“Love of men cannot be bought by cash-payment;

and without love men cannot endure to be together.”

—Thomas Carlyle

The harsh fluorescent lights bore down on the tops of our heads as we quietly whispered prayers and listened for any sign that she was trying to communicate to us. The oxygen and heart rate monitors were following their unpredictable course of urgent beeps, chased by the shuffling feet of nurses as they came in to assess her condition. To make sure she was still breathing. That her lungs had not collapsed.

When did “Do no harm” become outdated? When we lost the body-soul connection of patients.

For two weeks my mom, sister, and I spent untold hours at UNC Chapel Hill’s hospital caring for my sweet aunt. My mom’s older sister was a woman acquainted with grief, having buried two stillborn children and a husband at an early age, leaving their two remaining children—both of whom she had adopted after it became clear that having biological children would be too risky—fatherless and her a young widow. During most of her working years, she was a hospice nurse, a job that weathered her hands and deepened the lines on her face, but only seemed to make her generous and loving spirit even more beautiful with every passing year.

When not tending to patients or her daughters, she devoted her time to art and caring for her family and friends. She lived on the mission field for several years after coming to faith at a Billy Graham crusade back in the late ’70s. She was a painter and an artisan, molding and painting the tiniest of ceramics and sewing quilts and stuffed animals for her loved ones. She was the embodiment of Christian charity, of neighbor love.

Our family’s hospital experience during my aunt’s final days mirrors the story of millions of Americans who have held the hand of their loved ones in their final moments, contending with IVs and leads, grasping at the precious real estate of their skin, offering physical comfort through touch, even when it felt wholly inadequate as death loomed insistently in the background. Bound to the hospital bed, with the echoes of machines and unfamiliar voices bouncing off the thin walls between rooms in a crowded ward, it is the sterile death afforded many in the industrialized world, as the last light the patient’s earthly eyes behold is the cold glare of fluorescents protruding from the fiberglass ceiling tiles.

Even if your visit to the hospital is far less existential and you walk out with nothing more than 800 milligrams of ibuprofen, it is not a warm place, and your chances of being assigned a nurse or doctor with a congenial bedside manner feel too close to Vegas odds. And if you were unlucky enough to be hospitalized during the height of COVID restrictions, you were forced to suffer and, in far too many cases, die alone.

We have come to accept these standards of modern healthcare as if they were merely necessary evils in a world riddled with pain and death. But have we set our expectations too low? What if healthcare can be different? Can we recover the ethic of neighbor love that was integral to early Christians’ approach to caring for the sick? Is there room for virtue? These are questions worthy of consideration, and not just by physicians and nurses. Each of us has some stake in reclaiming healthcare, a prevailing interest in returning patients to their rightful place.

