“Like religion, education is nothing or it is everything—a consuming fire in the bones.”

—Charlotte Mason

During World War Two, as the Allies endeavored to win the war against the Axis Powers, Christian humanists were looking to the future: If U.S. guns helped turn the tide in the war, how then would the peace be won? How could the Allied nations avoid becoming like their enemies? As French writer and mystic Simone Weil put it during the Nazi occupation of France, “If we are only saved by American money and machines, we shall fall back, one way or another, into a new servitude like the one which we now suffer.”

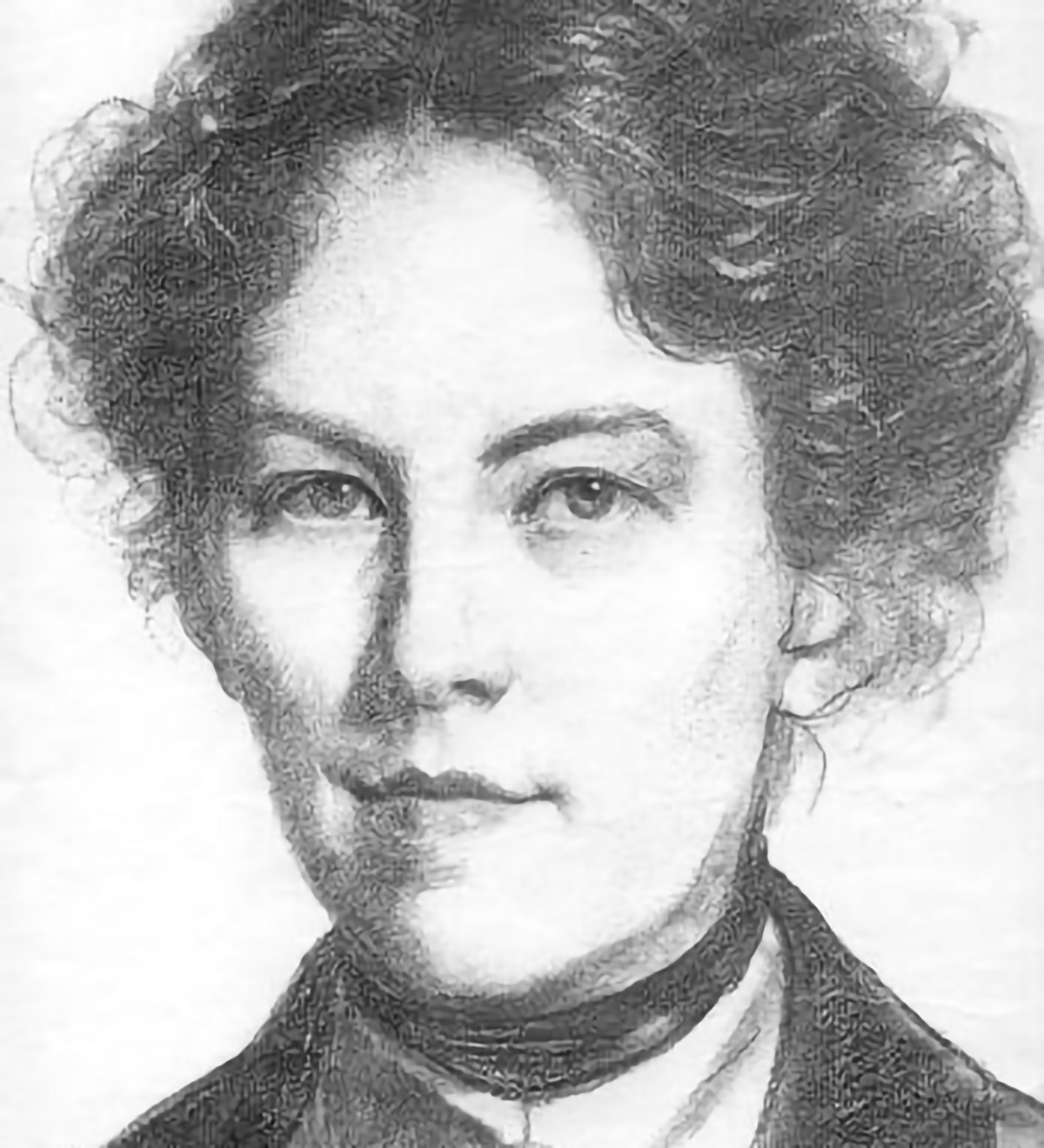

Long before the modern homeschooling and classical education movements, a British schoolmistress discovered and applied a “living” philosophy of education and pioneered “a liberal education for all.” She began, and ended, with what it means to be human.

In The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis, Alan Jacobs tells the story of five writers—C.S. Lewis, W.H. Auden, T.S. Eliot, Jacques Maritain, and Simone Weil—who concerned themselves with what kind of Christian formation the postwar world would need. They wanted “to reshape the educational system of the Allied societies in a way that would both respect and form genuine persons.” Jacobs tells the story of how their task failed; the foundation had already been laid for the rise of technocracy, and modernization quickly squelched any vision of nationwide educational programs based on a Christian understanding of the world.

Simone Weil, for example, endeavored to articulate a vision for France if it were ever freed from German occupation. She wrote The Need for Roots in 1943, dying before she could finish the work or see the end of the war. In this work, she pushed back against the realpolitik that treated human beings like things rather than persons. The combined effects of what she termed la force—that which “turns anybody who is subjected to it into a thing”—and affliction, or malheur, the uprooting of the soul, provided a dual challenge for her educational vision. Here she parallelled C.S. Lewis’s critique of the modern world in his Abolition of Man: “We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful,” he famously wrote. That is, our modern world still expects virtue from men while removing the means of formation toward virtue.

