It is well established that the story of the French Revolution and the American founding is largely one of interaction and mutual influence. From Publius’ deference to Montesquieu to Jefferson’s involvement in the redaction of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, both republics have since their inception proclaimed the same ideals and stretched their roots to the same philosophical sources. However, French-American relations have also been, from the start, underscored by a malentendu, a fundamental misunderstanding whose origin goes way deeper than the occasional disagreement on this or that political matter.

Two revolutions, two very different conceptions of freedom. And the locus of that difference is anthropological: Are humans perfectible?

This misunderstanding concerns the central ideal from which the American and the French republics respectively derived their legitimacy: liberty and liberté.

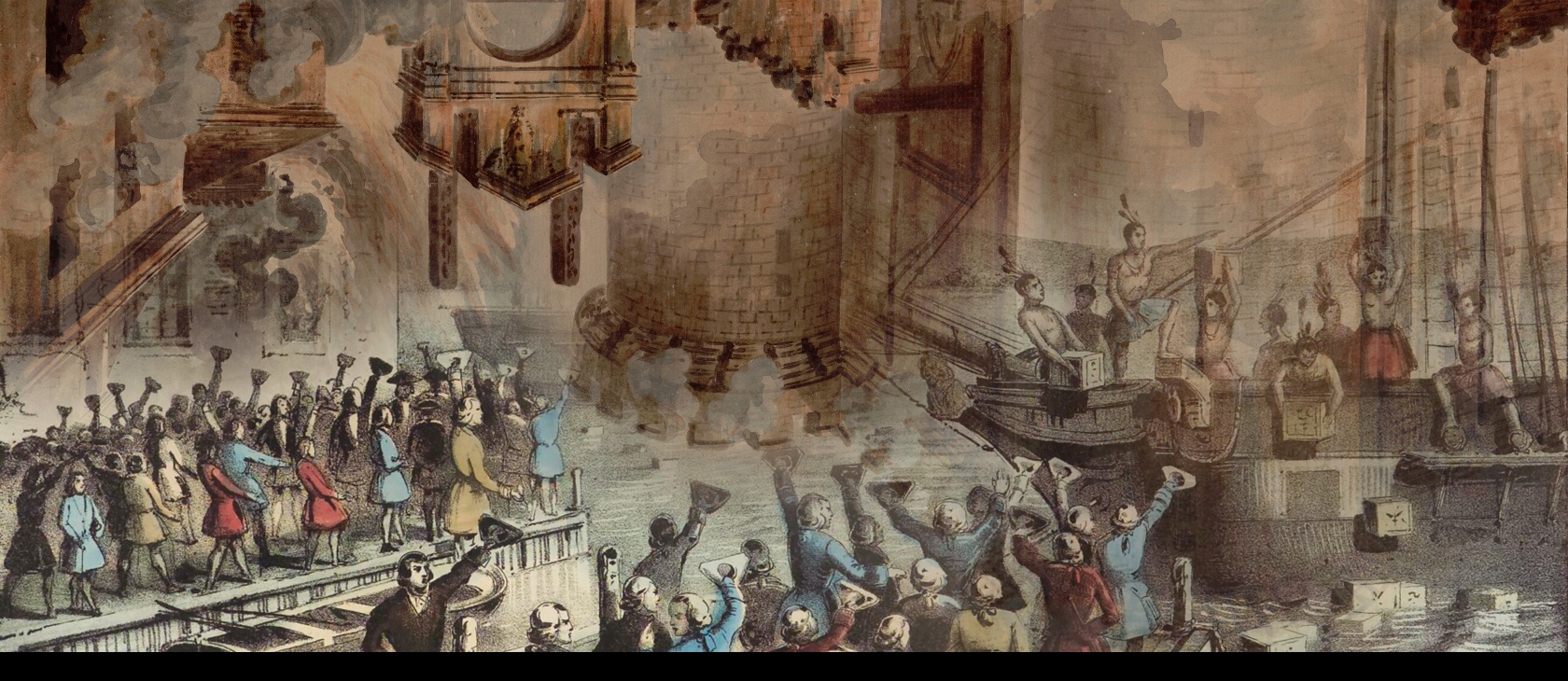

Since the people of Paris rose against the throne, early American perceptions of the French Revolution have been marked by two historical orientations that have, according to the times and circumstances, in turn found greater or lesser preeminence in the minds of the people and the political leadership. First, that the polity that was rising on the other side of the ocean was an ally and a friend in spirit and ideal. Second, that the methods used to achieve this ideal were, in appearance, so revolting that they could only be the sign of irreconcilable differences. In 1794, Alexander Hamilton observed:

