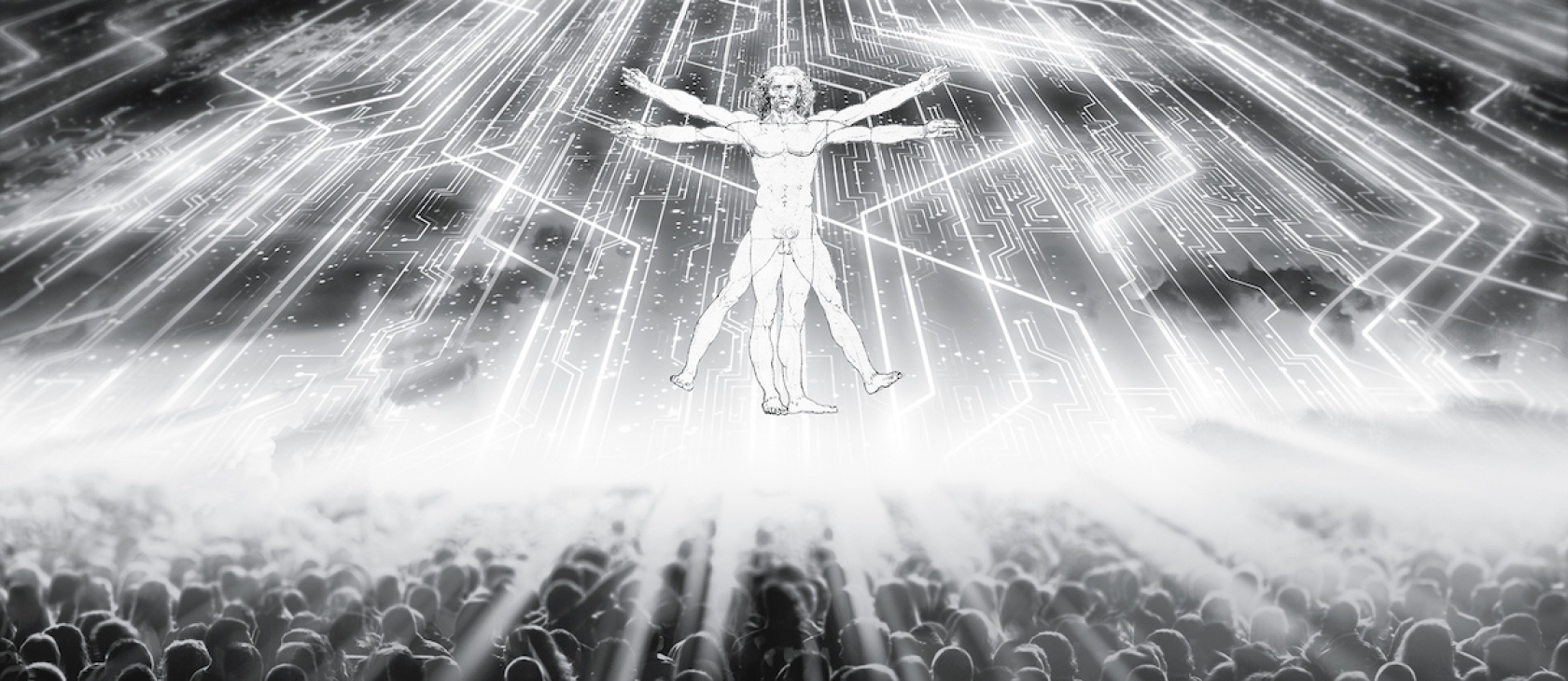

Transhumanism is a vision of the future of humanity in which applied technologies are supposed to enhance and upgrade human existence. According to the transhumanist story, evolution has brought us very far indeed—to the moon and back, so far. Yet as an intelligent species, humanity is still very primitive and thus stands in need of upgrading. Given the rise of new technologies, transhumanists argue that we can—nay, should!—overcome our current evolutionary limitations in terms of physiology, emotion, cognition, and (at least sometimes) morality. The Transhumanist Declaration, the work of a variety of international authors and “modified” repeatedly since its publication in 1998, states that

Humanity stands to be profoundly affected by science and technology in the future. We envision the possibility of broadening human potential by overcoming aging, cognitive shortcomings, involuntary suffering, and our confinement to planet Earth.

