Europe was changing rapidly in the 16th century. The advance of humanism and the Protestant Reformation offered challenges to the Church’s authority and the very idea of what it meant to be both a Christian and a human being made in the image of God. Meanwhile, the Spanish Empire was expanding, and the complexity of its administration grew along with the military and bureaucratic power of the kingdom. For years, the arrival of gold and silver from the Americas created a vast economic resource that enabled an increased growth in government without adding new taxes or indebtedness. As expenses grew and imports declined, however, the kingdom began to face significant economic challenges and mounting financial commitments.

Emerging in the 16th century, the School of Salamanca was a revolutionary intellectual movement that transformed thinking in economics, international law, and philosophy. It still has much to offer.

An empire as important as Spain’s had, of course, developed an impressive education system. Universities flourished, and chief among them was the University of Salamanca. Founded in 1218, it attracted academics from all over Europe and became a center for intellectual investigation. Its greatest strength was dealing with the moral, legal, and financial consequences of the fiscal and inflationary pressures facing a truly global empire.

Among the concerns of the Salamanca academics were the ethical aspects of economic activity, which had long been in thrall to certain theological constraints and the legal systems controlling world relations. What resulted was the “Salamanca school,” which would produce an impressive body of work that would go on to influence policymakers and economists for centuries.

The Salamanca school was unique in its intellectual advancement because it created the foundations of classic liberal thought and did so from a moral perspective within the broader teachings of the Catholic Church. Its main achievements included the development of exceptional and groundbreaking contributions to economic theory, particularly in the areas of value, money, and international trade.

Often regarded as the founder of the school, Francisco de Vitoria (1483–1546), a jurist and theologian, is hailed as the framer of modern international law. He promoted the rights of Native American peoples and first broached the idea of natural law as a foundation for world politics. The School of Salamanca, and Vitoria’s works in particular, fostered truly “universal” human rights as we know them today, arguing that these were inherent and thus not dependent on political or religious affiliations. What we regard as normative—basic human rights—was a revolutionary concept at the time!

Following the same principles of natural law, which fit perfectly with the doctrinal development of the Catholic Church, theologian and lawyer Domingo de Soto (1494–1560) further developed the wedding of law and morality, condemning repressive legislations infringing basic rights. De Soto’s contributions to modern economics included the idea of a “just price” determined by market forces rather than by divine or government will. He also investigated the monetary factors behind inflation.

The School of Salamanca was innovative not only in its work defining human rights, morality of law, and justice. Its exceptional analysis of monetary factors and inflation from a moral and public administration perspective is also exceptional. The seminal work of Martín de Azpilcueta (1491–1586) was the foundation of what we know today as sound money. Azpilcueta was, in fact, responsible for the earliest version of the quantity theory of money. His research on the link between money supply and inflation was revolutionary. In a similar way, Juan de Mariana (1536–1624) analyzed the negative impact of government interventionism on the economy. In addition to his essential work on tyranny and interventionism, we must highlight Mariana’s writings on currency debasement as the cause of inflation and financial instability. His essay De Monetae Mutatione (1609) emphasized the need for sound money and highlighted the risks of inflationary measures, establishing the groundwork for contemporary monetary theory.

The School of Salamanca, and Francisco de Vitoria's works in particular, fostered truly 'universal' human rights as we know them today.