“To show what is beneficial, what is obligatory, what is good—that is the task of education,” wrote Weil. But education must also cultivate the habit of pursuing the good. Jacobs notes that Weil provided a “diagnosis without a prescription—or, to be more precise, a prescription without the delivery system.”

Lewis’s and Weil’s critiques are even more important today than when they were first written. But the project theorized by all five of those thinkers, especially that of Simone Weil, had already been developed by a British schoolmistress who had died in 1923 and counted G.K. and Frances Chesterton as friends.

In 1901 The Parents’ Review, the journal of the Parents’ National Education Union (PNEU), included a notice that Frances Blogg had resigned her position as PNEU secretary. That June she would become the bride of Gilbert Keith Chesterton. Frances and her husband would continue to be comrades-in-arms with the PNEU and its founder, Charlotte Mason, defending the integrity of the human person against a brave new world in thrall to the intellectual fashions of the day, whether they be eugenics, scientific materialism, or totalitarianism.

Charlotte Mason was born in 1842 in Wales to a Catholic mother and a twice-widowed Irish Quaker father. Early in her life she undertook the vocation of a teacher and began a lifelong study of the human person, which she articulated in six volumes of educational philosophy.

When Mason first began teaching, there was not yet compulsory public education (the Elementary Education Act in England and Wales would come in 1870). Children then were educated variously, through parents, governesses, Sunday schools, boarding schools, or a mixture of these—or they had no education to speak of.

Mason trained young women to be teachers but also to learn what it meant to be a person themselves.

Over the course of her life, Mason would found many schools for children and teachers and oversee the PNEU—an association of parents and others who carried out her philosophy in their homes and communities. Mason’s principles eventually spread to elementary and secondary schools, which were termed “PNEU Schools.” She herself ran the House of Education, a school for teachers. The PNEU ran natural history clubs and a three-year mothers’ education course (the reading list included Plato, John Ruskin, and Coleridge, as well as Bible commentaries, nature lore, and Mason’s own work). It also played host to many talks followed by discussions, often in members’ homes. (Sometimes Chesterton himself would lecture at PNEU meetings.)

