For many years, Christianity was a soft target for critics of Western culture who interpreted its sexual codes as oppressive, its missionaries as agents of imperialism who destroyed indigenous cultures, and its institutions as corrupt. There was certainly evidence to support such claims and, in a West subject to an insatiable cultural Oedipus complex, the ritual slaying of the Christian God became a staple of the secular culture industry. That secularism had nothing of equivalent potency with which to replace him has in recent years come to the attention of a small but (currently) growing group of intellectuals and culture makers.

If you have any doubts about the salutary effects of the Christian Faith on English life, culture, and manners, a new book will shore up your faith.

By Bijan Omrani

(Forum, 2025)

Perhaps the most significant book to emerge from this cultural moment is Tom Holland’s Dominion, which points not only to the religious origins of Western culture in general but even to those very things that became the tools of secularism, such as universal human rights and the various schools of feminism. Now, Bijan Omrani has entered the lists on the side of Christianity, at least as a positive cultural force. His latest book, God Is an Englishman: Christianity and the Creation of England, in many ways a demonstration of the validity of Holland’s basic argument narrowly applied to England and the English, is an engaging read. It is both a concise account of key aspects of English history and culture and a heartfelt plea for the Christianity that the author himself holds dear.

That Christianity, particularly that of the Anglican church, had a formative effect on English culture is indisputable. What is contentious today is whether that influence was positive, benign, or malign. Decades of self-loathing, fueled by academia, pundits such as Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins, and outfits such as the BBC, have rendered any claim to its being positive or benign countercultural and controversial. In that context, Omrani’s careful marshaling of evidence and thoughtful narrative represents a measured and balanced response to the critics. Touching on a variety of topics, such as religion itself, legal theory, music, communal life, education, politics, and literature, Omrani shows how Christianity’s influence was pervasive and often in good ways.

Three elements of the book stand out. The first is how Christianity shaped English identity. Non-British readers need to understand, of course, that “British” is really a political construct. No Welshman, Scotsman, or Ulsterman would accept the term as an adequate description of their identity, and the English do so only when convenient (as when a Scotsman wins at Wimbledon). Omrani does a fine job showing how Christianity became a cultural force in the first millennium and was key to the various moves toward the emergence of the monarchy. It also shaped the experience of time, not only through the convention of numbering years from the birth of Christ but also through the rhythm of the liturgical calendar. One might even extend Omrani’s analysis here and say that the move from the liturgical calendar to weekly Sabbatarianism under the Puritans paved the way for the disciplined workweek that a production-based, rather than an agrarian, economy requires, thus paving the way for later English industrial success.