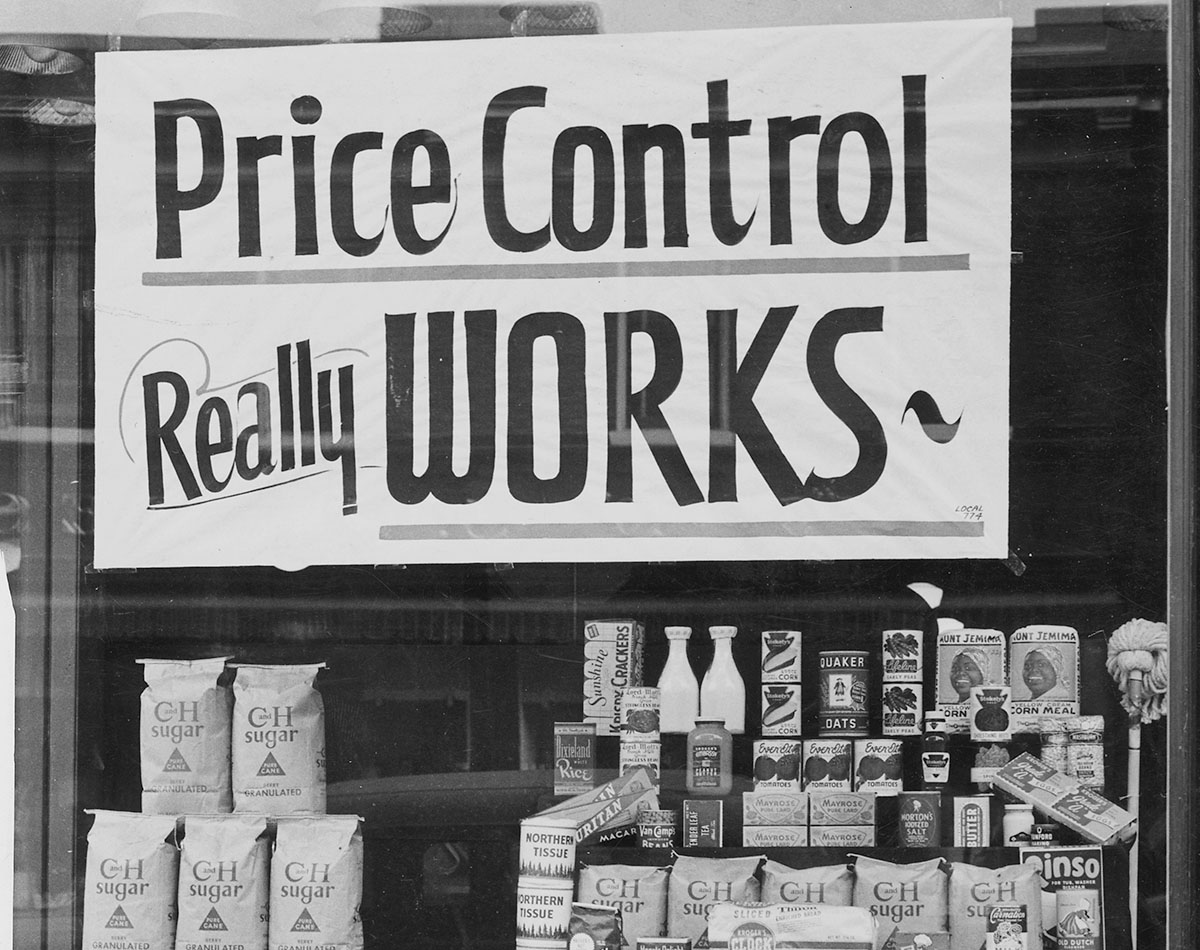

One of the most intriguing defining elements of the Salamanca school was how incredibly anti-mainstream and anti-consensus it was for the time. There was a general perception that laws were fair and just simply because the king enforced them, that prices were decided by untrustworthy speculators and external conspirators, and that religion, race, and class should dictate the rights of individuals. Yet today we understand as a matter of course that misguided monetary policy is the main cause of inflation, that price controls achieve the opposite of what they intend, and that the role of government is as a defender of human rights and individual liberty.

In fact, when we examine the challenges of the world economy today, the teachings of the School of Salamanca prove to be exceedingly valuable.

Government spending and monetary expansion have become the key drivers of economic policy, and we’re witnessing a concerning rise in protectionist and interventionist measures. Governments and central banks have become lenders of first resort, and global public debt reaches record levels almost every year, driven by a continuous increase in public sector liabilities. Gradual reduction of individual liberties, threats to private property, and persistent inflation have also become significant concerns that affect most developed economies.

The teachings of the School of Salamanca remind us of the dangers of allowing government to become too large and of debasing the currency to disguise rising fiscal imbalances. Modern governments increasingly resort to higher taxes, more debt, and monetary easing (artificially lowering interest rates or increasing the money supply) to pay for entitlements and subsidies. Spain took similar measures, issuing currency without backing or control and resorting to political intervention, repression, and protectionist measures.

Spain also made all manner of political excuses to justify inflation. Though the empire took pride in having established sophisticated economic and political administration systems, it nevertheless asserted that traders, malicious foreign nations, and various businesses were conspiring to drive up prices. We have learned little from this poor example. In recent years, we have heard politicians blame “greedy corporations” for inflation, with some neo-Keynesian economists like Isabella Weber coining words such as “greedflation” to supposedly explain the phenomenon.