At the House of Education in Ambleside, England, Mason trained young women to be teachers but also to learn what it meant to be a person themselves. Thus a new student at Ambleside might find herself learning to observe nature more keenly, to take delight in naming the birds that awakened her with their song in the morning, and to brush-paint what she observed. She might find herself studying from perhaps unusual textbooks—not only foundational texts like the Bible and the works of Plato but also newer works like Lord Baden-Powell’s Aids to Scouting. (Baden-Powell would later honor Mason as a crucial encouragement for beginning the worldwide scouting movement for boys and girls.) A student at Ambleside would also learn to narrate: to make her own what she read and saw and experienced in books, art, music, handicrafts, and nature.

Yet much of Mason’s attainments were lost with the modernization of education and societal shifts after the Second World War. In the 1980s, however, her six volumes on education were rediscovered and have since inspired homeschoolers and private schools around the world—including an association of schools named after her own Ambleside, England. Indeed, Mason is claimed as a forerunner of both modern homeschooling and the classical education movement. But her philosophy of learning-as-delight continues to offer deeper riches for our time to uncover. In this essay I will focus on three.

In contrast to armchair philosophies and spreadsheet fads, Mason offers (1) a practical, tested philosophy of education based upon decades of experience with children of different classes, abilities, and cultures; (2) an articulation of personhood, rooted in the classical Judeo-Christian tradition, that avoids both reductionism and sentimentality; and (3) a challenge to our society as to how we may better conceive of and live out the complexities of communal and political life—that is, our life together.

Of the 20 principles that sum up her educational philosophy, two are fundamental: “Children are born persons” (her very first principle) and “Education is the science of relations” (which undergirds all the remaining principles).

It is important to note that Charlotte Mason never called her philosophy by her own name. Indeed, she emphasized time and again that she did not create the principles she outlined but rather discovered them. “I have not made this body of educational thought any more than Columbus made America,” she wrote in a 1904 letter:

But I think it has been given me to see that education has a triune basis, to recognize that education is the science of relations, to perceive certain working theories of the conduct of the will and of the reason, to exact due reverence for the personality of a child (I mean the reverence of educational practice, not of sentiment), and some few other matters which go to make up a living, pulsing body of educational thought.

Beginning with the idea that children are created in the image of God, she endeavored to articulate a practical philosophy that truly lived out the idea that every human being is a person meant to flourish in this life.