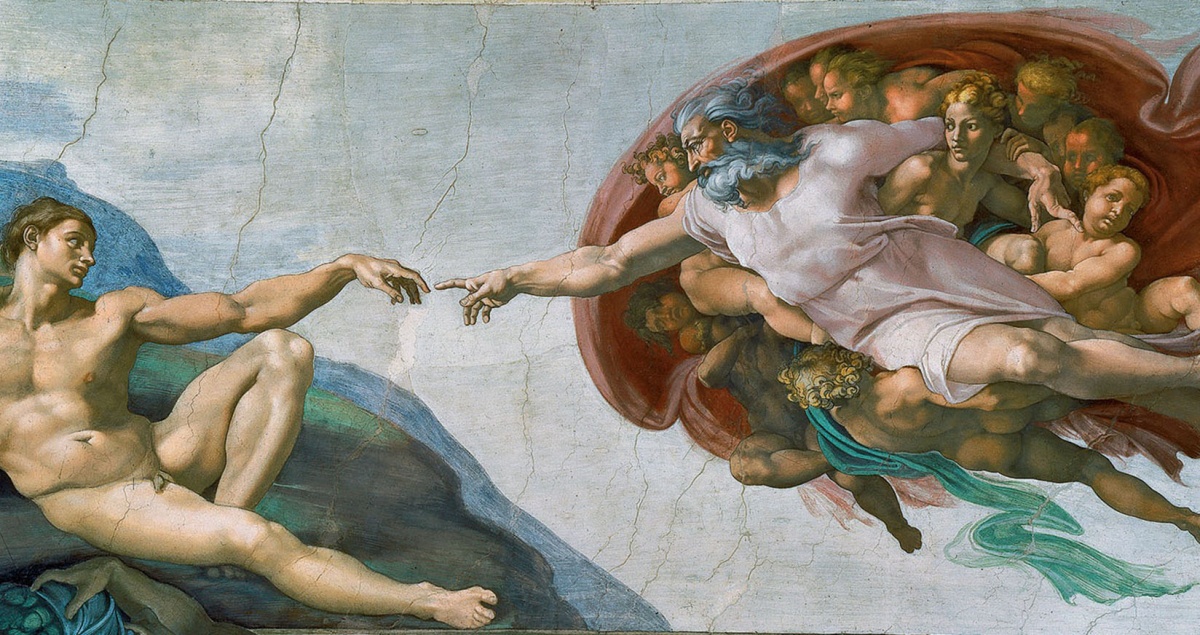

The transhumanist movement represents the ultimate temptation for man to play God and refashion himself as an immortal being free of pain. As Calvin warned, the human mind is a forge of idols.