In the early periods of the French Revolution, a warm zeal for its success was in this Country a sentiment truly universal. … But this unanimity of approbation has been for a considerable time decreasing. … [The American people’s] reluctance to abandon it has however been proportioned to the ardor and fondness with which they embraced it.

This malaise was famously expressed by John Adams in a letter to Benjamin Rush: “Have I not been employed in mischief all my days? … Did not the American Revolution produce the French Revolution? And did not the French Revolution produce all the calamities and desolations to the human race and the whole globe ever since?”

A couple of decades earlier, Thomas Jefferson expressed a view to his secretary that described the puzzle the French Revolution represented to the contemporary American observer:

In the struggle, which was necessary, many guilty persons fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent. … But I deplore them as I should have done had they fallen in battle. … The liberty of the whole earth was depending on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood?

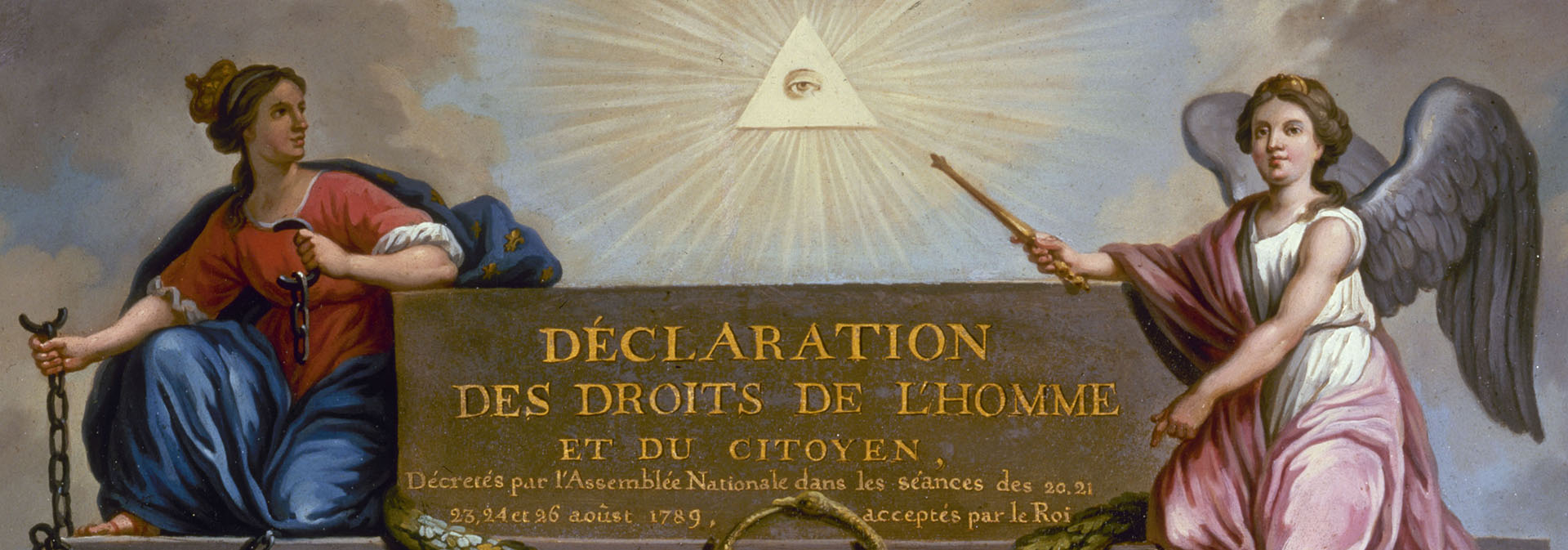

How then could this ambiguity and resulting uneasiness in appreciating the events of the French Revolution be explained? One could begin by turning to the well-studied tension between equality and liberty, with the French Revolution, it was typically believed, having put greater emphasis on the former, and the American on the latter. However, the founding acts of both republics proclaim ontological equality and natural liberty as joint pillars of the republics to come. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789 declares all men “born free and equal in rights,” and the Declaration of Independence recognizes the “self-evident truths” that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with … Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” And while several egalitarian provisions are made later in the French declaration, liberty remains by far the most emphasized of the principles of 1789.

Furthermore, as rightfully noticed by Rett R. Ludwikowski in The American Journal of Comparative Law in 1990, equality does not, unlike liberty, figure in the enumeration of sacred rights derived from the nature of mankind. Similarly, Wendell J. Brown clarifies that the idea of equality as mentioned by the Declaration of Independence derives its meaning from liberty rather than the reverse, since it is not based on the premise that men are equal in terms of their capacities, but rather of their ontological worth, which gives them an equal right to self-determination and grounds the three basic principles of the gift and right to life, equality of opportunity under just laws, and consent of the governed as the locus of government legitimacy (“Liberty and the Declaration of Independence,” 1962). In short, men are equal according to the measure of their freedom, not free in the measure of their equality.

On the other hand, while both republics recognize the preeminence of liberty over equality as a natural right, they begin to diverge from one another in the practical consequences they derive from this recognition—i.e., in their political theory of liberty. The specificity of the French understanding of liberty compared to the American one can thus be ascribed to the former’s decidedly Rousseauian character.