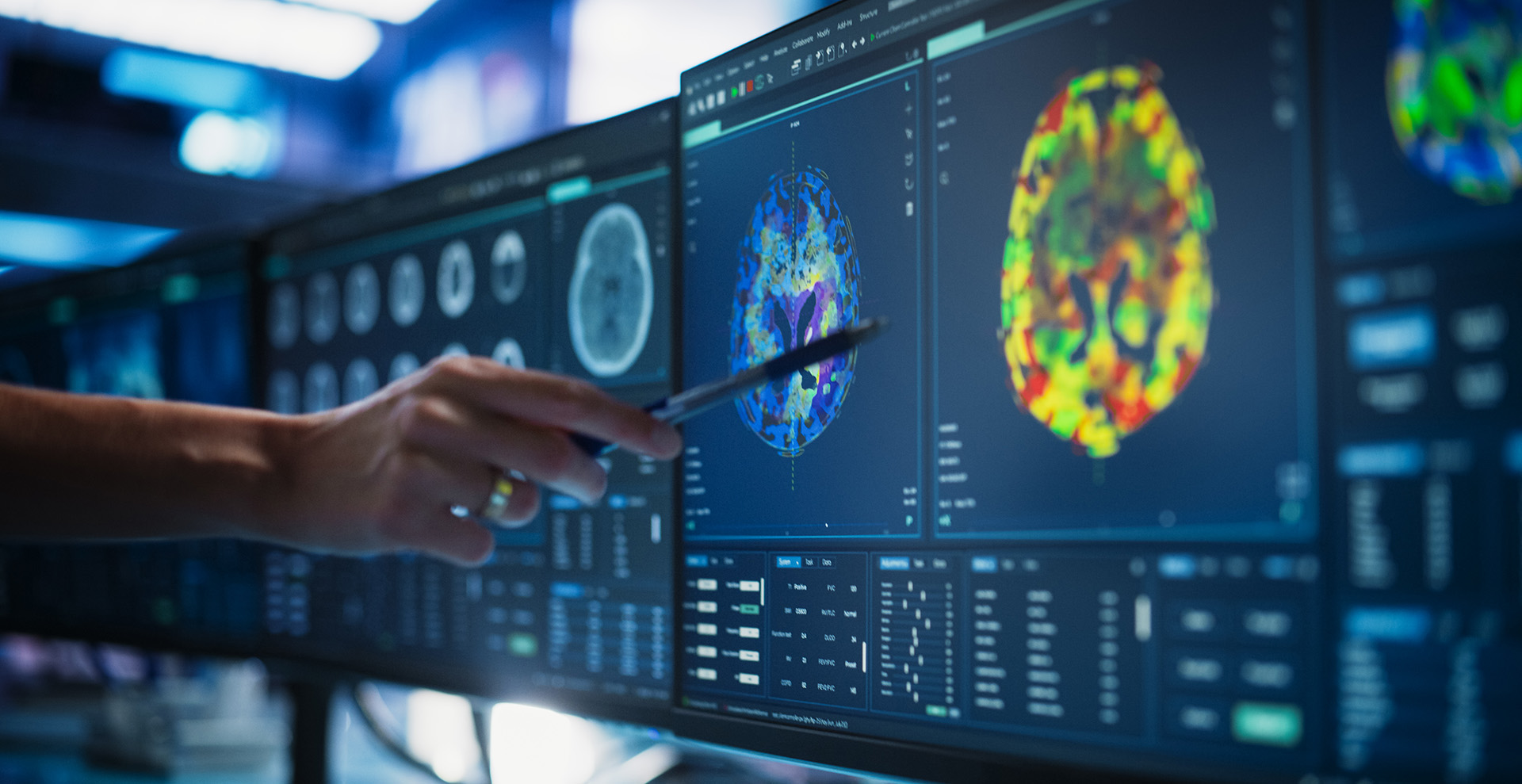

Gratefully, despite the feelings of dread and fear that often accompany the modern hospital visit, most result in healing, improvement, or diagnosis so that treatment can begin. To say we have made nothing short of miraculous strides in what medicine is able to treat is an understatement. Antibiotics and vaccines continue to save lives. MRIs and ultrasounds alert us to problems so that lifesaving interventions can be taken. Surgeries and medications improve and prolong quality of life. So why does medicine in the 21st century feel so hollowed out?

For millennia, Christians in particular have been at the forefront of medical care. Rooted in a concept of neighbor love, care for the embodied soul has been one of the vehicles Christians have worked through to communicate value and dignity to God’s greatest creation: man.

Paul Ramsey, considered a bedrock voice in medical ethics, laid the foundation for how later ethicists have understood and grappled with the moral contours of medicine and care. Opening a series of lectures in 1969, Ramsey introduced topics such as defining death in the medical sense, how to care for the dying, giving and taking organs, and consent in medical experimentation. He began digging the well from which future bioethicists would draw.