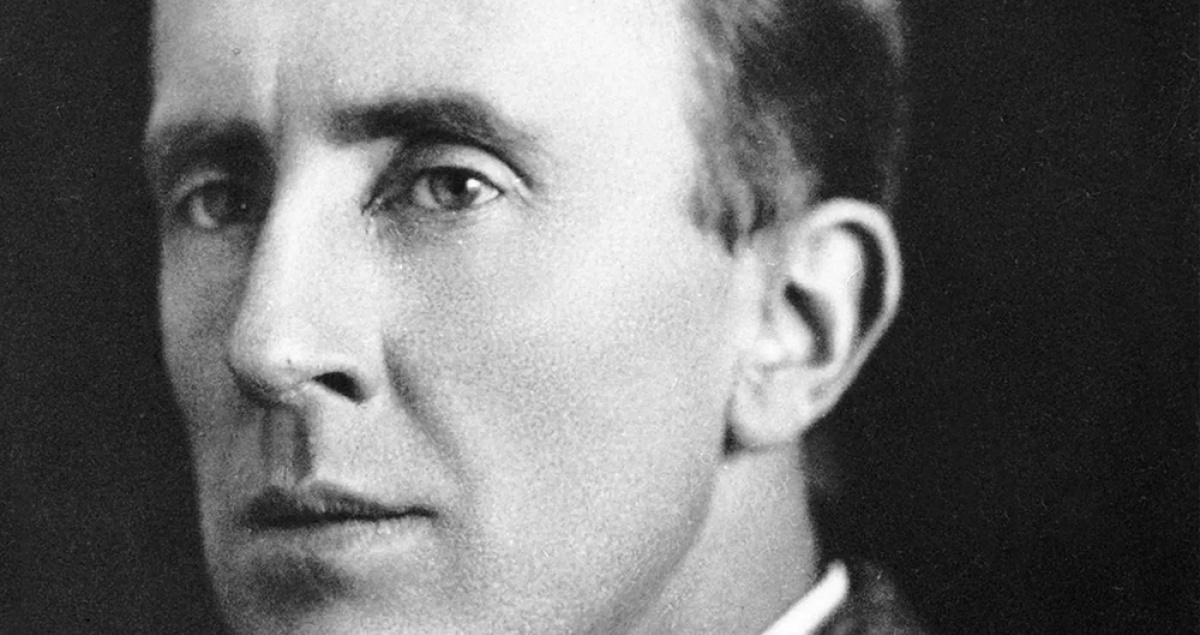

This visionary agenda is not primarily crafted in the academic ivory towers but in an interplay between technological industries, culture makers, and consumers. Many of its key players or supporters are known to the wider world and work in significant institutions, such as futurist Ray Kurzweil (director of engineering at Google), inventor Elon Musk (Tesla, SpaceX, Neural Link, and more), and philosopher Nick Bostrom (The Future of Humanity Institute, Oxford). Some are not as well known but just as important to the project, for example gerontologist Aubrey de Grey and philosopher-futurist Max Moore.

Closely connected with these ideas and aspirations is the growth of emerging technologies, foremost the impressive developments in artificial intelligence (AI). More than that, we are witnessing not only the emergence of technological innovations and applications but also their convergence into new areas of research (foremost the interconnectedness of neurobiology, information technology, computer science, and biotechnology). Such developments—although relatively independent of the transhumanist movement—are taken as promises of the trustworthiness of the transhumanist vision. Absolutely central to this vision is the prediction that in a not-too-distant future, there will be an intelligence explosion, or, as it is also called, a point of technological singularity, when AI first reaches a human intelligence level in all domains of knowledge and then self-improves in order to reach a superintelligent echelon. Such an advanced and autonomous super-AI will acquire abilities beyond the narrow tasks of playing chess and directing cars between two points, since it will drastically exceed human abilities and not be liable to humanity’s many weaknesses. Some predict that once AI has reached human-level intelligence (perhaps even within the next few decades), there will be a very rapid takeoff of ingenuity and mastery of knowledge and practices that will be impossible to control. Such a Superintelligence will be able to establish its own goals and perhaps have its own kind of consciousness. In preparation for such an intelligence explosion, transhumanists advocate that humanity should get ready to upgrade so we may coexist peacefully with other types of intelligences. Furthermore, we should also consider novel ethics challenges, like what moral rights and duties applies to fellow nonbiological intelligent agents.

Transhumanists advocate a blurring of the boundaries between the biological and the technological, the natural and the artificial, and that we should be free to reconstruct “humanity” as we like. This so-called morphological freedom is the freedom to change body and mental makeup by means of technology in any way one wishes. As various enhancement technologies become more generally available, they will change the common perception and future concrete practice of, for instance, medical science so that the distinction between medical treatment of illnesses and medical enhancement will be less clear cut, and one day obsolete. Here we should mention de Grey and Moore again, who in different ways have taken concrete measures to obliterate or postpone their own deaths.

And what’s a revolutionary movement without reactionaries? Anyone who resists this pendulum swing will be branded “bio-conservative” or even “bio-Luddite” by the transhumanists, who argue that leaving “old” biology behind will not be a great loss, because we are not limited to our biological and evolutionary origins by any kind of determinism—divine or materialistic. In fact, our current state as homo sapiens is merely a brief phase in evolutionary history. We are, in other words, facing the possibility of being superseded by a future posthuman species. (Thus the label “transhumanism” is sometimes used to denote the efforts to bring about the intermediary life form between humans as we know them and posthumans.)

Transhumanists argue that leaving “old” biology behind will not be a great loss, because we are not limited to our biological and evolutionary origins by any kind of determinism—divine or materialistic.

