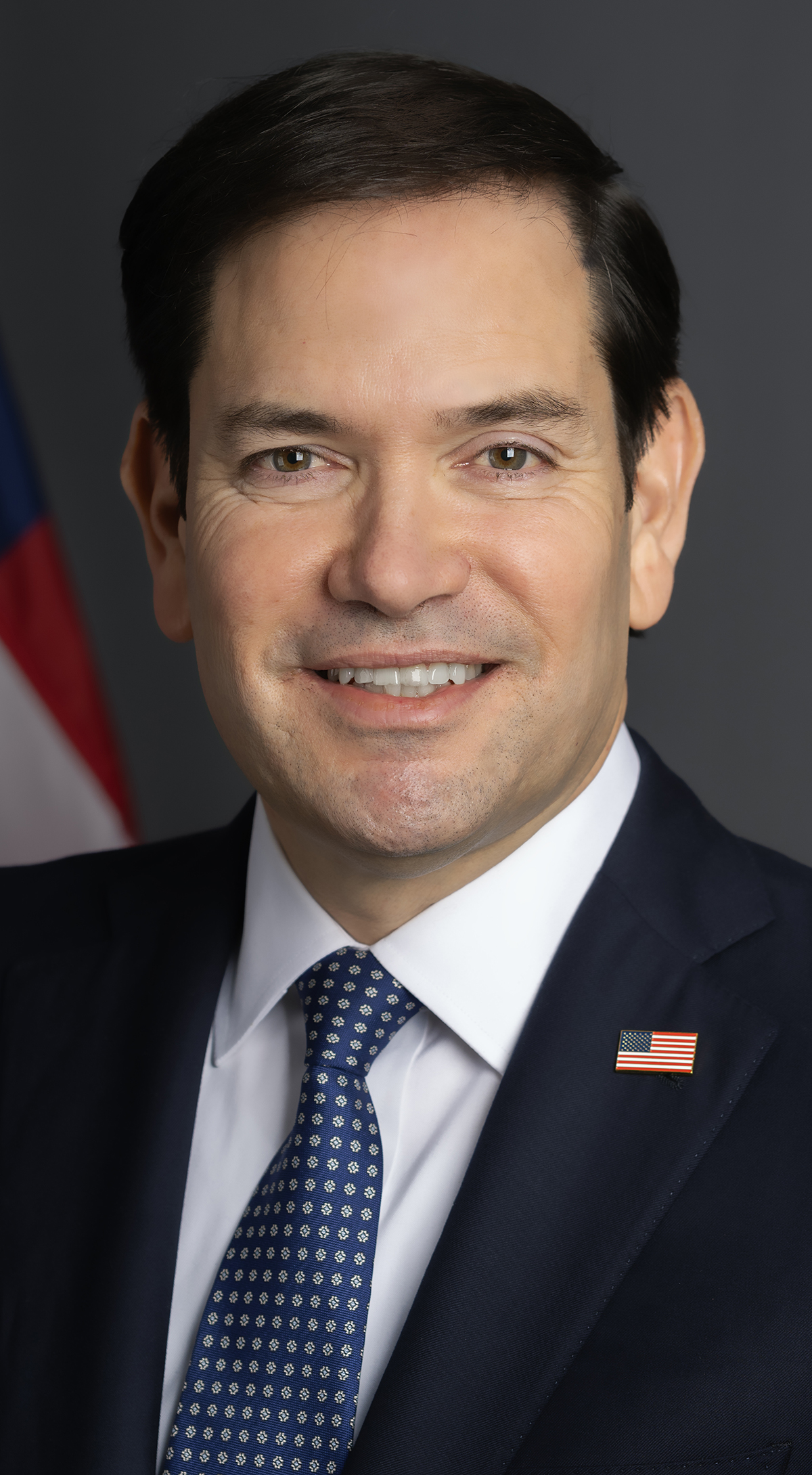

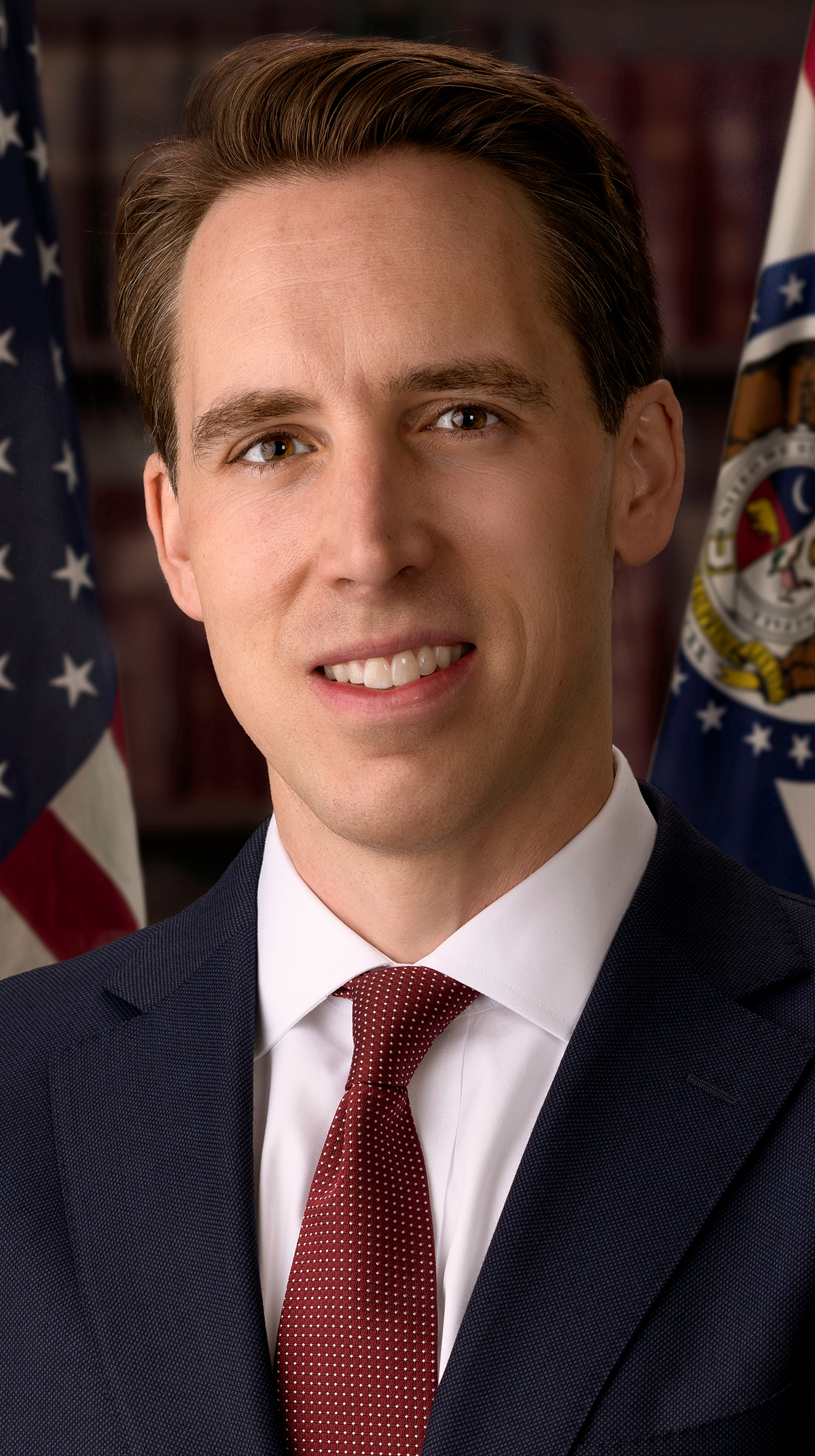

Earlier this year, in a subcommittee hearing, Republican Senator Josh Hawley called out insurance companies for their alleged fraudulent practices after natural disasters: “At the end of the day, they just won’t pay what is due. What is required. What is just.” Hawley was not coy about the motivations for such behavior, claiming, “It is a deliberate strategy to maximize profits.” Hawley represents a growing contingent of conservatives interested in what Senator Marco Rubio has called “common-good capitalism.” In 2019, Rubio gave a lecture at The Catholic University of America, drawing heavily on Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical on capital and labor, Rerum Novarum. Rubio argued, in line with the encyclical, that laissez-faire capitalism needs to be bridled by the moral obligations employers owe to employees and, more broadly, to the common good of society.