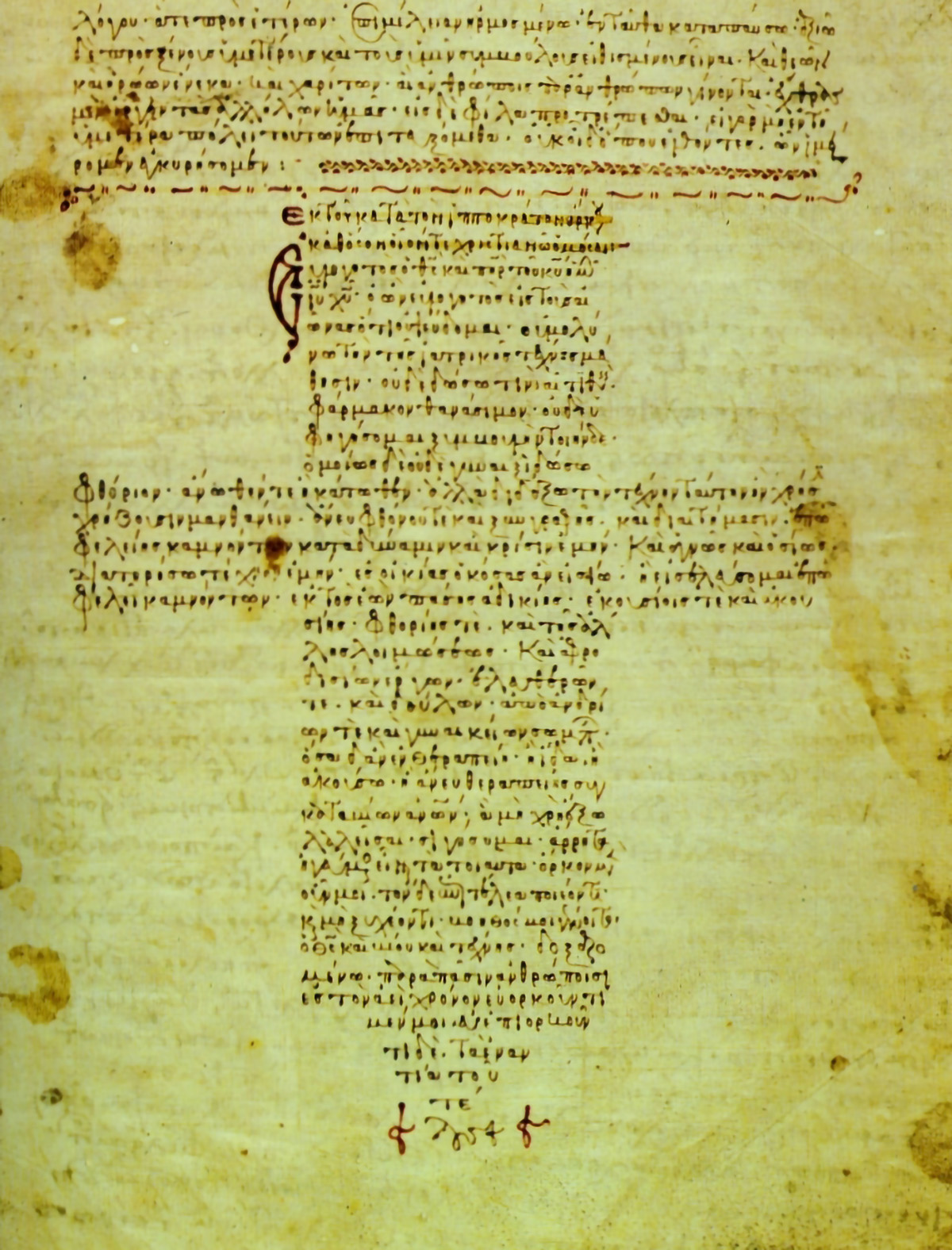

In one of his earliest lectures, Ramsey explored the historic understanding of Christian covenant in the physician and patient relationship, stating that those studying the ethics of care should “ask the meaning of the sanctity of life, to articulate the requirements of steadfast faithfulness to a fellow man.” Although Christians and physicians have been grappling with this question since their introduction to the Hippocratic Oath, which was penned in the 5th century BC, somewhere along the way medicine became untethered from its anchor of viewing man as an embodied soul. We divorced body care from soul care.

What happened?

Today the modern healthcare experience in America is fraught with anxiety, awful side effects, burdensome debt, and hidden costs that leave the patient—who should be at the center of the system—feeling like nothing more than a serf beholden to the mercurial whims of the feudal lord, their healthcare insurer. The policies governing this fiefdom are capricious and labyrinthine, often forcing the individual, who is already battling an ailment within their body, to engage in yet another fight.

