Harris Bor’s Staying Human: A Jewish Theology for the Age of Artificial Intelligence is an ambitious book. Its message can be put simply: Jewish religious tradition has the resources to respond to a world in which technology controls human beings. Bor is responding to the promise and threat of a future in which artificial intelligence renders human choice and individuality obsolete, a future Bor refers to as “the singularity,” following techno-futurist Ray Kurzweil. Bor is convinced that the singularity is a “quasi-religious” notion that raises “essentially theological” questions about the nature of the universe and human life. Indeed, Bor approaches the Jewish religious tradition in light of the philosophical concepts of Spinoza and Heidegger because he believes that “the philosophical roots of the idea of the singularity as God” need to be uncovered.

Can Jewish theology save us from the slavery of artificial intelligence by holding in tension science and faith, imagination and technology, unity and difference?

By Harris Bor

(Cascade Books, 2021)

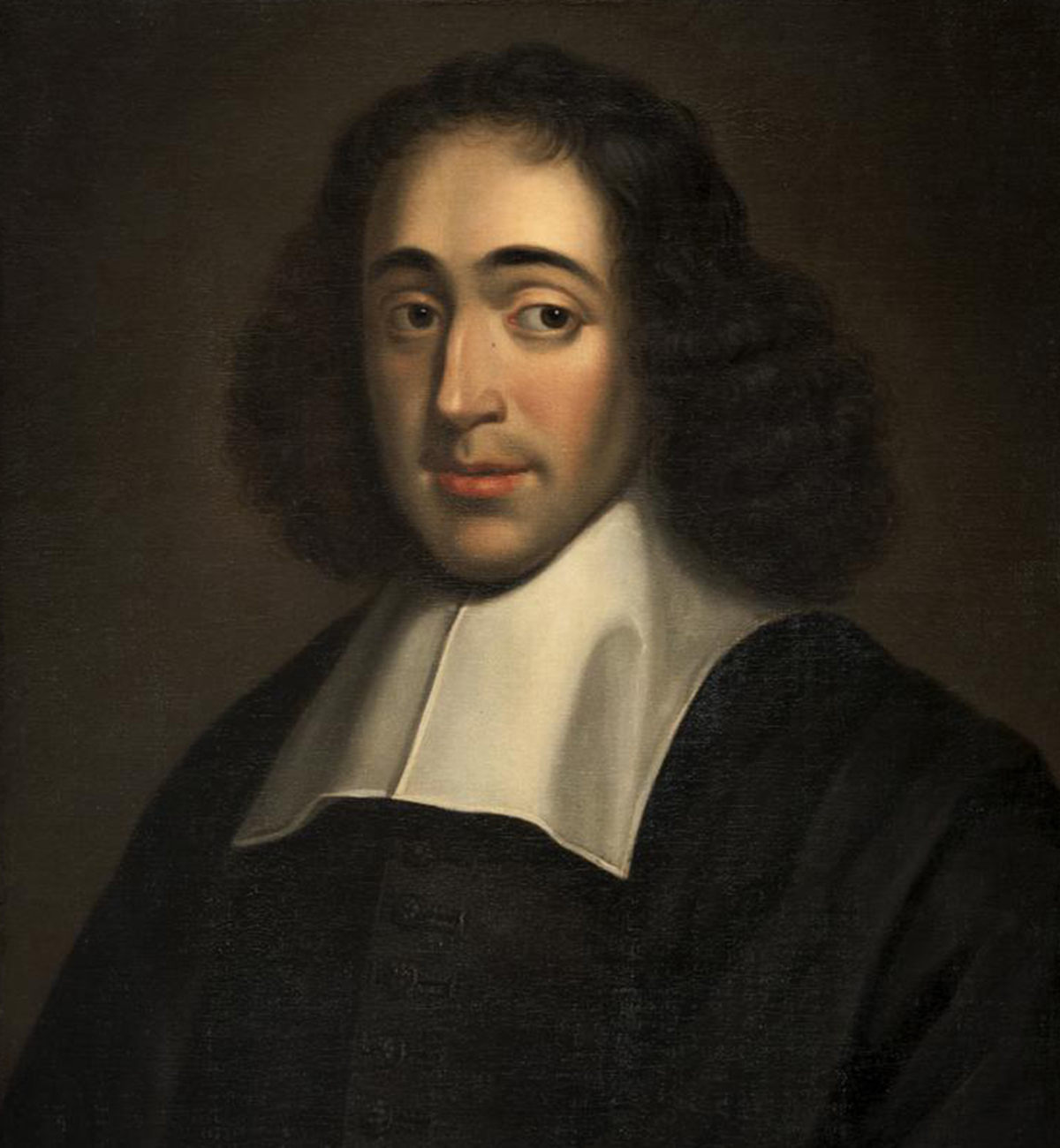

Bor is guided by the conviction that, appearances to the contrary, Spinoza and Heidegger think in a way that aligns deeply with the Jewish approach to life and that they shed light on elements of this approach that counter the pull of technology. In Bor’s view, Spinoza—the heretic who denied Mosaic authorship of the Torah—develops in his Ethics the Jewish idea of God as totality or oneness, while Heidegger—who never expressed remorse for joining the Nazi party—elaborates a Jewish conception of being in which God as creator, God as wholly different and wholly other, can reveal himself. Bor’s argument is that Jewish life continuously moves from the Spinozist God of oneness and totality to the Heideggerian God of difference and otherness and back again, and therefore that Jewish life reconciles these opposed conceptions of God.

But Staying Human forces us to ask what bearing the theological conception of God as oneness has on the techno-futurist idea of the singularity. Does the possibility of a world governed by artificial intelligence rest on an ontological claim about the unity and omnipresence of God? Bor answers in the affirmative. The singularity expresses, in his view, “humanity’s hypothetical collective wish” to achieve complete wisdom and immortality, to overcome individuation and subjectivity, to participate in the eternal. Bor assures us that recognition of the singularity need not result in the obliteration of human individuality. He thinks he has developed “a rational mysticism that seeks to resist the idea of the singularity while embracing its theological implications: a religion of the everyday capable of balancing all aspects of being while holding tight to a God who is both singular and wholly other.” It is no surprise that Bor is attracted to a religion that combines reason and mysticism if we keep in mind that his ultimate ambition is “to lay the groundwork for a synthesis of immanence and transcendence.” A theology based on such a synthesis “demands living with these conflicting approaches and ideas without fully embracing either.”