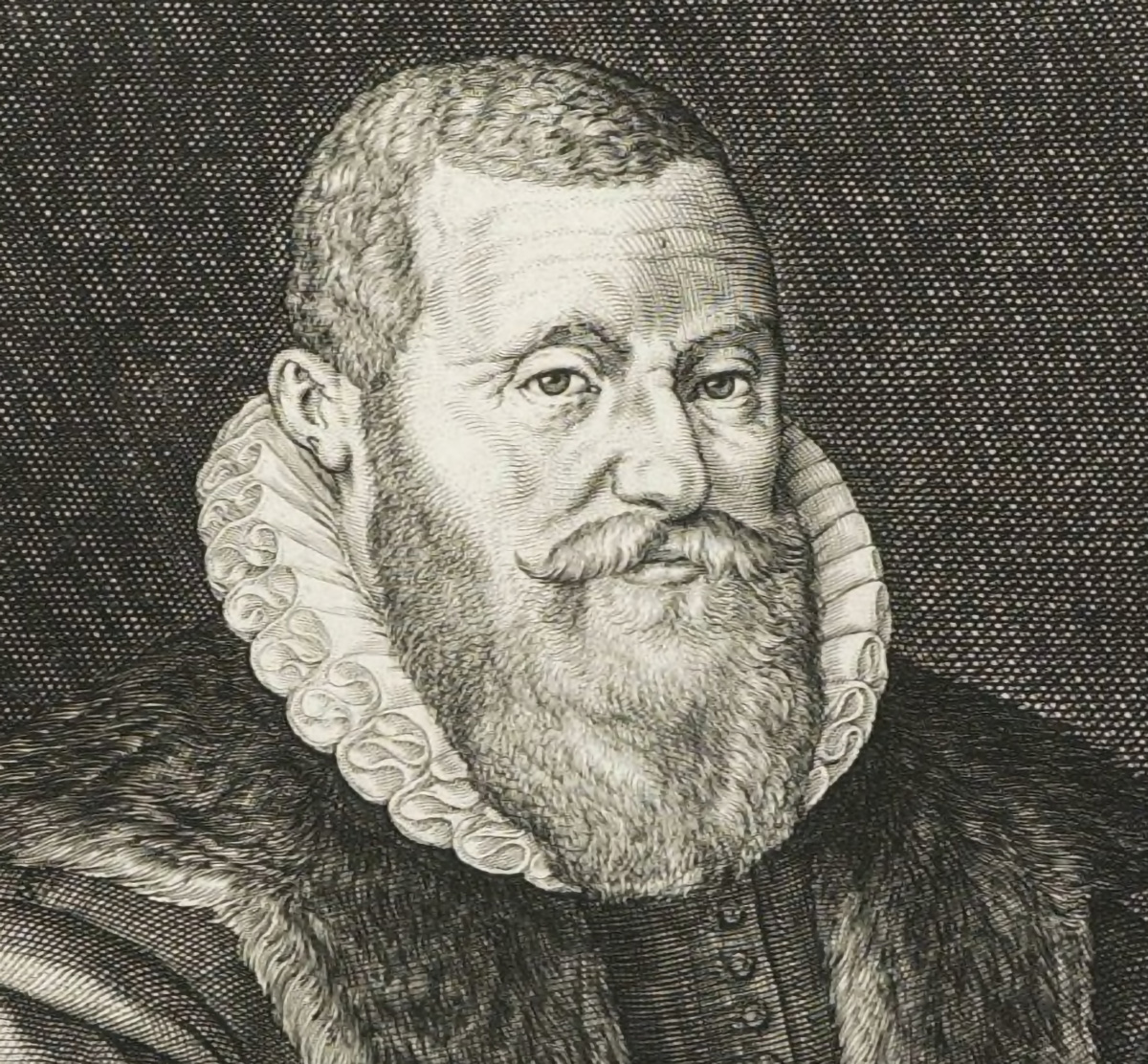

Can doing business be a way of cultivating virtue? One minister of the Dutch Golden Age thought so. He has much to teach us today.

By Daniel Souterius

(CLP Academic, 2025)

In tone and theme, the recently translated Latin treatise On the Duties of Merchants by Daniel Souterius (1571–1634) resonates with this common-good conservatism. Souterius, a relatively minor figure in early modern Protestantism, was born in England of Flemish descent and raised in a mercantile family. He studied at the University of Leiden—a bastion of Renaissance humanism—before becoming a Dutch Reformed minister. A rather prolific author, Souterius published On the Duties of Merchants in 1615, dedicating it to the directors of the Dutch East India Company, which, though founded only a decade earlier, would prove a key player in the so-called Dutch Golden Age of the 17th century. While ostensibly addressed to merchants, the fact that it was written in Latin rather than in the vernacular may suggest an additional apologetical purpose, perhaps aiming to persuade the broader European intelligentsia of commerce’s moral legitimacy.

Souterius outlines nine “duties of piety necessary in conducting business”: (1) maintain a good conscience, (2) eschew deceit, (3) pursue honesty, (4) love justice, (5) put off pride, (6) provide charity for the poor, (7) cultivate contentment, (8) avoid worry, and (9) love heavenly things. The editors of this translated edition note that the work functions simultaneously as a handbook for Christian merchants, a guide to business ethics, and a humanist defense of commerce itself. This latter purpose might sound foreign to our modern capitalistic sensibilities, but suspicion of trade has deep roots. From the Chinese philosopher Wang Fu to many early Church Fathers, foreign trade was viewed as a breeding ground for avarice, undermining local economies and civic virtue. Professions in commerce and trade have always been morally suspect. Ecclesiasticus (or Sirach) 26:29 bluntly declares: “A merchant can hardly keep from wrongdoing, nor is a tradesman innocent of sin.”

