On a number of occasions, I taught American Government in the state prison. I would enter via the front gate, go through security, then make my way across the prison yard, between the cell blocks, to the flat-roofed brick building wherein resided the classrooms. Since prisons pay little attention to beauty, the utilitarian spaces were ungilded.

Classical education should do more than enhance the reasoning powers. It should also cultivate the imagination, that “small instance of a God-like power in man.”

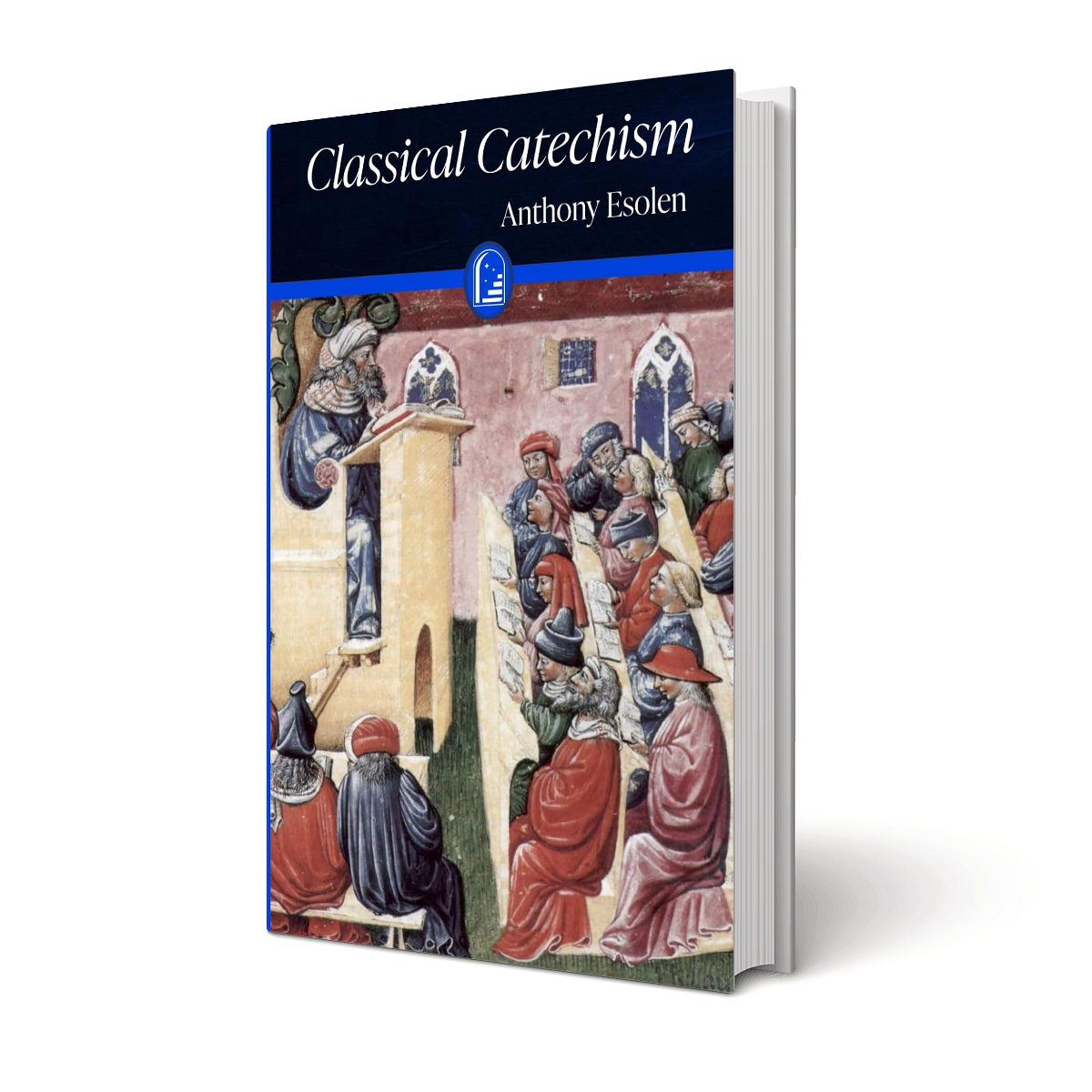

By Anthony Esolen

(Independently Published, 2024)

One day, on my way home, I drove by one of our large public high schools and was immediately struck by its architectural similarity to the cell blocks and common spaces of the prison. Put some barbed wire around the school and it would be hard to tell it apart from the prison. I recalled my time in high school and college classrooms, even as recently as my time teaching there, and noticed again little difference in the organization of space. No wonder, I mused, I frequently experienced my school years as a form of incarceration. Very little sparked the imagination or engaged the mind.

