joseph Dov Soloveitchik states:

The Master of the Universe did not enact the test of the Akeidah [the binding of Isaac] in order to discover the extent of Abraham’s self-sacrifice or his level of belief in and love for his Creator. This was all evident to God from the start. Rather, he wanted Abraham to reveal to the entire world, including himself, just how much he cleaved to the Creator. Until the trial of the Akeidah, the extent of Abraham’s commitment was hidden even from Abraham himself. Only on Mount Moriah did Abraham recognize and see himself in a new light: it was there, on the mountain, that he became aware of his enormous self-sacrifice and trust in God. This type of realization … demands self-recognition and self-knowledge.

Mount Moriah is the place in which Abraham becomes aware of his “self-sacrifice.” Prior to that, something was hidden from Abraham: his “self.” On Moriah, he “sees himself in a new light”—in fact he names the place Adoshem-Yireh, which Robert Alter translates as, “On the mount of the Lord there is sight.”

In Your light do we see light (Psalm 36:9)

Visibility is the classical Greek metaphor for intelligibility, as in Plato’s images of the sun, the divided line, and the cave—or in Aristotle’s Ethics, Politics, and other writings. Rabbi Soloveitchik speaks of “self-recognition” and “self-knowledge,” an intelligibility of the self to the self that is the fruit of “self-sacrifice.”

And what is it that you see, or recognize, or know when you see yourself in an act of sacrifice? You see yourself as a part of nature but also as something that transcends nature—a natural body but something else, too. The natural body is a part of a larger whole. The Bible does not refer to this larger whole as “nature,” or physis, as a classical Greek might. But even we naturalists—those of us who believe that nature is a whole, an order of things, of which the human is a part, a mammal with a special kind of consciousness—even we recognize that something more is at stake in this story, in which a God Who speaks to man from outside of that order appeals to the part of man which, too, is outside of that order.

The human face, as the late philosopher Roger Scruton said in his 2010 Gifford lectures, is a natural object pointing to something beyond nature. God’s call to Abraham is a call from beyond nature to that part of man which is beyond nature. It is the image of God that I see there, in your face and in my own.

This, indeed, is what self-sacrifice reveals. It reveals the soul of man in dialogue with God, an “I” and a “Thou” that speak intimately across an infinite distance—and yet, they speak. It is a speaking akin to natural speech but beyond it. It is a speech of love and mutual recognition—the recognition, the knowledge of self and Other, available only to an “I” speaking to a “Thou,” subject to subject. In a transformative vision it reveals the person as a subject, not merely an object to be manipulated, but a person made for sacrifice and for others.

And this is what the men and women who have sacrificed in the age of COVID-19 have revealed to us: that man is indeed made in the image of God, capable of the sacrifices that prove it and the knowledge and recognition that are its fruit.

May we be worthy of their example.