Criticizing modern ideologues in his book The Politics of Prudence, Russell Kirk (1918–1994) noted that it was “the practical statesman, rather than the visionary recluse, who has maintained a healthy tension between the claims of authority and the claims of freedom; who has shaped a tolerable political constitution.” We note that, except for Great Britain, no other country had more conservative statesmen than Brazil during the period of parliamentary monarchy: 1822–89. During the reign of Dom Pedro II (1825–1891), the combination of the wise actions of the monarch, the solid institutional foundations offered by the Constitution of 1824, and the prudent actions of the statesmen who governed the country made for a period of greatest political stability. The challenge faced by Brazilian conservatives, however, was the dual responsibility of safeguarding the traditional monarchical institution of Portuguese origin without adopting patrimonialism, absolutism, and mercantilism, and fostering freedom without descending into the egalitarian and almost anarchic excesses of democratism, as proposed by Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) and adopted in both the French Revolution and the independence movements of Hispanic America.

Lisboa’s intellectual contributions and work in the political arena as a statesman can be compared to the conservative trajectory of John Adams.

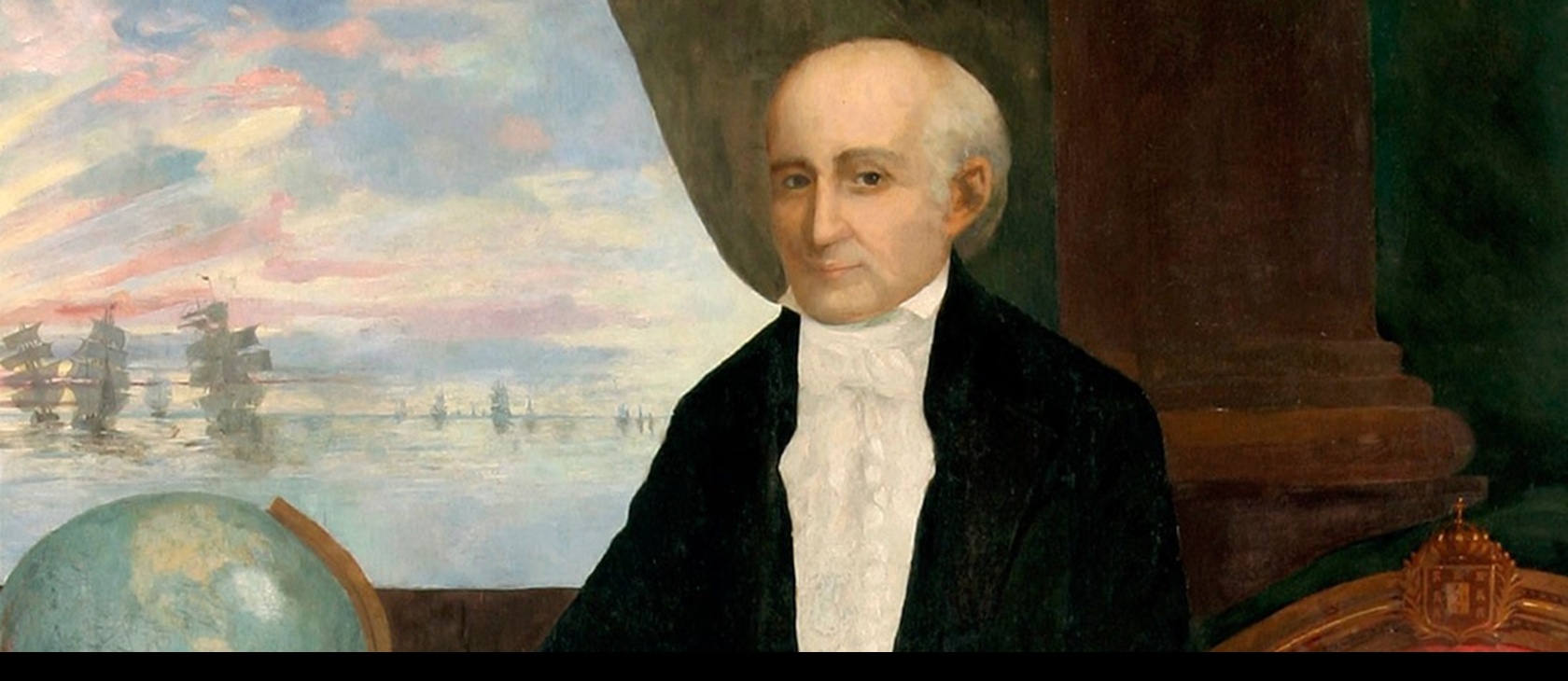

Even before the creation of the Conservative Party in 1837, the spread of conservatism in Brazil was undertaken by the jurist, economist, historian, publicist, statesman and Catholic moral philosopher José da Silva Lisboa (1756–1835), Viscount of Cairu, who, in addition to having defended some principles of late Iberian scholasticism, in the line of the Jesuits Francisco Suárez (1548–1617) and António Vieira (1608–1697), also disseminated in Portuguese the counterrevolutionary thought of Edmund Burke (1729–1797), the moral and economic theses of Adam Smith (1723–1790), and the writings of several other authors aligned with the defense of the rule of law and the free market economy. In 1812, the first edition of Extracts from the Political and Economic Works of the Great Edmund Burke was published, translated into Portuguese and with a preface by Lisboa, with the aim that the texts should serve as “an antidote against the pestilent miasma and subtle poison of the seeds of anarchy and tyranny in France, which, insensibly, fly through good and bad airs and through all the winds of the Globe.”

In several other works, notably Principles of Political Economy (1804), Studies of the Common Good and Political Economy (1819), and Manual of Orthodox Politics (1832), Lisboa defended the importance of ordered freedom for the political, economic, and social development of Brazil.

José da Silva Lisboa was born on July 16, 1756, in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil, the son of an architect, Henrique da Silva Lisboa, and Helena Nunes de Jesus. He began his studies of philosophy, grammar, Latin, music theory, and piano at the Carmelite convent in Salvador at the age of eight. In 1773, he traveled to Lisbon, Portugal, where he continued his training in rhetoric and oratory. In 1774, he entered the University of Coimbra, graduating with degrees in canon law and philosophy, in addition to having studied Greek and Hebrew. (He would go on to teach these two languages at the Royal College of Arts of Coimbra.)