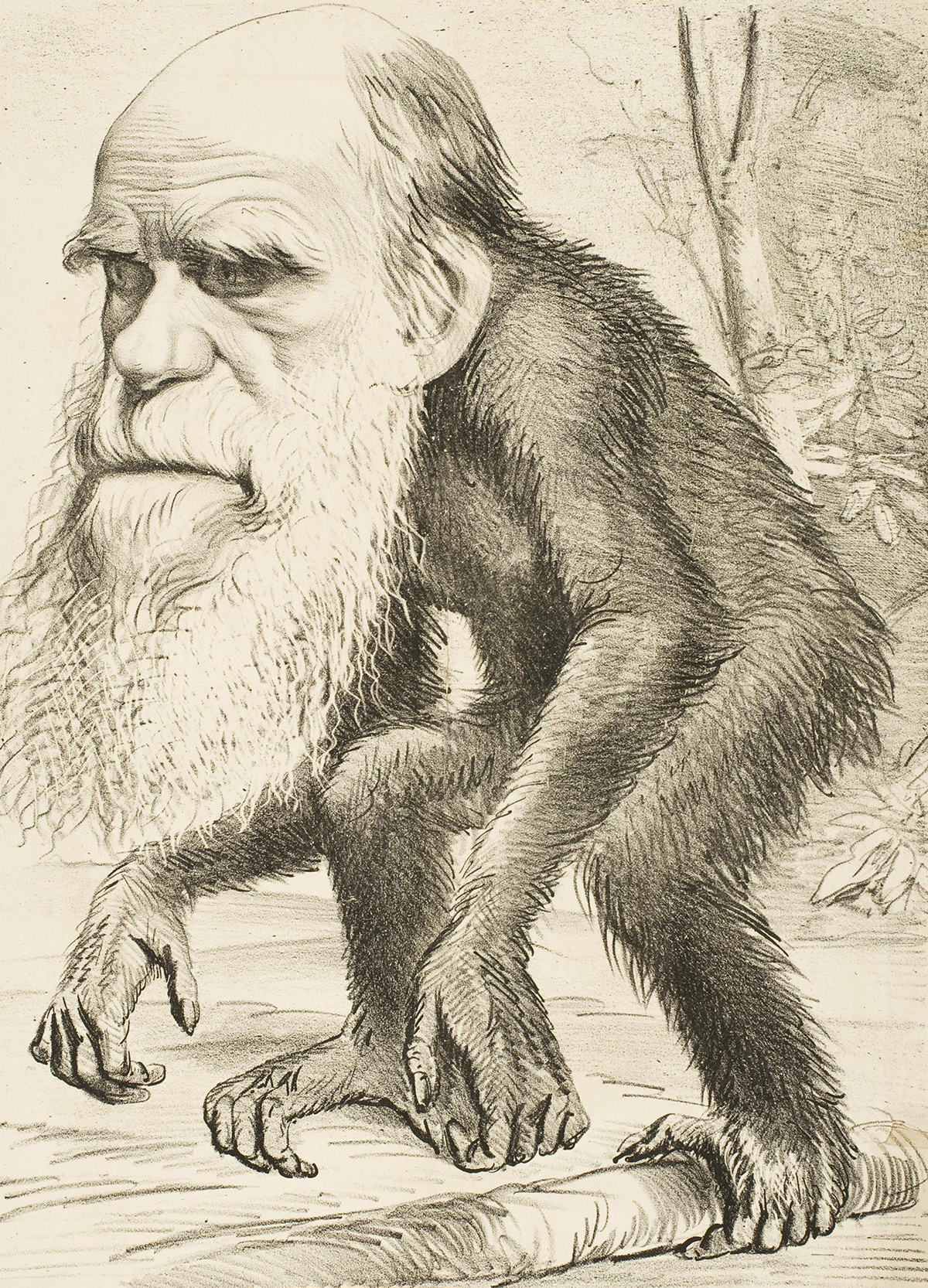

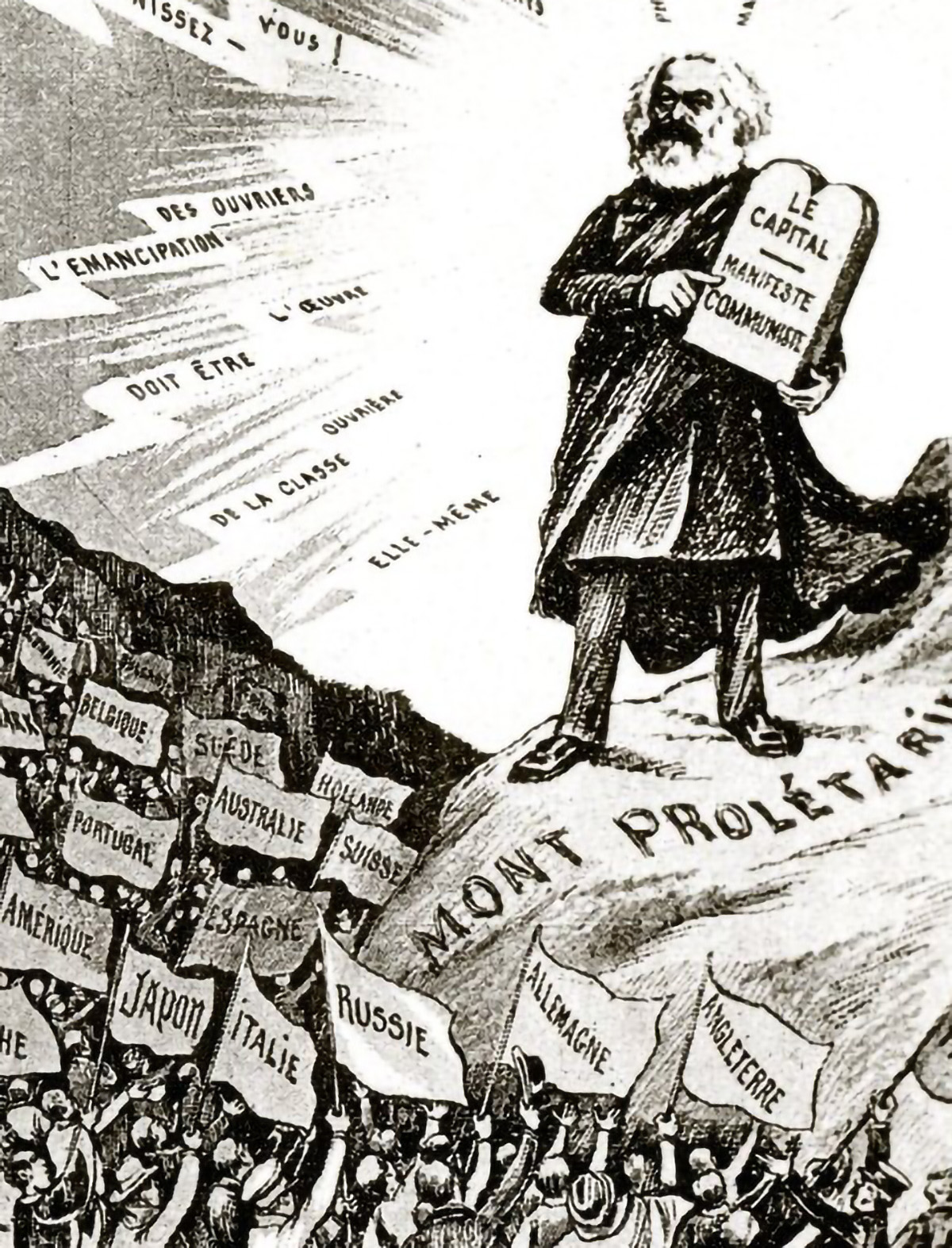

The very idea of the human person and of the uniqueness of human nature were contested ideas at the turn of the 20th century, as they are today. In Mason’s own lifetime, Marx and Engels’s Communist Manifesto was published (1848); Darwin’s Descent of Man arrived (1871); Lenin led the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II to pursue a revolutionary ideology (1917); and Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams was published in its original German (1899). In addition, the historical-critical method of interpreting Scripture was presenting challenges to the faith of ordinary churchgoers, and the Second Industrial Revolution was remaking ordinary life, introducing widespread electrification, telegraph-quick communication, the continued growth of factory systems, and the motorcar. “Progress” in technology accompanied regress in a coherent appreciation of the human being, in addition to increased uncertainty as to what it meant to be human.

Amid this anthropological, theological, and political upheaval, this single woman began to articulate a philosophy of education for all children—one rooted in the understanding that what it means to be a person was fundamental to any educational endeavor.

An essential part of personhood is to be endowed with a glorious mind—the living, generating spirit or soul of a person.

An essential part of personhood, Mason believed, is to be endowed with a glorious mind—which for her meant not mere intellect but something rooted in what the medievals called intellectus, a deep and intimate knowing. Mind for Mason is the living, generating spirit or soul of a person. And just as the body needs good food, so the mind must be fed on living ideas. She defined an idea—drawing on “the older philosophers, from Plato to Bacon, from Bacon to Coleridge”—as a “live thing of the mind.” The child, then, should feast upon a generous variety of ideas. She insisted, moreover, that every person—child and parent, miner and merchant—was heir to the best that has been thought and said. Hence her rallying cry, “A liberal education for all,” irrespective of class, ability, or background.