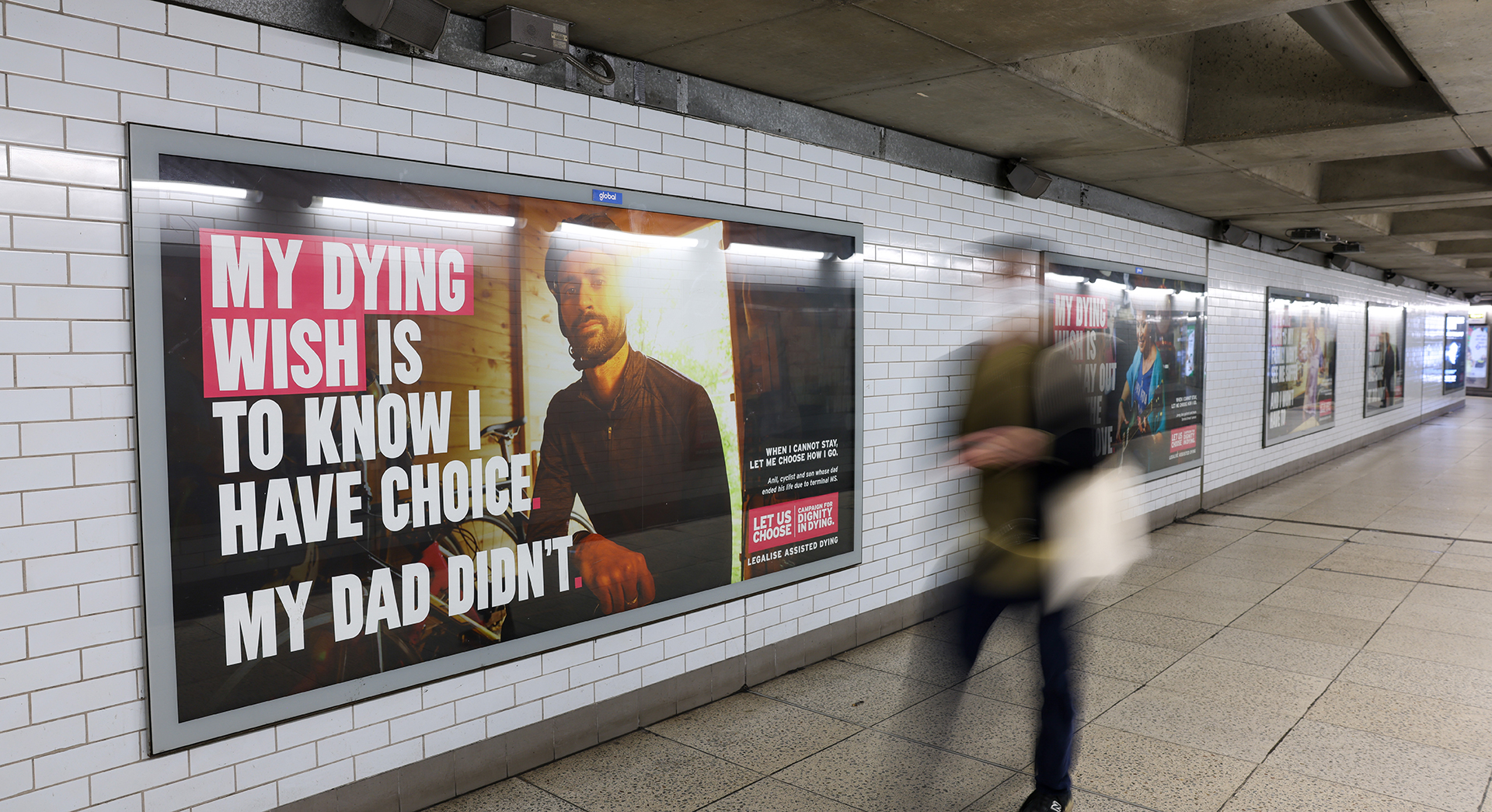

To add insult to injury, the state of healthcare has become so dire and devoid of virtuous constraints that countries like Canada, the Netherlands, and Belgium, even parts of the United States, have hollowed out the medical profession’s code of ethics to allow for assisted suicide. The latest reports from Canada reveal that assisted suicide accounts for 1 in every20 deaths of its citizens. In 2023, Canada’s government removed a number of restrictions surrounding assisted suicide, making their Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) program more widely available, to include those who are battling mental illness—even if no life-altering physical diagnosis is present—and in some cases even to minors.