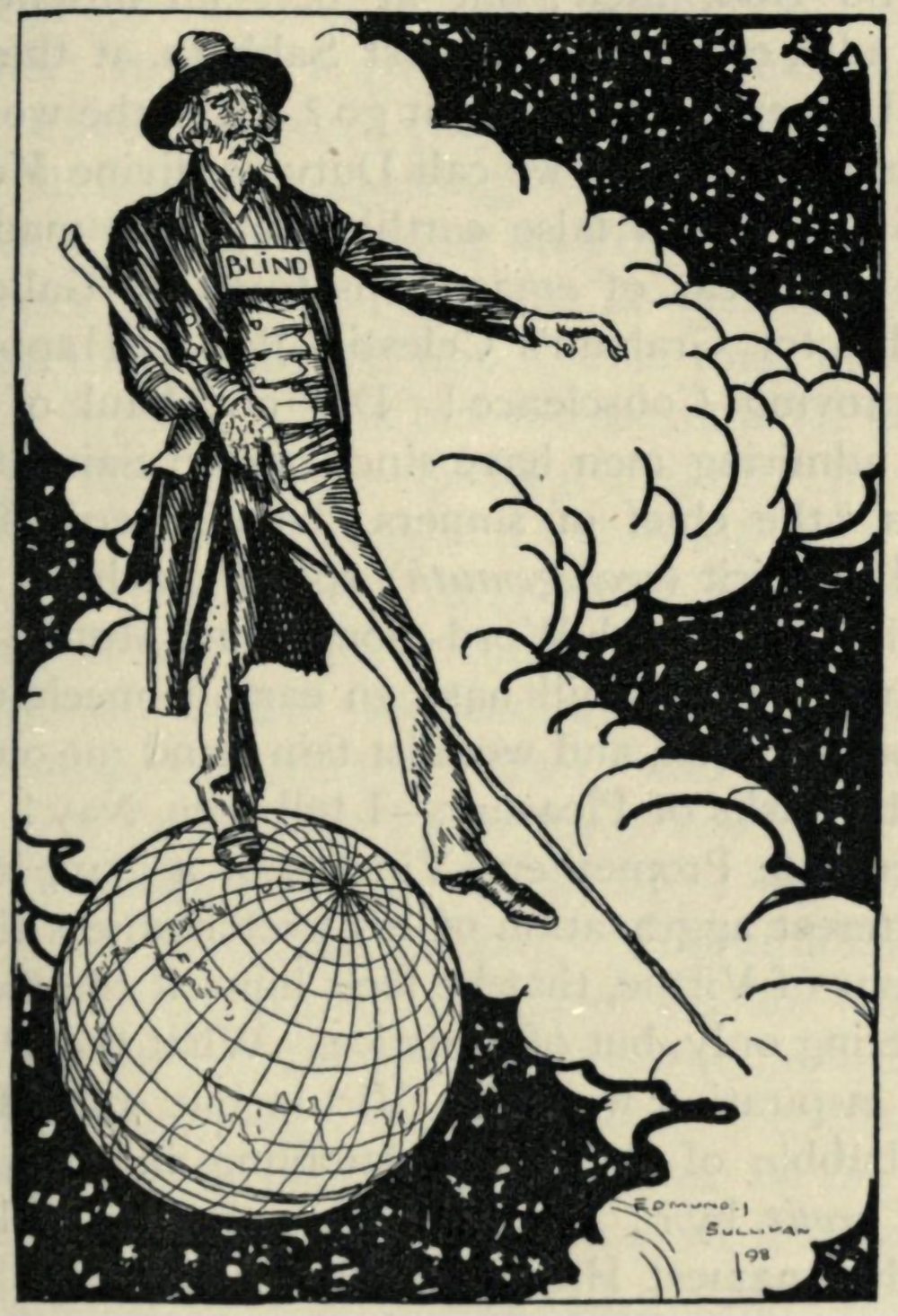

Jacques Ellul and the Technological Society

Objections to transhumanism comes in various forms. Bio-conservatives have sought to defend the claim that there are essential features of humanity that get lost in the transhumanist vision—for instance, the integrity of the natural and the biological, and the gift of finitude, which grants us our species-specific dignity and moral status. (There are also bio-conservatists who argue from a more explicitly leftist-oriented political agenda, saying that enhancement technologies will boost global inequalities, dividing humanity into two classes.) Leon Kass and Francis Fukuyama have argued that enhancement technologies will be equivalent to our “playing God” and a threat to human dignity, as they would manipulate nature in unlawful ways. Some religiously oriented bio-conservatives argue that nature is sacred because it is created by God; obviously, such an assertion is not shared by nonreligious bio-conservatives like Jürgen Habermas.