Moreover, Spain, which had built a strong and thriving private sector and a potent middle class, became protectionist when threatened by international commerce (sound familiar?). The king implemented trade barriers and taxes on imports to avoid competition in the sectors he favored while at the same time he encouraged trade agreements.

Salamanca reminds us that the moral principles of Catholic doctrine and the teachings of the Bible are completely compatible with the notions of free markets, individual liberty, and small government.

In essence the empire was on one hand protectionist for “strategic” sectors, but on the other it needed open trade for others. We see something similar in regard to China, the U.S., and the EU today.

Thankfully, classic liberals and students of the Austrian School of Economics were inspired by Salamanca and developed instead the understanding of the monetary factors behind inflationary pressures. From Claudio Borio to Tim Congdon, Steve Hanke and Joseph Salerno, we have plenty of scholarly empirical analyses that prove the link between rising government spending and money supply growth and inflation. These modern studies are clearly inspired by the early research of the School of Salamanca.

The School of Salamanca was key to the development of our understanding of the importance of human action and freedom as basic principles of prosperity and growth, but also the moral superiority of free trade, private property rights, and economic freedom. Salamanca also reminds us that the moral principles of Catholic doctrine and the teachings of the Bible are completely compatible with the notions of free markets, individual liberty, and small government. (For further reading on that score, consider The Economics of the Parables by Fr. Robert Sirico.)

As an example of the ongoing relevance of the Salamanca school, Joseph A. Schumpeter’s History of Economic Analysisalludes to both Spanish Scholastic and the Salamanca school of economic thought. Furthermore, Friedrich von Hayek also recognized the contribution of the School of Salamanca. In a letter written in 1979, he cites positively libertarian thinker Murray Rothbard’s essay “New Light on the Prehistory of the Austrian School,” wherein we read that “the theoretical principles of the market economy and the basic elements of economic liberalism were not designed, as we believe, by Calvinists and cautious Protestants but by the Jesuits and members of the School of Salamanca during the Spanish Golden Age.”

A key lesson to be learned from the School of Salamanca is the morality of power. Excessive power in the hands of government, added to monetary and legal repression, are seeds not only of a faulty economy but also of corruption. Juan de Mariana’s words about tyranny resonate today. He noted that the tyrant appropriates the goods of individuals because he always expects them to be possessed, as he is, by the vices of avarice, cruelty, and fraud, thereby justifying his expropriation. In Rothbard’s words, Mariana might be called “the forebear of John Locke’s theory of popular consent and the continuing superiority of the people to the government.” As for tyrants, Mariana insisted that they try to injure and ruin everybody, but they direct their attack especially against rich and upright men throughout the realm. “They consider the good more suspect than the evil; and the virtue which they themselves lack is most formidable to them. … They expel the better men from the commonwealth on the principle that whatever is exalted in the kingdom should be laid low.”

We cannot ignore how relevant these teachings are in a world in which many states’ bureaucrats seem to consider job creators and individuals as cash machines to collect taxes even as they demonize them as a danger to society (and therefore open to all manner of name-calling and even violence). This is critical because one of the things we see today in debates on economics and politics is precisely the advent of tyranny presented as the savior from an onerous and aggressive external enemy, as well as a constant attack on those who are productive yet deemed insufficiently “progressive.”

By studying the Salamanca theorists, we can obtain a better understanding of how the recent rise of interventionism and protectionism result only in the diminution of purchasing power and a transfer of wealth from individuals to the government. The Salamanca scholars understood that every measure implemented by the kingdom to prevent free trade was generating an equally aggressive and negative impact on progress and the welfare of the poorest. Scarcity of goods worsened, and prices soared as competition declined, and only the wealthy few could access the more expensive essential goods and services.

As persistent inflation became a challenge in the years 2021–24, many politicians and some economists, like Stephanie Kelton, defended government price controls. If only they had read de Vitoria, who was particularly clear about such interventions! When goods are plentiful, there is no need for a maximum set price; when they are not, price controls do more harm than good. He also argued that price increases in his own day were not the result of traders colluding in different economic sectors but poor monetary policy.