The mind and heart and hands of a child, of a student, yearn to be free, unfettered by stale routine or confusing ends. Any system may in part be evaluated by its results. Increasingly we see education as a consumer good or, worse, as a large productive apparatus whose “product” is the graduate, typically understood as either an active consumer and producer in our mass economy or a “citizen” in a mass democracy, or the nonsensical “global citizen.” If we evaluate our educational systems honestly, however, we will marvel at how naturally curious and frequently amazed toddlers get turned into jaded and cynical adults.

Man is bios qaumatos—the being that wonders, that which prompts humans to search for wisdom, to seek the depths and breadths of the reality in which they participate. Sullenness, isolation, rebellion, and anger are not intrinsic features of being a teenager; they are acquired traits that result from the systematic suppression of wonder, the isolation from the fullness of reality. No doubt this is what Nietzsche realized when he opined that a man’s maturity consists in recovering the seriousness he had as a child at play.

I recently talked with some friends who proudly boasted that their 13-year-old grandson was reading Shakespeare, his curiosity sparked by an English lesson. Why shouldn’t 13-year-olds read Shakespeare? What better time to start? In our system of mass education, we expect both too much and too little from our children, but only because we have decoupled education from that sense of wonder, and such decoupling necessarily results in a disintegration of the educational enterprise and ultimately of the selves who labor in and under it.

In the blacktopped world of education, shoots of life still spring up, none more promisingly and hopefully than in the classical school movement. Unlike much of our public education, the classical school movement treats young people as whole creatures who do not need to be made to wonder or to be curious about the world around them; they only need that instinct properly guided and nurtured. As any parent can attest, young children are inveterate and often exhausting question askers, the mode in which the mind most directly expresses both its engagement in the world and its freedom. Why would we seek to stifle that impulse?

Classical schools arose in part when parents began to despair concerning the direction of the public schools and the concomitant development of their children. Surely there had to be a better, more humane way to teach children. Wittingly or not, the movement predicated itself on Aristotle’s teaching concerning causality: the material, formal, efficient, and final causes that make a thing a fully formed version of its latent potential. In education, we might think of the child as the material cause, that upon which (whom) action is taken and from which the student is made. The formal cause—that which tells us what kind of thing a thing is—views the student as a being whose sense of wonder helps it become a creature who knows things. An educated person is, after all, a person who seeks to know all things worth knowing. Nothing human is alien to them. The efficient cause of the educated person is the curriculum as served by the teacher. Too often our colleges see the curriculum as serving the instructor rather than the instructor serving the curriculum, at which point it no longer is a path to be followed but only a series of waystations on the road to nowhere. A good curriculum keeps the final cause in mind, and the final purpose of a good education should never be subordinate to some other end, such as economic or political activity. The full flourishing of the person is the goal.

All well and good, but how to give these instincts and ideas institutional form so that students experience school as liberating rather than subjugating? For parents and entrepreneurs and churches that seek to create a good classical school, Anthony Esolen provides a brief but excellent overview in his Classical Catechism. Why “catechism”? Esolen uses the question-and-answer form to guide readers to a sound understanding of what both a classical education and a classical school look like. I love my children, but I can’t help but believe they would be more fully formed as persons had they attended the kind of school Esolen outlines.

Esolen may reveal his own prejudices in his guide—placing books, literature, and poetry at the center of the enterprise—but his biases aren’t necessarily wrong, especially since they address the question posed so many years ago by the Psalmist: “What is man that You are mindful of him, the son of man that You visit him?” No education worth its salt can or should avoid helping young people get traction on the key questions of any life worth living: Who am I? Where did I come from? Whither am I going? What is expected of me in the span allotted me?