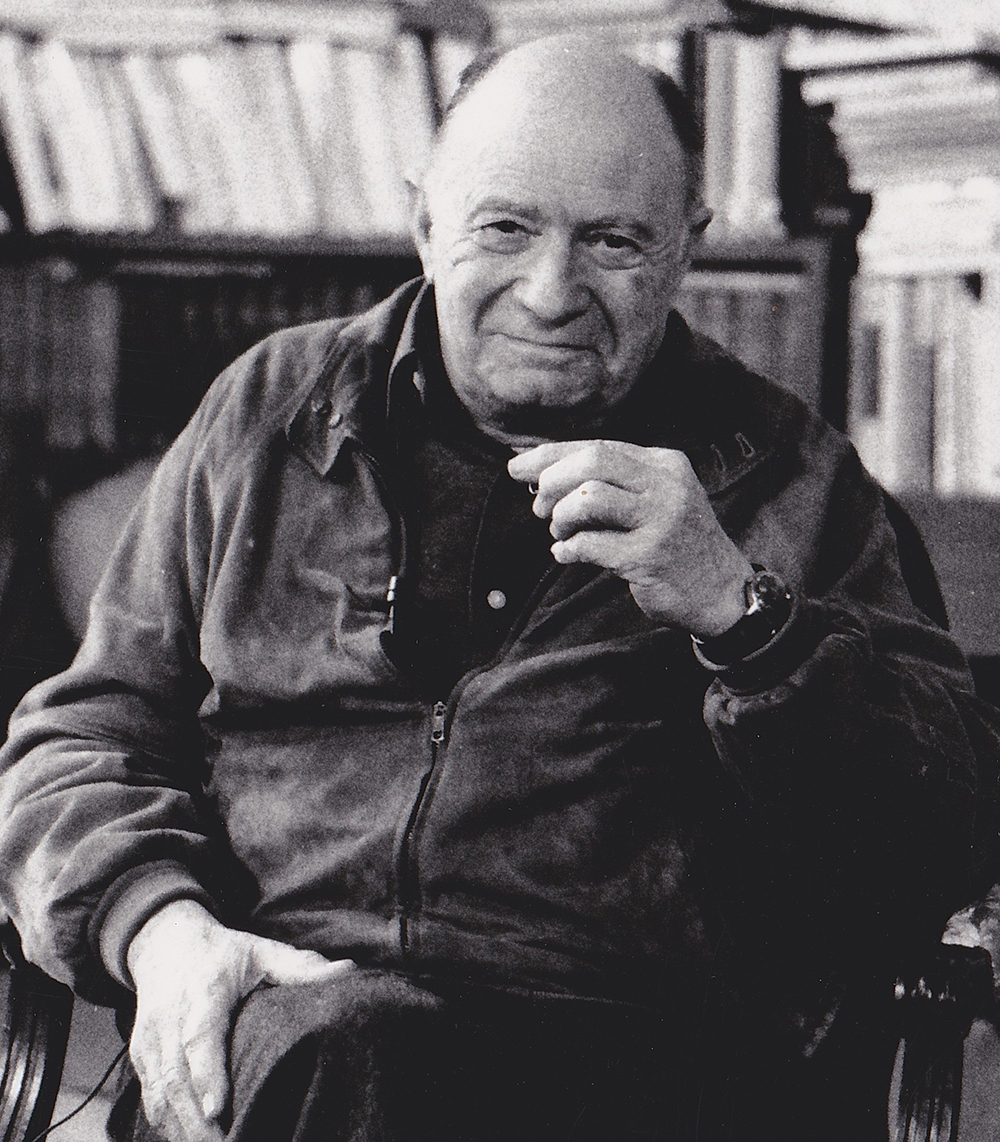

While I think there are ways to defend coherently at least some of the bio-conservative arguments on theological as well as philosophical grounds (e.g., by looking at the metaphysics of persons), that is not exactly what I shall do here. Instead, I will briefly try to say something about the transhumanist vision in an exchange with one of the most energetic critics of modern technology in the 20th century: the French sociologist and lay Protestant theologian Jacques Ellul (1912–1994).

Ellul is occasionally honored with a quote in the literature debating transhumanism, but his ideas are rarely brought into extended dialogue with the themes of transhumanism. There is perhaps reason for this lack of engagement, since he had an aptitude for making sweeping generalizations about problems with modern technologies. (I, too, have my reservations about various aspects of Ellul’s techno-criticism, but I think there are important aspects that should be considered in this debate.) Lutheran theologian Ted Peters, for instance, argues that Ellul was overly critical of technology as such, and points out that any reasonable anthropology would acknowledge that using and developing technologies or techniques is part and parcel of what it is to be human, a homo faber. The real problem is the misuses or overuses of technologies, says Peters. This criticism might be fair as far as it goes, but it also runs the risk of missing the main point of Ellul’s criticism: modern technology is no longer merely an instrument disposable for our use (and abuse) over which we may deliberate rationally and ethically.