Virtue formation that instructs how every individual should be treated with utmost care and dignity has been traded for DEI.

This is to say nothing of the bastardization of medicine reduced to “affirming gender care,” which has butchered children and adolescents; the full extent of this abuse likely won’t be known for years. Yet what we do know is that the majority of children who have battled gender dysphoria grow out of it, and the heightened levels of suicide rates among adolescents and adults who transition is significantly higher. The data have proven what many of us knew all along: “Healthcare” has been co-opted by idealogues whose agendas having nothing to do with upholding the Hippocratic tenet to “do no harm.”

Yet ideological progressive commitments have shut down any reasonable examination of policies related to such surgeries, not to mention permitting men in women’s locker rooms, with biological males being allowed to compete against females in women’s athletics regardless of the physical risks to the latter. The censorship on this score has been grotesque, with attempts to “cancel” anyone who refused to virtue signal support for brutalizing the bodies of adolescents walking through dark mental health battles.

Unfortunately, much of modern medicine has stripped the soul from its vocation of caring for the sick, making “men without chests.” We have expected the healthcare industry to behave virtuously, yet the foundational institutions that have served as the conscience of medicine have become severely anemic. Virtue formation that instructs how every individual should be treated with the utmost care and dignity has been traded for DEI and unconscious-bias training sessions.

But this is not a strictly 21st-century problem. The road toward this medical-ethics morass has been paved by increasing societal moral lethargy that has been slowly advancing over the past two centuries.

No one has captured the theory behind this cultural decadence quite like Pitirim Sorokin, 20th-century philosopher and professor. On the tails of the Russian Revolution, in possession of death sentences from both the Tsarists and the Bolsheviks, Sorokin left his homeland, spending the remainder of his days settling into a new life in the United States. Sorokin was eventually invited to Harvard University to establish its sociology department. One of Sorokin’s most thought-provoking contributions to this fledgling field is the classification of cultural “supersystems,” which he believed established the contours of civilization over the millennia. He believed they could be broken down into three cycles: ideational, sensate, and idealistic. These three supersystems can each be described this way:

- Ideational: A commitment to spiritual, religious, and transcendental truths. Reality is seen as rooted in the divine or the absolute. Art, philosophy, and social life emphasize faith, asceticism, and moral absolutes. Examples: Medieval Europe and the Byzantine Empire.

- Sensate: Prioritizes material, empirical, and sensory experiences. Reality is what can be seen, touched, and measured. Societies value science, technology, physical comfort, and worldly pleasures. Examples: Roman Empire and modern Western civilization.

- Idealistic: A balanced synthesis of ideational and sensate elements, seeking harmony between spiritual and material values, recognizing both the importance of transcendence and empirical reality. Examples: Classical Greece and the European Renaissance.

Sorokin believed that each of these supercultures, which generally lasts for hundreds of years, dominates and shapes every sphere of society, from ethics to art, medicine and law. His claim was that 20th-century Western culture was barreling toward the most hedonistic phase of sensate culture. His hypothesis seems to ring even truer in our time, as those disciplines have become untethered from the faith that once informed the culture that nurtured them.

Friedrich Nietzsche captured the widespread disorienting moral milieu in his most haunting words: “God is dead … and we have killed him.”

Writing in The Crisis of Our Age, Sorokin describes the emerging breaking point like this:

Instead of being depicted as a child of God, a bearer of the highest values attainable in this empirical world, and hence sacred, man is reduced to a mere inorganic or organic complex. … Since they are but a complex of atoms, and since the events of human history are but a variety of the mechanical motions of atoms, neither man nor his culture can be regarded as sacred. … In a word, materialistic sensory science and philosophy utterly degrade man and the truth itself.

As the sensate culture has marched forward in its decadence, there have been signposts along the road serving as memorial stones of those who have been the victims of the waywardness of the culture. In medicine and science, one of the many tragedies was brought into stark relief in the eugenics movement of the 19th and 20th centuries.