As we can see, Bor is determined to show that two opposed positions can be maintained consistently without sacrificing either. Indeed, Bor thinks he is charting a moderate course between the extremes of immanence and transcendence, unity and difference, universality and particularity. He champions what he calls “a wholesome religious path” that “requires a consciousness of, and orientation toward, oneness,” but that also requires the realization that the “sense of the singularity is only the starting point. The next step is to embrace individuation and variety, to engage the concrete universe in all its difference, beauty, and chaos.”

To whom does Bor think this message will appeal? Not only to Orthodox Jews, who, like Bor, are “heavily influenced by rationalist and postmodern thought,” but to “seekers of all denominations and outlooks” who want “a path or view of the world sympathetic to tradition but founded on a universal wisdom,” who share “an awareness, peculiarly postmodern, that the traditions we are born into are flawed, imperfect, and one of myriad alternatives.” Bor claims to be working for the general “renewal of religious practice and thinking” and for “increasing mutual understanding across religions.”

Unfortunately, Bor does not come close to meeting the extraordinary tasks he sets himself. He never tires of asserting he has found a happy middle ground between opposed positions, but he is unable to demonstrate why the balancing act he finds convincing does more than juxtapose irreconcilable alternatives. He speaks of the necessity of “walking the tightrope between reason and mysticism, science and imagination, the universal and the particular,” but it is hard to escape the impression that Bor merely jumps between the two extremes, sometimes prioritizing one position to the detriment of the other and vice versa. Bor’s treatment of two key ideas in particular makes the shoddiness of his reasoning uncomfortably apparent. These ideas are death and revelation. Since one’s approach to death tends to determine one’s attitude toward revelation, I will begin my discussion with death.

Bor thinks that accepting the inevitability of death is key to living an ethical life: “An awareness of death is an inspiration for correct living and a stimulus to ensure the transmission of values down to the next generation.” However, he has to admit that, from the scientific, technological perspective of singularity, “death is not a part of the natural cycle, but a problem to be overcome.” The scientific, technological orientation aims not merely to prolong life but to conquer death. But the desire to achieve immortality, as Bor emphasizes in his discussion of the biblical account of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, goes with a spiritual slavery incompatible with human freedom and morality: “Slavery, like the idea of the technological singularity, treats humans as cogs in a machine, without will or worth save as a means to some external material end.” The participant in the singularity, like the slave, “is unaware of his servitude. He is passive in his suffering and sees no alternative world beyond the system.” Unless Bor is suggesting a compromise between slavery and freedom, it is hard to understand how he thinks the notion of singularity can be reconciled with religious morality.