Even if Ellul’s (in)famous criticism of our technological culture was severe and sometimes overstated, it reflected a broad techno-critical sentiment among European postwar intelligentsia. Ellul can be said to belong to a diverse group of thinkers including Martin Heidegger, Lewis Mumford, Hannah Arendt, as well as Christian authors J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. They all had a vivid sense of how a relentless technological optimism could just as rapidly destroy as construct, to the detriment of humanity and the biological world. Samuel Matlack, editor of The New Atlantis, captures the zeitgeist of the times: “Utopian dreams comingled with nightmares of terrible ruin.” The thrust of Ellul’s criticism focused on technologies as they have and will shape the possibilities of life. As he put it, modern technology has become a “buffer” between us and nature so that we now are separated from the kind of environment we have evolved to live in. This is, in a nutshell, the problems of technique.

The problems that technique is supposed to solve often arose as a consequence of an earlier technique. The result is a kind of technological totalitarianism.

Ellul’s most famous book on the subject, The Technological Society (written in French in 1954 and translated into English in 1964 on the suggestion of Aldous Huxley), however, is not concerned with any particular technology. The author’s extensive analysis concerns the phenomenon of technique. He begins by making two observations: (1) technique precedes scientific developments, since scientific developments require new methods and techniques; and (2) technique is not to be identified with the machine, yet the machine is the ideal realization of technique. Technique is simply defined as the complex of rationally ordered methods and means for making all human activities more efficient. On the surface it may not sound harmful, but problems arose in the modern period when this innate tendency in human practical rationality began to be applied to virtually all areas of human life and beyond, converting everything into a means to an end. As a consequence, the ends to which the tightly controlled means are directed have been arbitrarily stipulated by the whims and wishes of human societies. The modern methods of technique, so understood, are all-pervasive and have become a complex integrated and autonomous system that has slipped out of the hands of humans so that we are always and everywhere in the hands of technique. It has become its own kind of all-embracing ideology. Ellul points out that for modern people, virtually every problem in every domain of life—from a mere inconvenience to an illness to an existential crisis—is expected to have a technical solution. The irony is that the problems that technique is supposed to solve often arose as a consequence of an earlier technique. The result is a kind of technological totalitarianism that exponentially will—although not by absolute necessity, Ellul is careful to add—continue to shape and control human societies and life.

Ellul gives plenty of examples of how all areas of human and nonhuman life are being subjected to techniques of various kinds—family and population planning, the environment, animal care and agricultural work, economics, politics, and so on. A familiar one is that education has by means of technique gone from teaching skills and facts to efficient methods of passing tests. Not all the examples Ellul gives are grounded in thorough research (some are even anecdotes and drawn from general experience). Some are overstated or misguided (that jazz music is enslaving, for instance). Yet the essence of his analysis is worth paying attention to and appears to be increasingly confirmed by the technologies that have now entered our lives. Today we naturally think of the problem of climate change, which is caused by human overconsumption based on “unsustainable” technologies and is now, at least according a substantial number of politicians, activists and scientists, supposed to be solved primarily by another set of “sustainable” techniques, preferably those that will change our lifestyles as little as possible.

Ellul based his dystopian-future predictions about the technological society on observations from the techno-optimist spirit of the post–WWII societies of the 1950s. Those predictions, not least after the advent of the internet in 1994—incidentally, the same year Ellul passed away—and the advancement in and application of artificial intelligence to various spheres, have at least been partially fulfilled. It is certainly striking that Ellul saw already in the 1950s that there would be a scientific and cultural acceptance of a blending of the artificial and the biological (DNA was discovered only in 1953), which is central to the transhumanist vision of morphological freedom.

However, as emerging technologies gain increasing power to condition and reshape human and other life in all sorts of ways, the transhumanist sees the flip side of Ellul’s dystopian future. Where he perceived illusory freedom and bondage, they predict freedom and individuality.

The Demise of the Acting Subject

Transhumanists welcome a society saturated with and built on technologies, because they believe it will be composed of true “individuals”—be they humans or something beyond human. They will be wholly free to choose their own makeup (physically, mentally, emotionally) and will be liberated from death, boredom, and suffering. Ellul objects that such a vision is not only naive but also fundamentally misguided, since more technique will not make for more or genuine freedom. In a technological society, humans and their successors are not acting subjects anymore but objects of technique. Therefore, they are liable to all kinds of necessities and control, because technique implies that, in the name of rational efficiency, everything becomes a means of impersonal, technical development.