In the late 19th century, the theory of eugenics began to take root, promulgated by Francis Galton, who coincidentally was the cousin of Charles Darwin. The “survival of the fittest” fostered the belief that genetic superiority could be controlled and obtained through “judicious” mating based on race and physical attributes. This practice in the United States culminated in the second half of the 20th century through government-sanctioned involuntary sterilization in states like North Carolina, Virginia, Utah—and even California as late as 2010.

One victim of this heartbreaking departure from the Hippocratic Oath’s guardrails was Elaine Riddick, a black woman from North Carolina, who was involuntarily sterilized while giving birth in the 1960s. Elaine was 14 years old. Despite her pregnancy being the result of rape, she was deemed “promiscuous,” leading the North Carolina Eugenics Board to determine her unfit to procreate. It wasn’t until five years later, when she desired to start a family, that she learned what the doctors had done to her. Her story is not a lone example. Around 60,000 people were sterilized in 32 states across the country during the 20th century.

This grotesque crusade for racial and genetic purity wasn’t uniquely an American problem, as even a cursory review of World War II history will attest. The weaponization of medical care has a long and sordid history of bad-faith actors who have hijacked the very concept of care and twisted it into a cudgel to beat society into their hollowed-out vision of the common good. To highlight all the abuses that have littered history under the guise of healthcare is a project for another day, but let’s jog our recent memory a bit.

March 2020 marked the beginning of a wholesale societal shift whose results we will not fully realize for years. To look back on the pandemic’s peak and subsequent lockdowns is to experience a fever dream. The confusion over and fear of the unknown COVID virus, alloyed with the panicked, nonstop news reporting of overflowing hospitals, nursing homes, and makeshift morgues, only served to exacerbate anxiety and distrust.