Does the possibility of a world governed by artificial intelligence rest on an ontological claim about the unity and omnipresence of God? Bor answers in the affirmative.

Bor thinks that accepting the inevitability of death is key to living an ethical life: “An awareness of death is an inspiration for correct living and a stimulus to ensure the transmission of values down to the next generation.” However, he has to admit that, from the scientific, technological perspective of singularity, “death is not a part of the natural cycle, but a problem to be overcome.” The scientific, technological orientation aims not merely to prolong life but to conquer death. But the desire to achieve immortality, as Bor emphasizes in his discussion of the biblical account of the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, goes with a spiritual slavery incompatible with human freedom and morality: “Slavery, like the idea of the technological singularity, treats humans as cogs in a machine, without will or worth save as a means to some external material end.” The participant in the singularity, like the slave, “is unaware of his servitude. He is passive in his suffering and sees no alternative world beyond the system.” Unless Bor is suggesting a compromise between slavery and freedom, it is hard to understand how he thinks the notion of singularity can be reconciled with religious morality.

Bor’s analysis of Spinoza, whom he does not hesitate to call the “philosopher of singularity,” makes no mention of the famous 67th proposition of Ethics Book 4, which states that “a free man thinks of death least of all things; and his wisdom is a meditation not of death but of life.” Spinoza’s conception of human freedom could not be more opposed to Heidegger’s conception, championed by Bor, of being-towards-death as the proper orientation of the human being. For Heidegger, according to Bor, only death can be “that which is uniquely mine” since an awareness of it produces the existential anxiety through which “a space is created to view that which we care most about.” What Bor cares most about is developing a relationship with “the other,” understood not only as another human being but more fundamentally as God. But it is not clear that scientific reason as Spinoza conceives it leaves room for such a relationship. As Bor emphasizes, Spinoza’s conception of scientific reason points to a way of life based on personal autonomy and independence from external causes. Connection with others is, for Spinoza, not a sacred commandment but a matter of expedience.

With this in mind, we are entitled to ask whether Spinoza’s God of oneness can be known through revelation and, if not, whether it should be incorporated into Jewish life. Bor defines revelation as “the light that shines through the tear caused by God’s withdrawal, made possible by the break in the totality of oneness.” However, Spinoza denies that God can withdraw from the world or create a break in the totality of oneness. Indeed, according to Jewish tradition, God withdraws through the miracle of creation, but Spinoza claims that miracles are incompatible with God’s nature, a fact that Bor nowhere mentions. He does refer once to “imagination as the power of revelation.” In saying this, Bor surely does not mean that revelation is a human invention, but that ultimately imagination should take precedence over science. According to Bor, Heidegger corrects Spinoza because he shows that “imagination is not the enemy of reason, but the phenomenon which gives rise to scientific thinking in the first place.” But if imagination is the basis for science, how should we take Bor’s claim “to believe in the primacy of reason … to see the advantage of adopting it as the core of the spiritual path”?

Bor never tells us what he means by spirituality, but it surely has something to do with revelation. Yet the more Bor seeks to fuse spirituality with reason, the more the necessity for revelation recedes. Bor says that “science is not just a description of the external world but how we come to access ultimate meaning.” Yet Bor also tells us that religion, not science, governs “the realm of value and meaning.” If reason or science can provide us with ultimate meaning, why should we heed “the experience of being called” that Bor associates with revelation?

Staying Human may be a well-intentioned attempt to show that science and religion can be harmonized, but when we consider the implications of Bor’s efforts, we are left suspecting that they should be kept separate. Bor claims to be a defender of enlightened orthodoxy, but by blurring the boundaries between science and religion, and between reason and faith, he compromises both. When faced with the concrete question of the permissibility of using technology on the Sabbath, for example, Bor leaves us with the following tepid statement: “I think that, apart from limited exceptions, Shabbat should remain technology-free for as long as possible.” In accepting that a technology-free Sabbath may not be possible in the future, Bor tacitly admits that technology has the power to render the divine commandments obsolete. This claim would be less disturbing if Bor made no pretensions to defending revelation. But one expects more from someone as deeply committed to an Orthodox Jewish way of life as Bor is.