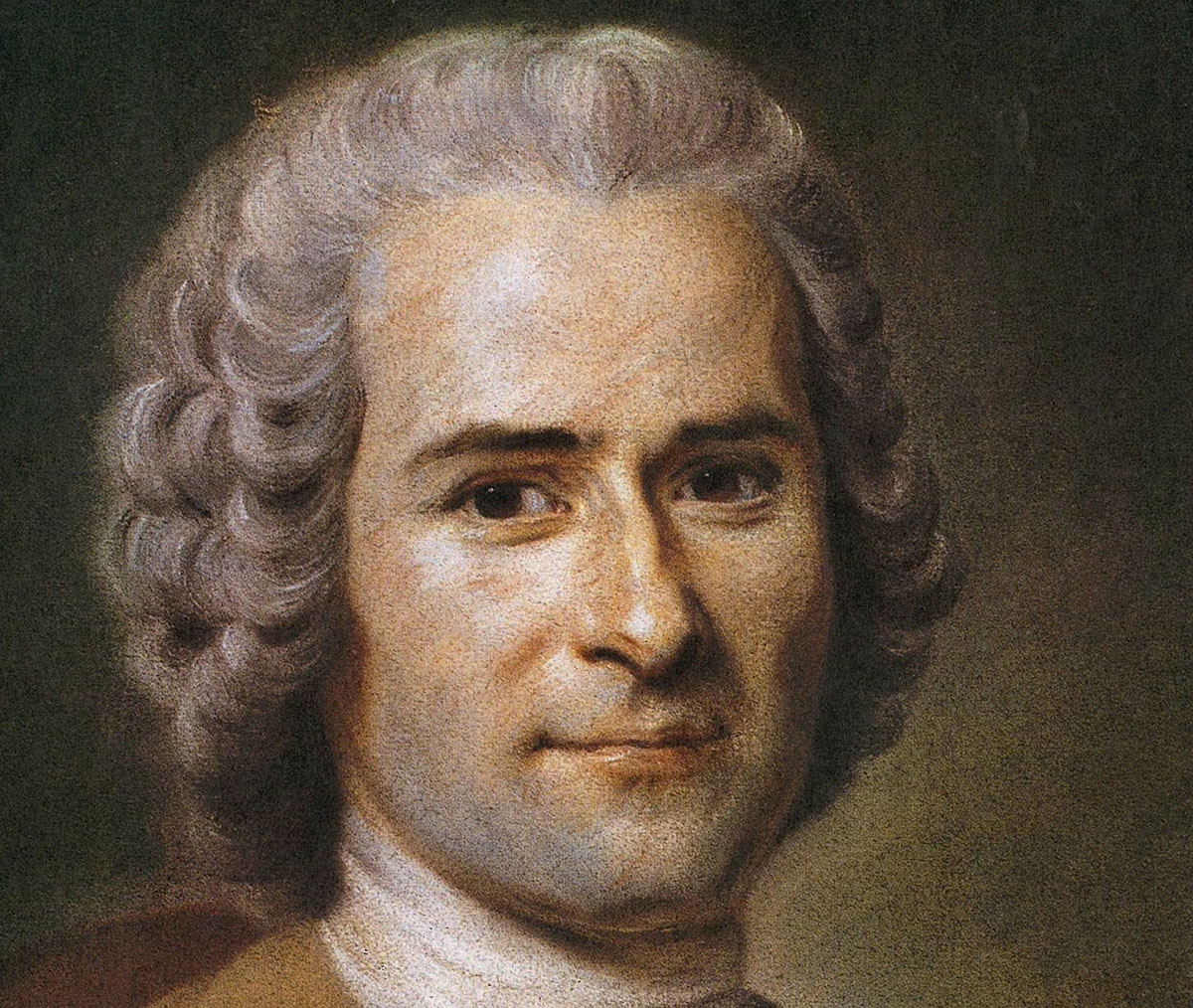

According to Richard Schottky in “La Liberté d’après Rousseau” (1964), Rousseau defines political matters as a mere aspect of the “total” problem of morality. His political theory identifies the State with morals, reason with will, and ultimately abolishes the distinction between “legality and morality.” As with every reasoning on political institutions, Rousseau’s theory begins with an anthropological premise: Evil is not naturally part of the human condition; rather, it is the result of an alienation brought on man by man himself. As such, it is not a primitive necessity but an artificial perversion that can and should be removed through political institutions. In other words, man is morally perfectible, and it is the raison d’être of political institutions to bring about this perfection through moral education, which is the prerequisite for individual autonomy.

Therefore, the foundation of real freedom is the development of political morality, brought forth by the State: It is by participating in political life that man becomes “truly” free, for it is only in and through the State that man becomes a moral being. Outside the State, man is only free in the sense of “a stupid and stubborn animal.”

Rousseau's theory begins with an anthropological premise: Evil is not naturally a part of the human condition.

The solution proposed by Rousseau to the problem of the harmony between this political-moral order and individual autonomy is a rather radical one: In The Social Contract (1762), the Savoyard identifies the individual with the community, the personal with the “general” will. Using his terminology, the Declaration of the Rights of Man declares that “law is the expression of the general will.” Rather than the mere sum of individual wills, the general will is understood by Rousseau as a synthesis of the latter, the organic manifestation of each citizen’s participation in the life of the city as part of a greater “body.” The destination of the general will is the common good, which, for Rousseau, is synonymous with common morality. Indeed, since man is essentially good and is made so again through his participation in political life, the individual’s “true” will, manifested in the general, is necessarily inherently moral. Hence, whatever goes against the general will can by construction never be equal to an individual’s “true” will but solely can be a reflection of egoistic interests that are at best residuals of the perversion being eradicated. Therefore, “in obeying the law, [citizens] only obey themselves,” and are, therefore, free. It is in this sense that Rousseau’s definition of freedom as “the obedience to [a] self-prescribed law” is to be understood, the “self” referring to the political realization of the individual in the general will.