Ellul’s claims about technique have similarities to what today is called “ultimate harm” and “existential risk”—the kinds of harms and risks that can potentially annihilate the conditions necessary for the survival of the entire species. It is exactly these kinds of risks that sober transhumanists (and there are some) try to manage in their pursuit of a safe transposition to a new kind of technological existence. However, since transhumanists value the outcome of a free society so highly and attribute to it the coming of a technological age, they are willing to try to manage the risk by a cooperation between scientists and intellectuals of all stripes. Philosopher Nick Bostrom perfectly embodies the technicist ideal when he argues:

The [philosophical] outlook now [in contrast to the ancient one] suggests that philosophic progress can be maximized via an indirect rather than by immediate philosophizing. One of the many tasks on which superintelligence (or even just moderately enhanced human intelligence) would outperform the current cast of thinkers is in answering fundamental questions in science and philosophy. This reflection suggests a strategy of deferred gratification. We could postpone work on some of the eternal questions a little while, delegating that task to our hopefully more competent successors—in order to focus our own attention on a more pressing challenge: increasing the chance that we will actually have competent successors. This would be high-impact philosophy.

We may say that Bostrom’s “high-impact philosophy” is one that has been subject to and transformed by technique, which, on Ellul’s analysis, implies that it has traded its freedom for efficiency. Put differently, the virtue of perennial wisdom is replaced by a sort of smart utilitarianism.

No Free Choices?

Modern people are culturally conditioned to think they are freer than previous generations, in large part due to the blessings of sciences and technology in their everyday lives. Admittedly, we are generally enjoying a materially more comfortable life than did our forebears, but we are also beginning to be alerted to the problems involved in this kind of life. I have already mentioned climate change but numerous examples can be drawn from the way smart technologies and social media affect us. For instance, there are endless possibilities for self-expression by way of social media, but we have also become increasingly aware of being “owned” and conditioned by the big tech companies and billionaire CEOs. But a dim awareness is not to be confused with an insight into our state that will lead to action, at least not for most individuals. Moreover, according to Ellul’s analysis, those very big tech elites are equally determined by the technology they produce. In fact, in a technological society, there is no longer a controlling elite, because politicians, journalists, technicians, and philosophers (which is to say, government, media, big tech, and the academy) are also defined by—and perhaps in the end replaced by—the perfection of technique: the machine.

By extension, then, even the individual or corporate choice to enter a transhumanist existence is not a free choice. Even less free are the individual and corporate choices involved in such an existence. With the emergence of the Janus-faced artificial human intelligence, at some point morphing into superintelligence, the rendering of what constitutes “individuality” will be determined by a superior technological power whose goals we may not be able to predict or understand. It has been suggested that perhaps the goal for a Superintelligence is to produce an infinite number of random objects, like paper clips. Then everything will serve that arbitrary end-as-means, humans included. (Think humans as “batteries” in The Matrix films.) This suggestion is supposed to highlight the potential dangers of letting an unharnessed artificial intelligence loose in the world. The transhumanist future hope is thus very fragile.

Despite these hypothetical risks, let us grant, for the sake of argument, that should humanity survive the supposed point of singularity, when artificial intelligence exceeds human intelligence, enhancement technologies will bring high and stable degrees of happiness, physical strength, and perceptive awareness to transhumanist individuals. However, such enhanced features are not unequivocally identical to a heightened individuality or autonomy according to Ellul’s basically personalist analysis. He remarks: “When Technique displays an interest in man, it does so by converting him into a material object,” and man will be guaranteed the kinds of “material happiness as material objects can [guarantee].… But the technical society is not, and cannot be, a genuinely humanist society, since it puts in first place not man but material things.” Ellul is convinced that human or “spiritual” excellence and progress is not reducible to technique. Conversely, material development is not identical to spiritual or intellectual maturation. (Ellul here has an argument with both the capitalist and the Marxist visions of well-being, which were clearly displayed in the postwar European scene.)

We have become increasingly aware of being “owned” and conditioned by the big tech companies and billionaire CEOs. But a dim awareness is not to be confused with an insight into our state that will lead to action.