After returning to Brazil in 1780, he held the chairs of both moral philosophy and Greek language—in addition to becoming a pioneer in the teaching of political economy in his country. In 1784, he married Ana Francisca Benedita de Figueiredo (†1811), with whom he had 14 children. In 1797, he was appointed deputy and eventually secretary of the Board of Inspectorate of Agriculture and Commerce of Bahia, having combined his practical experience with solid theoretical training in such titles as Principle of Mercantile Law and Laws of the Navy (1801) and Observations on the Frankness of Industry, and Establishment of Factories in Brazil (1810). In these works he proposed the free market as a necessary means for the development of the country, in addition to defending the end of slavery, emphasizing that the use of this inhumane labor force was an inefficient means for generating wealth.

The main objective of Lisboa’s work was to contribute to the pedagogical formation of the conscience of the Brazilian elites.

Upon the invasion of Portugal by the troops of Napoleon Bonaparte, the seat of the Portuguese monarchy was transferred to Brazil in 1808, with the arrival of queen Dona Maria I (1734–1816), the future Portuguese king Dom João VI (1767–1826), the future Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro I (1798–1834), and the other members of the royal family, accompanied by the court. Upon disembarking in Salvador, the then-Prince Regent Dom João received from Lisboa an explanation of the advantages of opening Brazilian ports to friendly nations, which, in part, resulted in the Royal Charter of January 24, 1808, which guaranteed the establishment of free trade in Brazil.

Faced with the Porto Revolution in 1820, which forced Dom João to return to Europe in 1821 and led to the independence of Brazil in 1822, Lisboa defended in some texts the maintenance of a United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves. However, faced with the intransigence of the revolutionaries, he decided to support Dom Pedro in the measures that led to the separation of the two nations.

Throughout the last decade of his life, Lisboa participated in the constituent assembly in 1823, was an adviser to Emperor Dom Pedro I, and held various public offices. He was also appointed to the Senate of the Empire, a seat he held until his death on August 20, 1835, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, at the age of 79. The main objective of his life’s work was to effectively contribute to the pedagogical formation of the conscience of the Brazilian elites, not only in resolving the legal, economic, political, and social problems of the nascent independent nation, but also in addressing issues related to a greater understanding of the historical-cultural identity of Brazil, the ethical foundations necessary for life in society, and the orthodox religious principles that should still be instilled in a heterodox Christian environment.

Even though Lisboa was a defender of the representative system and freedom of expression, he nevertheless possessed a lucid understanding of the moral and intellectual failings of the Brazilian elites, a factor reflected in the institutional fragility of parliament, which is why, unlike his liberal contemporaries, he emphasized the need to strengthen the authority of the monarch. In addition, Lisboa never refrained from emphasizing that the existence of democratic institutions would only be possible through the increase of economic freedom and the internalization of certain moral principles, by both the majority of citizens and, mainly, by political leaders.

In many aspects, Lisboa’s intellectual contributions and work in the political arena as a statesman can be compared to the conservative trajectory of John Adams (1735–1826), particularly in recognizing the importance of the moral, economic, and political role of the so-called “natural aristocracy.” All told, Lisboa’s vast bibliography and his robust public life provided much-needed guidance for subsequent generations of Brazilian conservatives.