According to Otto Vossler in a chapter dedicated to Rousseau’s thought in his book Der Nationalgedanke von Rousseau bis Ranke (1937), this “revolutionary” abolition of the conceptual boundary between sovereign and subject through the general will reduces the State to an external materialization of the individual’s desire to become a moral being—and therefore liberate—himself. The immediate consequence is the legitimization of legal constraint as an essential means for the State to accomplish its moral purpose. Constraint and punishment are thus legitimate as long as they serve the necessary suppression of immorality, which entails the preservation of the State as the expression of the general will.

Therefore, for Rousseau, there is no contradiction in affirming that “whoever should refuse to obey the general will shall be … forced to be free,” supporting a conception of freedom that, in its fullness, is essentially a political product. This conception is echoed in Robespierre’s description of the revolutionary government as “the despotism of freedom” against tyranny. In the French-Rousseauian paradigm, the measure of freedom lies not in the capacity of the particular to resist the general, but rather in the degree to which the particular is accomplished in the general. The appreciation of this dynamic is sometimes reduced, in Rousseau’s thought, to an examination of the will of the majority as a practical expedient. Robespierre again: “As long as the majority demands the preservation of the law, every individual who violates it is a rebel, were it wise or absurd, just or unjust; his duty is to remain faithful to it.”

Conversely, in the more classical understanding of natural liberty that inspired the American founding, men are born completely free and are naturally prone to both good and evil, including the temptation to encroach on the freedom of others. Since the tendency to yield to such temptation is the result of man’s constitution and not of a socially induced perversion, it is not something that can be remedied. As beautifully described by Herbert Hoover in The Challenge to Liberty (1934), quoted by Brown, the delegates to the Second Continental Congress accordingly based their actions on a common reckoning of the elements they considered constitutive of human nature:

Such evil instincts and impulses as shiftlessness, envy, hate, malice, fear, over-pugnacity and will to destruction; selfish instincts and instincts of self-preservation, acquisitiveness. Curiosity, rivalry, ambition, desire for self-expression, for adulation, for power ... the altruistic instincts of courage, love, and fealty to family, and to country, of pity, of kindness and generosity; of love of liberty and of justice; the desire to work and contract, for expression of creative faculties; the impulse to serve the community and nation; and with these also hope, faith, and the mystical yearnings for spiritual things.

This premise provides the basis for an approach to political theory anchored in observable data rather than a priori speculation, and logically leads to the conclusion that any sustainable political system must integrate within itself man’s flawed nature rather than attempt to perfect it. It is precisely this approach that Jefferson and Adams, despite their disagreements and divergences regarding the specifics of implementation, shared and employed in devising the philosophical foundations of the American system of government. In his notes on Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality (1755), Adams accordingly criticized the latter’s method by writing that:

Reasonings from a State of Nature are fallacious, because hypothetical. We have not facts. Experiments are wanting. Reasonings from Savage Life are not much better. Every Writer affirms what he pleases. We have not facts to be depended on.

Interestingly, this fact-based approach is partly defended by Adams in these same notes as a way to oppose the weakening of the “Reverence to the Christian religion” in political theory induced by the use of concepts such as the state of nature, the “savage life,” and what he calls “Chinese happiness.” Likewise, in his Summary View of the Rights of British America(1774), Thomas Jefferson found it proper to reaffirm the divine origin of liberty by declaring that “the God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time,” prefiguring the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence.

It is with respect to the observable characteristics of human nature and the decrees of heaven that the State is to play the role of protector of individual freedom, which comes from above it and finds precedence over it. Its function with regard to freedom is at best that of a guardian but not of a catalyst. Therefore, the State’s action must stop where the prerogatives of the individual begin.

In short, morals and politics, despite some degree of permeability, are not identical, and the former has preeminence over the latter. The more the State gains ground, the less individuality finds the space necessary for its liberty to unfold. Freedom, for the American revolutionaries, was strictly the limit of political authority, and its natural completeness did not necessitate its actualization through political intervention.