She admonished her own age for “despising the children”—that is, treating children (and hence, the persons they would grow up to be) as less hungry for knowledge, beauty, and truth than they really are. Children are neither mere sacs for information, machines to be programmed, nor blank slates to be written (and rewritten) upon according to our wills, she argued. In her volume School Education, Mason cites a “wise sentence of Coleridge’s” that articulates how Plato himself educated:

He desired not to assist in storing the passive mind with the various sorts of knowledge most in request, as if the human soul were a mere repository or banqueting room, but to place it in such relations of circumstance as should gradually excite its vegetating and germinating powers to produce new fruits of thought, new conceptions and imaginations and ideas.

These words, she writes, “should be always present to the minds of persons engaged in the training of children.”

The mind of a human person is unlike anything else in creation—it is, in Karen Glass’s phrase, a “spiritual organism.” Too often Mason saw children’s minds underfed, their spirits shriveled through want of great ideas—and too many dry or condescending textbooks—to feed on. Indeed, her educational method was meant precisely to prevent the soul-deserts C.S. Lewis would write of in his Abolition of Man.

And if children are meant to feast intellectually, it is crucial to understand that every child has a natural desire for knowledge. An easy demonstration is the multitudinous questions children ask as soon as they’re able to put together sentences. Even before language, however, a child is constantly learning, constantly endeavoring to discover more about the world around him. It is this natural curiosity that is the basis for beginning the work of education.

This leads us to a crucial point for Mason: We do not need to teach children how to learn, just as we do not teach them how to digest. A full realization of this truth revolutionizes what it means to educate. From the very beginning, children should be fed good food—indeed, the best that can be had, physically and intellectually/spiritually (for we cannot separate the intellectual and spiritual when it comes to living ideas). From the beginning of life, a child is searching for truth, is delighted by beauty, and is moved by goodness, and is continually forming relationships with the world around him. This process only grows more intricate as the child grows.

We often mistakenly assume that children are naturally interested in the equivalent of baby food rather than of hearty meals. For example, ordinary children of eight or nine, Mason believed and witnessed, could appreciate Samuel Johnson’s Rasselas as well as Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Spenser’s Faerie Queene. (My own very ordinary seven- and nine-year-olds appreciate Shakespeare’s plays, Longfellow’s Song of Hiawatha, and Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes.) What children need, she declares, “is to be brought into touch with living thought of the best, and their intellectual life feeds upon it with little meddling on our part.” Just as with food, if a child is given good fare, he responds to it and becomes more and more delighted by it. So, too, a diet of junk food ideas will make a child less capable of appreciating living ideas.

But too often we “despise the children,” giving them, in our modern context, too much screen time to make them be quiet (and more controllable), or we crush their natural desire for knowledge by overplaying other natural desires, such as for praise and gain. And it’s understandable why we resort to marks, grades, and numbers to provide both motivation and evaluation—they are easy, controllable. “Nothing is so clear and so simple as a row of figures,” Mason wryly notes.

It’s precisely this desire to control children rather than do the harder work of guiding and instructing each soul into its full potential that we must resist. Rather, we must allow for the cultivation of an immense web of intimate relationships with other persons and living ideas. A child, Mason writes, “has natural relations with a vast number of things and thoughts: so we train him upon physical exercises, nature lore, handicrafts, science and art, and upon many living books.” The work of education is to cultivate these relations on every level of the person: body, mind, soul.

Included in this work is the one whom Mason viewed as the first and ultimate educator: the Holy Spirit. This is her “Great Recognition,” that parents and teachers educate in cooperation with God. Stratford Caldecott got it right in his Beauty in the Word when he observed Mason’s “refusal to strip grace away from nature” and her understanding that “children possess a spiritual life and that this is the most important dimension of their being—the source of their freedom and happiness.”