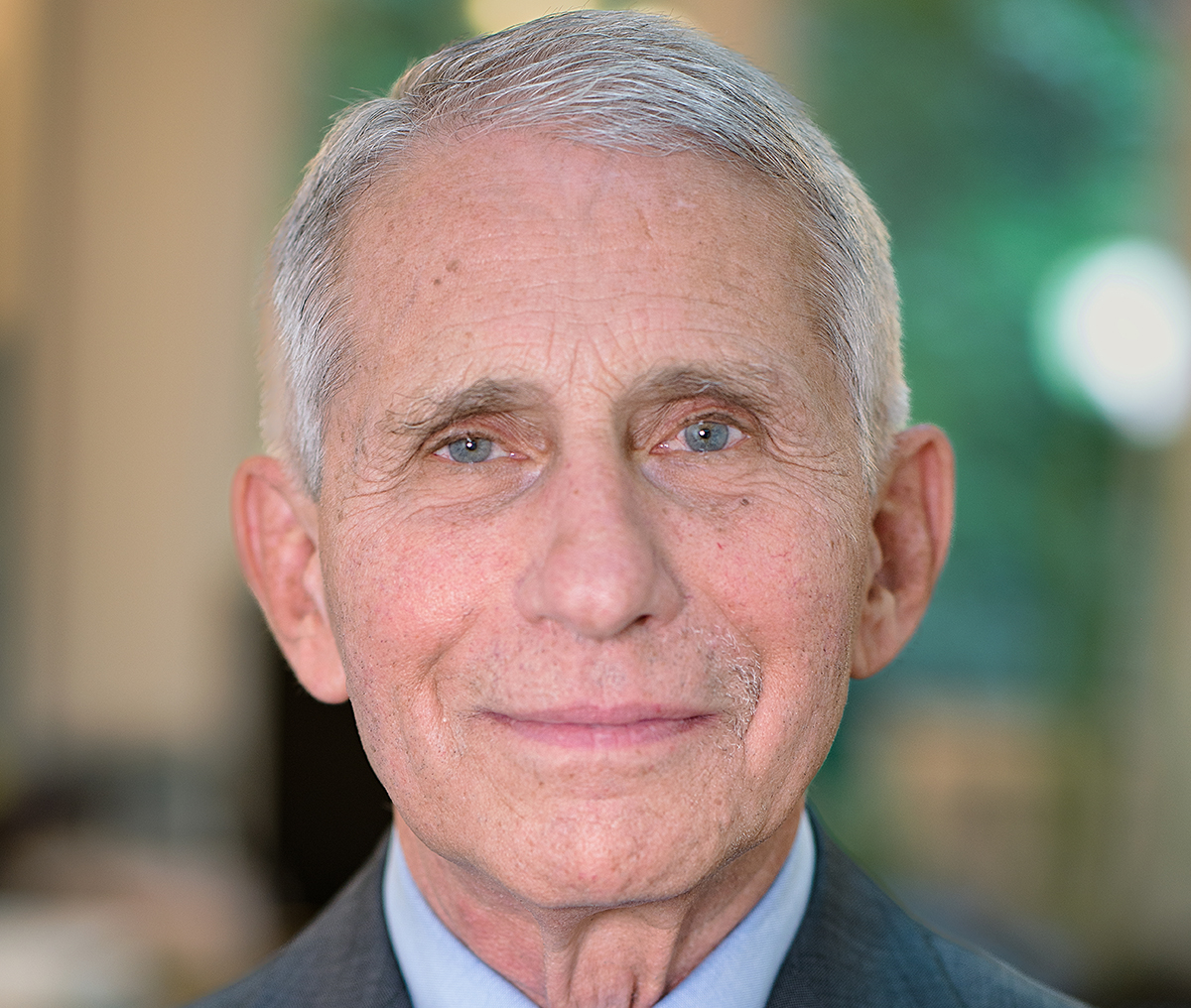

We are still reaping the whirlwind from the lockdowns imposed by state and local officials and encouraged by government-approved experts like Dr. Anthony Fauci. Many children are still trying to regain ground, both academically and emotionally, after their worlds were upended by remote learning. The mental health crisis only deepened, and any HR professional will tell you their jobs have become more complicated and fraught with landmines than ever before. Many people delayed preventative care and potentially lifesaving cancer screenings during this period. And that is to say nothing of those whose loved ones had to die alone in a cold and strange hospital room, with their families saying goodbye over a FaceTime call.

In a 2022 interview, Dr. Jay Bhattacharya, Stanford medical professor, health economist, and coauthor of the 2020 Great Barrington Declaration, shared his observations of the great public policy misses when it came to the U.S. government’s handling of COVID, particularly in managing risk among different populations. He noted the high level of COVID cases among the elderly in nursing homes, citing that it “came about because we were thinking about protection of hospital systems rather than protection of people.” This is a hallmark feature of Western medicine unmoored from virtue—when it has been stripped of its soul. Protecting systems becomes more important than protecting people.

Reflecting on the ways in which those in power during the COVID lockdowns wielded their authority, Dr. Bhattacharyacalled attention to the actions of individuals like Dr. Fauci and Dr. Francis Collins. One of their tactics in controlling the pandemic narrative was to create an “illusion of consensus that didn’t actually exist” among the medical community. “They wanted to create this idea that [it] was morally wrong to question public health,” Bhattacharya continued in the interview.

Innocent Americans were left to die in hospital rooms alone, devoid of any tenderness and comfort from their loved ones. Children with special needs did not receive adequate care. Adults who lacked support systems were left navigating depression in isolation, untouched and out of sight. After having breakfast and catching up with an elderly friend who battles severe depression—he is both a widower and disabled veteran—I gave him a hug as we prepared to go our separate ways. He told me that was the first time he had been hugged since the lockdowns. That was in August of 2022.

For all the ills imposed on citizens during the pandemic, including sweeping censorship that quelled dissent in both the physical and digital worlds as people were harassed for not wearing masks when at the grocery store, a post-pandemicpublic backlash has provided opportunity for scrutiny and accountability. For example, Dr. Fauci’s mural has been taken down from the National Institutes of Health, while Dr. Bhattacharya has been named its director.

Unfortunately, such reversals have not been in evidence in other medical currents, particularly in Canada, where the troubling acceptance of euthanasia only seems to be growing and reaching new depths.

In 2023, Canada’s parliament rolled out approval for euthanasia of non–terminally ill patients, putting its rubber stamp on someone electing to end her life if she felt as if it were too emotionally painful to continue on. This approval extended even to children.