This conception is made most apparent in its practical implications, particularly when coming to terms with the problem of the diversity of interests. For example, Madison’s famous Federalist Paper on factions, while acknowledging the danger these may pose to the viability of institutions and the advancement of the general interest, recognizes them as an unavoidable fact, naturally following from “the diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate.” Therefore, any attempt to repress this natural diversity by force would necessarily imply tampering with property rights and ultimately undermine human liberty, whose protection Madison recognizes as “the first object of government.” The solution, rather, was to let factions multiply freely to minimize the probability that one could impose its interests on the others. This is obviously at odds with the ideas of human perfectibility and of constrained liberation of the individual by the majority contained in Rousseau’s political thought, which in a classical American perspective is an impossibility.

Therefore, when Adams describes liberty as “a self-determining power in an intellectual agent,” he restricts the process of self-determination to the individual himself according to the limitative theory of political authority to which he subscribes, as a deliberation within the former’s own conscience and interiority. And while Rousseau’s definition of freedom as “obedience to a self-prescribed law” can appear similar at first glance, the conceptual identification of subject and sovereign contained in the idea of general will admits an externalization of the process of self-prescription to the level of the communal body, subsequently transcending the individual.

This influence of Rousseau on the French revolutionaries and the beginnings of the Revolution did not go unnoticed by many American observers, chief of whom was John Adams. Indeed, his mostly virulent and already mentioned criticism of Discourse on Inequality, written 34 years before the fall of the Bastille to the people of Paris, could in part be explained by the fact that he wrote it in 1794, at the height of what would later be known as the Terror. When he composed his famous “I know not what to make of a republic of thirty million atheists ” in a letter to Dr. Price on April 19, 1790, Adams had already mentioned Rousseau as one of the “encyclopedists and economists,” along with Diderot, Voltaire, and d’Alembert, whom he insisted had contributed more to this “great event … than Sidney, Locke, or Hoadley, perhaps more,” he added, “than the American Revolution.”

The state's function with regard to freedom is at best that of a guardian but not of a catalyst.

However, while it is true that Rousseau himself admits at times the possibility of majority rule as a practical expedient for the general will—which as we have seen cannot quite be reduced to the former on a conceptual level—his political theory, whatever its limits, was still initially devised as an antidote to tyranny and should in no way be understood as offering a justification for it in the sense of an authoritarian and unjust government. Rousseau’s political theory of liberty shares with that of the Founding Fathers the absolute necessity of morality as a condition for a functioning social and political life. This concern is made evident in the duty of the State to ensure and advance moral education, as well as in the conception of civic freedom as entailing the individual’s moral development.

Nevertheless, by describing the French Revolution as one where “privilege was more detested than tyranny,” in his essay “Nationality” (1862), Lord Acton, for one, seems to imply that the French revolutionaries were ready to accept the latter if they would have thereby gotten rid of the former, which hardly fits Robespierre’s description of the revolutionary government as the “despotism of freedom” over tyranny. However, just as a justification for tyranny, in the sense of an authoritarian and unjust government, is not found in Rousseau’s theory, neither was its possibility admitted in the minds of the French revolutionaries: They sincerely believed in the possibility and the necessity of moral despotism. Despotism was thus seen as a necessary but insufficient condition for tyranny, which required the unjust wielding of political authority; contrary to the American liberal tradition, which considered despotism as a sufficient condition for tyrannical government in itself.

Indeed, from the American perspective, despotism necessarily implies the abolition of the limits imposed on political authority by divinely granted freedom and is therefore in itself inherently unjust. The upholding of this conception, however, presupposes that the distinction between individual and general, subject and sovereign, is preserved, which, as we have seen, is not the case in the Rousseauian paradigm, which relies on and vindicates the possibility of constrained liberation for moral purposes.

While an explication of the distinctives of liberty and liberté can go a long way in explaining centuries of uneasy cooperation between France and the United States, the main point is that liberty remains a word of few interpretations but many meanings. In the 1840s, Levi Preston, a veteran of the Battle of Concord, is said to have been asked by a young historian, Mellon Chamberlain, whether he and his comrades had been influenced by figures such as James Harrington and John Locke in their struggle for freedom, to which Preston nonchalantly answered, “I never heard of ’em. We only read the Bible, the Catechism, Watt’s Psalms and Hymns, and the Almanack.”