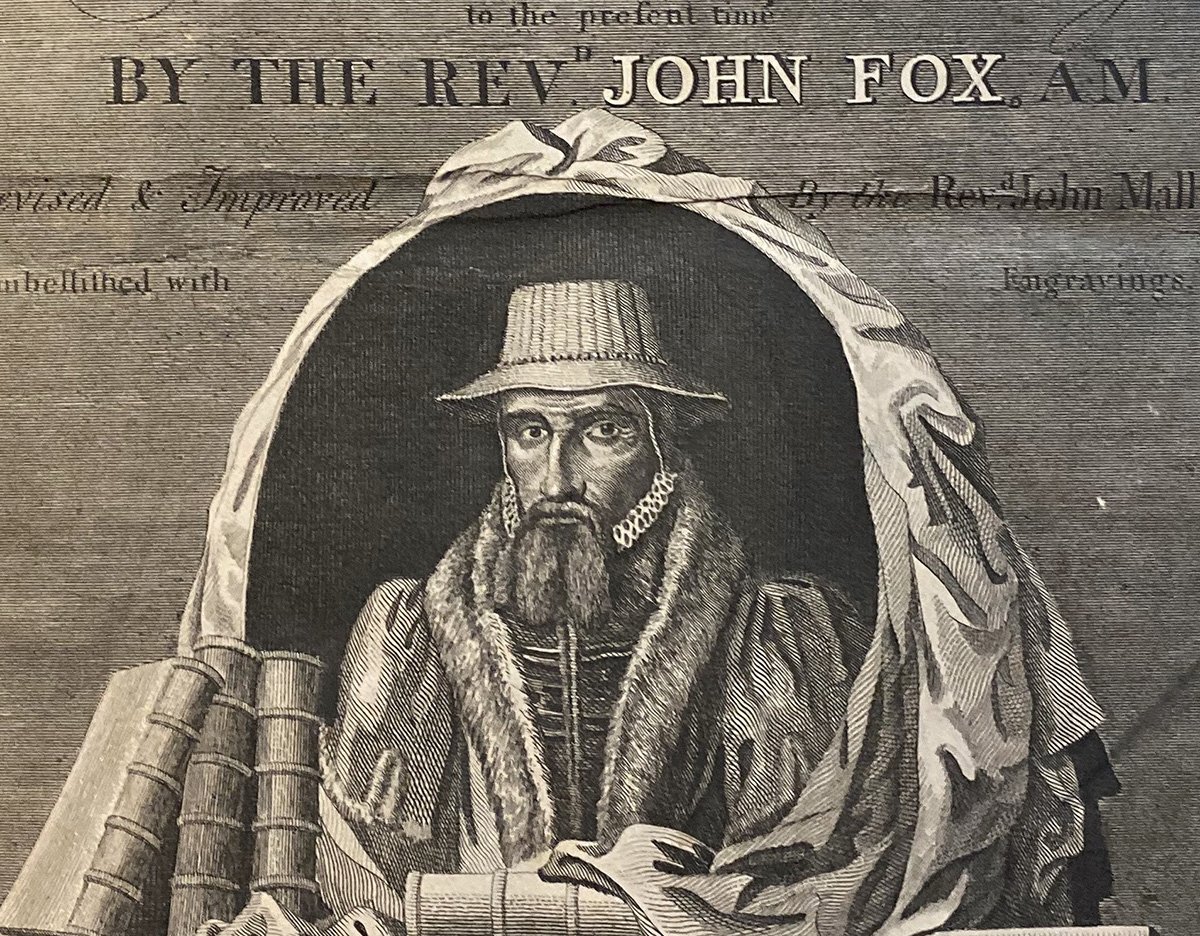

Omrani skates somewhat lightly over the relative independence of the English church from Rome (an advantage of being an island) and does not spend any time examining the importance of the distinctively Protestant nature of the English monarchy after the Reformation. He does highlight the fear of Catholic plots in the early modern period and Guy Fawkes Day as an important addition to the calendar, along with sporadic anti-Catholic violence. Perhaps oddly, he fails to mention John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, popularly known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. This volume did more than any other to shape the anti-Catholic nature of England’s church life and Christian imagination. Indeed, at one time it was a legal requirement that a copy be held by all cathedral chapter clergy. That granted it a status shared only by the Book of Common Prayer and the Bible itself. It helped to define English Christianity as particularly anti-Catholic.

The King James version of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer came to shape the modern English language.

The second dimension of Omrani’s argument is that of the salubrious influence of Christianity on English culture. For example, it was widely understood until recent times that English common law took its guiding commonsense principles from Christianity. Christianity also inspired great poetry, from Herbert and Donne to Eliot. Through the King James Version of the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, it also came to shape the modern English language, particularly in its finest literary forms. Church music was also central to parish life and came to pervade education as well. It was not simply church services but also school assemblies that were marked by the singing of hymns, a practice that has all but vanished from the modern English experience. Omrani was at school in the ’90s, I was there in the late ’70s and ’80s, but our experiences were very similar. Corporate singing at assembly had a lasting effect. Even today, I have a lump in my throat whenever I hear “Jerusalem,” the words of which I can recall with ease—scarcely an orthodox hymn but full of deep, nostalgic resonances that provoke in me a longing for those lost halcyon days of youth.