Luis de Molina also contributed to a better understanding of pricing mechanisms. He asserted that the value of goods does not depend on their importance. For example, it was perceived as evil to raise the price of something as essential as medicine. Molina explained that it was the opposite: that the pricing of goods and services must be done according to the ability to serve human utility: “We can conclude that the just price for a pearl depends on the fact that some men wanted to grant it value as an object of decoration.” In other words, individuals determine the valuation. Thus, he understood the crucial importance of free-floating prices and the relationship to enterprise: For government to set a higher or lower price is immoral and unjust because, again, they have the opposite effect of what is intended (presumably to make goods more available to more people). Instead, price controls by government increase scarcity, raising prices.

Price controls must be understood not as a tool to combat inflation but rather as a policy to try to convince citizens that the government is in control of the economy. There is, however, only one cause of aggregate price increases: increasing quantities of money in circulation, which reduces purchasing power. Governments need to make citizens believe that inflation is caused by anything but the reduction of the purchasing power of the currency. Yet only a constant destruction of the currency value through currency expansion creates inflation and makes prices rise. This was exceedingly difficult to understand in the 16th century because many people believed that generating larger quantities of money and producing more currency was not just a way to support the vast bureaucracy and administration of the empire but also a very important social policy. Unfortunately, these false ideas have not disappeared, and the defenders of modern monetary theory continue to argue for increasing the money supply as a solution to unemployment and slow economic growth.

Moreover, the idea that more currency in circulation will generate wealth by increasing trade and solidifying an economy’s global position is obviously incorrect, as it forgets that the state of the currency represents the creditworthiness of the issuer, and that inflation reflects a loss of confidence in the credit of the nation. The importance of having confidence in one’s currency is key to the Salamanca scholars’ understanding of money and morality. They argued that currency is the utmost element of what is moral, positive, and defendable about a government. A strong currency is a sign of a virtuous government, and a weak currency is the evidence of a corrupt and irresponsible administration.

In a time like today, when market participants demand constant manipulations of interest rates and the quantity of money from central banks in order to increase lending, which in turn creates an incentive for bad investing strategies, the teachings of Mariana on monetary issues also prove to be highly relevant: “I would like to give princes one last piece of advice: if you want your state to be a healthy one, do not touch the primary foundations of commerce—units of weight, measurement, and the coinage.”

The Salamanca scholars also highlighted the importance of interest rates, not as a measure of greed but as a measure of risk. In his writings, Azpilcueta asserted that “the lender may licitly demand something beyond the principal, because he loses the chance to profit from that money in some other way.” Any loan involving capital investment necessitates an interest rate to differentiate it from other loans that are either less risky or less vital for society.

Interest rates serve as a moral guideline to determine the most effective way to use capital, making it worthwhile for lenders to take risk and lend to those who will return it safely, quickly, and productively, thus making the virtuous credit cycle the most effective way to get capital to work. At the time, it was common to think that charging interest was immoral, and that speculators, bankers, and the financial sector in general existed only to exploit the most productive sectors of society. Scholars from the School of Salamanca took the counterintuitive position that charging interest played a crucial role in enhancing opportunities for business, traders, and ultimately the growth of the most productive sectors.

If we take away anything from the School of Salamanca, it is that a massive flood of money into an economy and the transferring of wealth from the productive sector to those close to government or to government itself were reflections of an immoral process: government as tyranny. we take away anything from the School of Salamanca, it is that a massive flood of money into an economy and the transferring of wealth from the productive sector to those close to government or to government itself were reflections of an immoral process: government as tyranny.

Martín de Azpilcueta asserted that any loan involving capital investment necessitates an interest rate.

Thus, their work has attracted a growing number of followers, given how so many of the same practices are having deleterious effects globally. The Salamanca influence remains to this day and informs the classical liberal, Austrian school, and libertarian communities, which continue to carry their torch.

But Salamanca’s teachings are more than just adaptable to the modern era. They also offer an essential framework for thinking about how economic systems can be designed to promote justice, liberty, and fairness. Their emphasis on the moral dimensions of economic activity and free markets encourages economists and policymakers to consider the ethical implications of government and monetary authority decisions, ensuring that economic growth is accompanied by social responsibility.

The Salamanca school’s teachings remind us of the moral characteristics of private property, free trade, sound money, and justice, and how they are intrinsically united with Catholic social teaching. Today, as a grasping for raw power seems more important than sound economic thinking, this emphasis on virtue is more important than ever.