Education should start with the sense of wonder, of miracle, that results from reflecting on one’s own existence.

Too often our educational systems, operating in a fragmentary and often reductionistic fashion, compress the student’s experience in such a way as to place that student in a figurative little-ease, whereupon freedom would consist in a joyous stretching outside its bounds. At its worse, it decapitates, placing beyond any consideration the very questions that matter most to us. It becomes technical rather than humane. “The human being,” Esolen reminds us, “is not a computing device, not a gear in a machine, not a bundle of political ambitions, not a bed of erotic desires. He is capax universi: his mind is open to knowing the truth of anything that exists, both singly and in its relation to other things. He is a world open to the world.”

This openness to the world closes upon itself when wonder attenuates. Education should start with the sense of wonder, of miracle, that results from reflecting on one’s own existence. Esolen tells us that good instruction always starts with what is nearest at hand and most familiar and then moves outward. St. Augustine’s rumination that “men go abroad to wonder at the heights of mountains, at the huge waves of the sea, at the long courses of the rivers, at the vast compass of the ocean, at the circular motions of the stars, and they pass by themselves without wondering” reminds us of the source and goal of a good education, and also stands as a condemnation of so much contemporary education that does little more than turn people into voyeurs, jaded idlers in a barren garden.

Esolen offers a fecund education, revealed in part on his insistence, undoubtedly controversial to some, that a good education take seriously the differences between the sexes and provide an environment wherein their awakening to one another can find its proper form. Indeed, Esolen’s whole approach might be thought of as a proper relating of matter and form. Thus he remonstrates that those creating a school must pay attention not only to the curriculum but also to the buildings where education takes place, warning against mere utilitarian design, stressing proper scale while ensuring that the exterior of the building “should be a place where beauty meets the eye even from a distance.” A school’s design will give meaning to the sense of “hallowed halls” and engagement with a rich and worthy past.

This, too, relates to Esolen’s holistic approach. Certainly a classical education, one that has the humanities at the center but also teaches math and science, develops our capacities of reason but does not neglect the imagination that is “reason come to life.” Every act of the imagination, Esolen insists, “is a small instance of a God-like power in man” that enables us “to summon up a world” that is a deeper movement into reality.

The exterior of the school building "should be a place where beauty meets the eye even from a distance."

Esolen stresses that education involves a proper ordering of things, and this ordering relates to the relationship between teachers and students (authority), students to one another (seniority), students to work (bringing a project to completion), and modes of work to one another (what Esolen calls the “order of excellence” and relates to our ability to develop taste and engage in discriminating judgments). Finally, education should order the student to his or her ultimate purpose, from which alone meaning is generated.

All this is on the affirmative side, but a well-wrought education also attends to what needs to be excluded. St. Thomas wisely observed that distraction is in many ways the most noxious kind of acedia, for it creates a busyness without actual accomplishment. It deceives us. In an age when we are, in Eliot’s memorable phrase, distracted from distraction by distraction, the need for focus and attentiveness is more imperative than ever. A good school would eliminate all distractions, especially technological ones. It also encourages a deep seeing, an attentiveness to the world outside the mind and outside the classroom. Classical schools thus encourage students to get their hands dirty, to sensitively examine things in their wholeness, “for the hands to have callouses and for fingers to be smudged with the stuff of things.”

A classical education ennobles, it lifts up, and therefore avoids that which degrades or tears down. Rather than “critical thinking,” it emphasizes piety; it avoids cynicism with regard to the past and the regnant generous bigotry with regard to present prejudices. It introduces students “to the lost features of their humanity” that results from growing up in a world with no shared culture. Above all, it avoids political indoctrination, “for enmity is not a good soil for learning.”

Education at its best is an act of remembering, although Esolen prefers the term “recollecting” because it implies an intentional, rational gathering and ordering of material. It should reestablish our membership both in the overall order of things and alongside others, but also grow again those parts of ourselves we have lost, like an amputee being made whole again. Able to stretch once more, the student will enjoy school as a haven rather than a cell.