Plato famously conceived the ideal city in The Republic, and it is commonly understood that what he says of the properly ordered city goes also for the human soul.

Charlotte Mason also treated the human soul as a polis—a kingdom, in her case. Her fourth volume, Ourselves, Our Souls and Bodies, was meant to be read by students themselves, starting at age 12. In it she describes the government of the Kingdom of Mansoul. Like Plato, she delineates the cardinal virtues and what obstacles endangered the unity of the soul. And like Plato, she taught her students to be philosophers—and for them to teach budding philosophers in their turn. To love wisdom is not merely to seek out head-knowledge but truly to live in that wisdom.

But to understand the soul as a kingdom, with its inherent hierarchy, we must also understand authority—a fraught topic in this age if ever there was one.

Chesterton wrote that he believed Mason’s “remarks on authority” to be “the most original and important part of her work.” And indeed, with the lines “The family government [is] an absolute monarchy” in the beginning of her second volume, Parents and Children, Mason strikes hard against cherished notions of modernity. “No parent,” she continues, “escapes the call to rule.”

But how to get beyond the apparent paradox that authority and obedience are, as Mason explains, “natural, necessary, and fundamental” on the one hand, while the personality, or personhood, of each individual child is to be respected? How is this to be understood, let alone lived out?

There is always a pendulum swing in societal movements (and perhaps more so nowadays, when we have more experts than ever and fewer knowledgeable elders to draw upon). In Charlotte Mason’s day, the flow was toward a theory of child-rearing that reacted against the previous generation’s strict “seen but not heard” policy, against a too-stringent bearing of authority. So parents wanted to be gentler, more soft-spoken, more tolerant. (Sound familiar?)

In this context, Mason examined the previous authoritarian regime of parenting with its “arbitrary rule,” noting both its good points—it could and did turn out “steadfast, capable, able, self-governed, gentle-mannered men and women”—and its flaws, which derived from a wrong idea of authority.

Mason distinguished between authority and tyranny, obedience and servility. What makes rule tyrannous or obedience servile depends upon a false idea of authority or an abuse of that authority (which may add up to the same thing). Whereas in an earlier time, “We believed that authority was rested in persons,” it made sense for rule to be exercised arbitrarily, and for obedience to be slavish. But God’s rule is not arbitrary, and neither is proper human authority. First, human authority is always delegated authority, never ultimate. Only God possesses ultimate authority. Second, proper authority is “vested in the office and not in the person, [and] the moment it is treated as a personal attribute, it is forfeited.” It is the respect due the office that we give the person invested with that office, rather than because of any virtue of the person himself; on the other side, when we take up an office, our duty is to fulfill that office properly: Every person in authority is also under authority, and hence “holds and fulfils a trust.”

What makes rule tyrannous or obedience servile depends upon a false idea of authority or an abuse of that authority.

To assert oneself, and to govern autocratically and arbitrarily, is to misuse that trust. “The despot rules by terror,” Mason writes. “He punishes right and left to uphold his unauthorized sway.” The person “vested with authority, on the contrary, requires no rigours of the law to bolster him up, because Authority is behind him; and before him, the corresponding principle of Docility.”

The upshot is that we will “encroach upon” the personality of a child—“whether by fear or love, suggestion or influence, or undue play upon any one natural desire”—if we do not get these fundamental principles of authority and obedience right, because we are built for authority and obedience. And every authority is answerable to a higher one—and on up to the ultimate Author of all. We must take on the task of ruling well in whatever office we’ve been given—and this includes our rule of the kingdom of our own souls.