And then there was the well-known connection between English Christianity and humane social reforms. William Wilberforce and Hannah More are well known, others less so but still very influential. Indeed, Omrani does a particularly good job of describing the life and contributions of Dr. Thomas John Barnardo, an Irish philanthropist who founded homes for impoverished children. He also includes the hapless Charles Kingsley, remembered today as the incompetent critic whom Newman demolished in his Apologia pro Vita Sua. In his own day, Kingsley played an important role in raising public awareness of the brutal phenomenon of child chimney sweeps, particularly through his novel The Water Babies. In each case, Christianity was central, not incidental, to the motives for reform. It is easy to see why: The Christian teaching that each and every human being is made in God’s image provided a framework for treating others as human beings and for doing so as one would wish to be treated. None of this is news to any who know English cultural history, but it is very useful to have it set forth in such a clear and thoughtful manner. The list of reforms wrought by Christianity is particularly impressive and should be pondered by any still intimidated by the tendentious histories underlying the claims that Christianity has only ever been harmful to humanity.

Particularly entertaining is the section where Omrani speaks of the notorious eccentricity of many English clerics, something that fed into a taste for national nonconformity. My favorite in this regard is the Rev. John Froude, who would burn down the hayricks of parishioners who were delinquent on their tithes and dig holes in the road to prevent visits from his bishop, and who got his deacon drunk and hanged him upside down to prevent him leading evensong. Those, as one might say, were the days when society produced real characters and not merely the performative transgressors of our social media age.

Not all of Omrani’s narrative is relevant to his central argument. The chapter on Richard Rolle, Julian of Norwich, and others typically bracketed together using the later term “mysticism” is interesting enough but does not add to the overall thesis beyond addressing the rather nebulous criticism that English Christianity lacked “spirituality.” Some of the theological references are also misleading. For example, the focus on John Calvin as the source of a virtuous work ethic and his connection to Protestant notions of justification is somewhat overstated, as these things were more generically Protestant, perhaps Reformed, than simply the fruit of one Reformer from Geneva. Also the reference to John Calvin’s commitment to the principle that the finite cannot contain the infinite (often referred to as the extra Calvinisticum) as that which prevented him from seeing how the supernatural could manifest itself in and through the natural is wrong. The principle is a key part of standard Christology, well-established by Calvin’s day, and intended to guard the integrity of Christ’s human nature, not drive a hard wedge between the natural and the supernatural. Indeed, it is arguable that this principle offered an account of the opposite: how the infinite could be manifest in the finite without either losing its integrity. Yes, Calvin did not think that shrines and particular places had an inherent holiness, but that was based on his understanding of true worship and of the activity of the Holy Spirit, not the extra Calvinisticum.

The third part of Omrani’s argument is found in Part Two, where he makes his case for what a revival of interest in Christianity could offer to England. He critiques the old secularization thesis as too simplistic and sets the decline of Christianity’s cultural influence against the background of both technological developments and shifts in anthropology, the former of which rendered Christian values unnecessary (e.g., Why can’t sex be recreational and uncommitted once we have contraceptives and antibiotics to obviate unfortunate consequences of promiscuity?), the latter of which made them oppressive (e.g., If sex is the way to human satisfaction, rules that restrict desire take on a negative, even sinister, appearance). The results, however, have not been good. The nation has lost its shared moral imagination. Solitude has replaced community. Christianity, in offering a moral framework and a community, can answer both these questions. More than that, Omrani, a Christian himself, makes the case in the final chapter for Christianity as answering the human need for the sacred.

This is where I find myself dissenting somewhat. Certainly human beings have a longing for the sacred. And it is clear that an approach to reality that is purely immanent is the source of many of the problems we now face as Western societies lose both their cultural confidence and their consequent ability to grip the imaginations of the populace. Omrani’s closing paragraphs are deeply moving, as he quotes from, and then builds upon, the Meditations of Thomas Traherne, who points to the glorious transcendent context of this world. But Christianity is not just a religion of transcendence. It is also a religion of grace, grace made necessary by human rebellion against the creator. And the Incarnation is not just an awe-inspiring mystery. It is also a response to sin and death, the only thing that makes the presence of the transcendent, holy God bearable. And it demands a moral, not merely aesthetic, response from us—that of repentance and faith. In short, Christianity is true not simply because it answers man’s need for the sacred and offers him a moral universe and a community to which he may belong. It also answers his need—whether or not he is aware of that need—for forgiveness. That is a note we cannot mute in the current discussions of religion and culture without losing something central to the Christian faith.

Nonetheless, this is a delightful book, packed with learning but written with a light, engaging touch. It is a most helpful expression of the current intellectual revival of interest in Christianity.