In the last chapter of The Technological Society, Ellul cites some proto-transhumanist futurists. One of them enthusiastically claims that humanity will be able to have “emotions, desires and thoughts” modified, and so produce “a conviction or impression of happiness.” Interestingly, Ellul’s response bears striking similarities to Robert Nozick’s famous thought experiment, “The Experience Machine” (1973), directed against the unlimited hedonism of utilitarianism (“pleasure is good”). Imagine that a machine can manipulate a human being so that she experiences a simulated reality that feels perfectly real and can produce unlimited positive emotional input. What reality would you choose to live in? This absurd example was supposed to be a reductio against utilitarian hedonism, since Nozick assumed that rational people would choose to live outside the machine, despite being liable to boredom and suffering. However, this kind of objection is not particularly effective against the transhumanist intuition that already accepts, ideologically, the idea of technological absolutism. To many transhumanists, a simulated reality is just as much a reality as what we ordinarily call reality. Thus, there is no significant distinction between living in or outside of the Matrix, since intelligences or persons are fundamentally nothing more than patterns in an information flow that can exist biologically (wetware) or on a silicon substrate (hardware). Indeed, the idea that we live in a machine already (created by technologically superior intellects in a distant past) is something that Nick Bostrom et cohortes argues is more likely than not. Here we hit the bedrock of competing intuitions about reality. However, on Ellul’s analysis, this is to be expected in a technological society where the values of techniques have become so deeply engrained that reality is essentially a technological simulacrum.

A New Religion for a New Age

Although there are some religiously inclined transhumanists, like aforementioned Ray Kurzweil or sociologist James J. Hughes, transhumanism is basically a secular movement. Yet it has been characterized—and I think fairly—as a form of “secularist faith,” since it promotes a vision of the “good life” and “pious” practices similar to those taught by traditional religions, although with radical differences. I believe that transhumanism, in soteriological terms, is essentially “Pelagian,” since “salvation,” a new kind of “eternal life,” is strictly in the hands of human beings. Technology is the “divine” power that will deliver the goods, and humans are responsible for bringing about the technological heaven on earth. However, when technology is given such authority, it both leads to human domination over creation and puts an enormous weight on the ability of humans to shape their own and the world’s destiny. As theologian Norman Wirzba points out in The Paradise of God: Technique (Techne) in the antique was the human way of working with the inherent order and reason (Logos), whereas the modern combination of the two—technology—is the exaltation of human intelligence as the order of things. Ellul teases out the spiritual consequences:

The individual who lives in the technical milieu knows very well that there is nothing spiritual anywhere. But man cannot live without the sacred. He therefore transfers his sense of the sacred to the very thing which has destroyed its former object: to technique itself. In the world in which we live, technique has become the essential mystery.

This is nothing short of idolatry in theological terms. It is surprising, however, that Ellul did not write that the sacred is eradicated. He could have claimed that at the arrival of the “machine-man,” secular technique would have done away with the need of mystery—God and religion—in all its forms. But he did not, because his anthropology reflects the Christian basis of his thought, which is radically different from the austere materialism of many thinkers in the postwar period. As I have hinted above, I think we should understand Ellul as a personalist: He is convinced that the human person is an irreducible category of reality. Reducing persons to matter is by the same token reducing their freedom and status as imago Dei. As a Christian, Ellul is well aware of the effects of sin. It may be said that his analysis of the phenomenon of technique is an analysis of sin as bondage to created goods and gods, of how the mystery of God as telosmigrates and becomes the “mystery” of created means.

In a wider sense, substituting the created for the Creator is symptomatic of our human condition and not merely a modern problem. As Calvin famously put it, the human mind is a factory of idols. The transhumanist vision can function as a way to survive the loss of religion, since it bears a superficial resemblance to religious themes. It thus offers a sort of hope to people who are losing their faith in religion but nevertheless cling to new forms of spirituality.

Christians are not immune to such temptations, as they are implicated in a technological society. To live faithfully in a world increasingly determined by technology, one needs to be observant about the myriad ways in which one is buying into materialist visions of the present and future at odds with classical Christian anthropology and eschatology.

The Apostle Paul exhorted the early Christians in Rome to practice discernment in pursuit of God’s will for their time and to be transformed by the renewal of their minds (Romans 12:1–2). This is an exhortation for our own day, too. Ellul’s prophetic analysis of technique is helpful for a vigilant life in face of the particular temptations of idolatry today. Although Ellul at times can sound a bit romantic about premodern life, he never advocated a nostalgic return to a pristine age but urged us, by the grace of God, to live well in the here and now with a sober and supernaturally grounded view of the future.