The mystery of a person is indeed divine, and the extraordinary fascination of history lies in the fact that this divine mystery continually surprises us in unexpected places. Like Jacob we cry, before the sympathy of the savage, the courtesy of the boor: “Behold, God is in this place and I knew it not.” We attempt to define a person, the most commonplace person we know, but he will not submit to bounds; some unexpected beauty of nature breaks out; we find he is not what we thought, and begin to suspect that every person exceeds our power of measurement. (Charlotte Mason, “Concerning Children as ‘Persons’: Liberty versus Various Forms of Tyranny,” The Parents’ Review, 1911)

Here is where Charlotte Mason’s work is perhaps most pertinent to our day: Every aspect of her philosophy is based upon the irreducible mystery of personhood, and hence is inherently resistant to the idea that humans can, and ought to, be put into a box. At its worst, our education system aims effectively to churn out servile, homeless robots. And even in classical Christian schools and homeschooling cooperatives, we can easily reduce the work of education to producing men and women who can diagram a Latin sentence and score high on tests but who do not love beautiful things and cannot distinguish between tools that ennoble and tools that demean.

But most importantly, Mason outlined how to live out such a philosophy and then lived it out. She didn’t merely theorize or wander peripatetically with her devotees but tested her theories by the Great Tradition and by decades of practice. As one of her students and colleagues, Miss E.A. Parish, noted when she visited a school of 350 in a poor mining district in Yorkshire that had recently undertaken to experiment with Mason’s applied philosophy:

In the schoolroom I found the most utter peace that I have ever found in my life. It was the realization of the hopes we have been cherishing of supplying the children of the less privileged classes with mental food which they can digest. I realized that the mind is the same thing in every human being, and that the mind of a little child which is born to the most ignorant man is open to the great things of the spirit.

Schools and homes both in Great Britain and overseas took on their own experiments, and as another teacher wrote: “Let us ask ourselves, is it a miracle which has been performed in this little school and in others?—I think it is a miracle” (recounted in Essex Cholmondeley’s The Story of Charlotte Mason).

Mason was no armchair educator but was always refining in the trenches. And her principles changed not only the children who went through her schools and the teachers and governesses she trained, but also the families and communities of which they were a part. Indeed, they are practices that work for persons of every age in every age.

And if the soul is a polity, then a healthy polity will in turn reflect the well-ordered soul.

Here is our challenge, then: If everyone in our society is born a person; if we are meant for a complex web of relationships with other persons, ideas, places, stories; if authority and obedience (properly understood) are natural principles in human life; and if human personalities ought not be violated by manipulation or undue influence, how might we envision political life—that is, how might we better live together? How might we change how we treat our employers and employees, our family and neighbors and descendants? What if we truly lived as if the riches of our inheritance, from birdsong to Bach, were for everyone, at every stage of life?

Indeed, how might we live if we desired the following life for ourselves and our neighbors?

Life should be all living, and not merely a tedious passing of time; not all doing or all feeling or all thinking––the strain would be too great––but, all living; that is to say, we should be in touch wherever we go, whatever we hear, whatever we see, with some manner of vital interest. … The question is not––how much does the youth know? when he has finished his education––but how much does he care? and about how many orders of things does he care? (School Education)

Finally, perhaps the greatest witness to Charlotte Mason’s philosophy is Mason herself. The testimonies of her students and friends attest to how she lived out the idea that everyone is born a person and that everyone deserves a feast of living ideas.

A young Frances Blogg Chesterton was impressed with Charlotte Mason upon their first meeting, on “a certain Sunday in Advent” at Ambleside. Frances had just been placed as secretary of PNEU when she attended an afternoon talk by Mason that stayed with Frances for decades afterward. Mason’s ideas did not inspire one just for the moment, but took hold in one’s life and bore fruit—just as living ideas ought. Central to Mason’s work in “true education,” Frances noted, was the fundamental principle of the “intense value of every human soul,” which led Frances to believe that “nothing of God’s gifts given direct by God Himself, or through the instrument of his creatures, could be too good for it.”

In closing, I cannot think of a better way to sum up Mason and her work than with this short anecdote. One young teacher came to Ambleside to be interviewed by Mason. When asked why she had come, the young woman answered, “I have come to learn to teach.” She never forgot Mason’s gentle correction: “My dear, you have come here to learn to live.”