Against such pessimism, Souterius presents trade not as a necessary evil but as a divinely sanctioned means of preserving life and fostering community: “Trade preserves human life and supplies clothing and nourishment for oneself … and [for those] we hold dear and ought to protect.” In this, he echoes (Pseudo-)Plutarch: “[The sea] has rendered sociable and tolerable our existence which, without this, would have been fierce and without commerce, by making available through mutual assistance what otherwise would have been lacking, and by bringing into existence, through the exchange of goods, community and friendship.”

The title of Souterius’s work consciously evokes Cicero’s De Officiis (On Duties), and indeed, Cicero is his most frequently cited source. One striking feature, at least by modern standards, is the sheer density of quotations relative to Souterius’s own words. He likens his work to that of a bee: “Let me therefore pluck the most exquisite little flowers from the books of different writers … and offer you profitable and pleasant libations from them.” Souterius quotes such “libations” liberally from a panoply of classical pagan and Christian authors, including Cicero, Seneca, Horace, Plato, and Plutarch, but also Augustine, Lactantius, Bernard of Clairvaux, Boethius, and Ambrose. In typical Scholastic fashion, each chapter begins with a definition of the virtue or vice under consideration, followed by arguments—both theological and practical—for embracing or avoiding them.

Souterius unapologetically writes for Christian merchants—or at least those who claim to be such. While encouraging them to be generous to the poor in their midst, he quotes Colossians 3:12: “As the elect of God, holy and beloved, put on tender mercies, kindness, supporting one another.” For Souterius, the virtue of pietas (piety or godliness) is the foundation of all moral conduct, the root from which all other virtues grow. Since Dutch merchants professed to be Christians, they were obligated to do business with the full awareness that their actions unfolded under the watchful eye of divine providence. Greed, for Souterius, is not merely one vice among many but the root of all—the fountainhead of deception, fraud, stinginess, and the love of earthly things over heavenly ones.

Still, Souterius is no proto-socialist. He is careful to state that his “intention is not to take riches and other goods away from Christians altogether.” Quoting Ambrose, he assumes the maxim abusus non tollit usum (“abuse does not take away proper use”): “Guilt is not in the goods themselves, but in those who know not how to use them.” The problem is not with wealth or commerce per se but with their misuse. The just merchant sees wealth not merely as private property but as a trust for the common good.

Pliny the Younger is invoked to emphasize that care for the poor must go beyond family or civic obligations: It demands active attention to those truly unable to help themselves. Souterius appeals not only to Christian charity but also to natural law, reminding readers that “we are all made from the same lump and substance, so that every man is the same thing we are, that is, flesh.” And he is not above pragmatic arguments: Honesty ensures a good name for one’s family; justice avoids litigation; humility guards against the futility of material accumulation. As he reminds the reader, “What are all the things that accrue to us in this life except inconstancies subject to motion?”

Souterius’s call is for merchants to take personal responsibility for their commercial activities in light of their dual identity as Christians and neighbors—thus fulfilling the two greatest commandments. Unlike Rerum Novarum or contemporary appeals to common-good capitalism, Souterius does not urge civil governments to restrain the excesses of the market. That is perhaps unsurprising: On the Duties of Merchants is written not to magistrates but to businessmen themselves. Yet for all its early 17th-century particularity, the work feels strikingly contemporary. In an age when global commerce is both ubiquitous and morally contested, Souterius’s insistence on personal virtue and ethical responsibility remains deeply relevant. His vision is not one of technocratic reform, nor of centralized regulation, but of virtue formation, calling each merchant to ask not “What can I get away with?” but “How ought I to live and work?”

This English edition of On the Duties of Merchants, translated with clarity and accuracy by Albert Gootjes and helpfully introduced by Joost Hengstmengel and Henri Krop, is a welcome addition to the Acton Institute’s Early Modern Economics, Ethics, and Law series. At a time when many conservatives are rethinking the terms of capitalism, seeking a model that serves the good of one’s own nation rather than an amorphous global system, Souterius reminds us that commerce, when practiced in the fear of God and love of neighbor, can be not merely permissible but morally ennobled. His little treatise deserves a place on the shelf not as a historical curiosity but as a summons to consider economic life as an arena for the cultivation of virtue. Though aimed at Christian merchants, its insights into honesty, justice, and charity speak just as clearly to any Christian seeking to navigate the moral complexities of economic life.

In the end, Souterius offers no grand policy prescriptions—only the humble conviction that a just and humane economy begins not in legislation or technological advancement but in the conscience and actions of the merchant.