Health Canada, which manages the nation’s health policy, recently released a report that revealed “47.1% of non–terminally ill Canadians who applied for MAiD cited ‘isolation or loneliness’ as one of the causes of their suffering.” Suffering with an incurable illness is an enormous burden for anybody to bear, but suffering from loneliness? Our spirits were not designed for it.

We live in a time when euthanasia and physician assisted suicide are widely accepted by the public, with 7 in 10 Americans stating they believe doctors should be “allowed by law to end the patient’s life by some painless means if the patient and his or her family request it.” In 1950, shortly after Gallup began polling this topic, only 36% of Americans supported it. The next time Gallup polled on the issue was 1973, when it saw a 17% increase in support. Coincidentally, this was also the year Roe v. Wade, guaranteeing abortion access, was enshrined in law.

Again, how did we get here?

In Paul Ramsey’s seminal lecture series, he asked, “What are the moral claims upon us in crucial medical situations and human relations in which some decision must be made about how to show respect for, protect, preserve, and honor the life of a fellow man?” This interrogation of medicine, asking what our moral duty and obligation are, is rare in our hyper-permissive economy, which typically views obligations of services through the lens of monetary cost and ability to pay. The difference can be distilled down to “What do I owe my neighbor” versus “What do I owe my customer?”

But medicine and healthcare were not always this way. In Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals, Guenter B. Risse describes medical care during the Middle Ages as deeply intertwined with religious beliefs and charitable practices. Hospitals in medieval Europe were primarily religious institutions, often run by monasteries, convents, and religious orders. Their main purpose was not necessarily to cure but to provide care, comfort, and spiritual healing to the sick, the poor, and pilgrims.

Hospitals were considered places of Christian caritas, where caring for the sick was a way to perform acts of mercy and keep the law of Christ. Given the significant limits of medicine during that era, the focus was on custodial care more than it was curative. Even so, despite our longer lifespans and ability to bypass the debilitating effects of what today are often minor health inconveniences instead of death sentences, there is something about the posture of the relationship between the earlier Church and medical care that the moderns can learn from.

St. John Chrysostom, the archbishop of Constantinople in the fourth century, said, “The Church is a hospital, and not a courtroom, for souls. She does not condemn on behalf of sins, but grants remission of sins.” This restorative approach to soul care was consistent with the Church’s commitment to physical care for the sick and needy. Even while Christianity was still in its cradle, it stood out among the rest of the ancient world in its willingness to risk comfort, and even life, in service of the suffering. While the pagans fled from plague, the Christians stayed to tend to the dying. When the Romans would leave an unwanted baby exposed to the elements to avoid responsibility, the Christians would rescue these precious children and raise them as their own.

There was no test of purity or worthiness required for admittance into the sick ward of both the hospital and the Church. In fact, if you weren’t sick or helping to alleviate suffering in some way, you had no business there. Access was available to all by virtue of being one of Christ’s lambs, and if He would leave the 99 for one who had gone astray, how could Christian charity turn anyone away? Christ’s words in Luke 5 give beautiful contours to who is qualified to receive His healing care: “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. I have not come to call the righteous but sinners to repentance.”

Where the Hippocratic Oath seeks to guide the moral conduct of the physician by requiring virtue, the Physician Charter places an emphasis on the social contract.

For all its benefits, specialists, and advances, the layers of our modern healthcare system do not allow for such clear and direct care. The complexity can be mind-numbing and healthcare policy is teeming with rules and exceptions to the rules. In many respects, this sophistication in healthcare has served patients well, allowing for significant specialization, major medical breakthroughs, and R&D investment into lifesaving drugs. But somewhere along the way, with a meaningful relationship with a doctor obstructed by paperwork, in-network/out-of-network nuances, and government red tape, the sick have become lost in a world far messier and more cumbersome to navigate than ever before.

The covenantal commitment to care that physicians are asked to agree to when graduating from medical school, best captured by the spirit of the Hippocratic Oath, is too often crowded out by insurance mandates, drug company interests, and perverse incentives thrown into orbit by hospital associations. The modern, diluted patient-provider relationship is something most of us simply accept as the price of care.

Even the Oath itself has changed and been reconstructed in myriad ways over the years, and only in rare cases is a modern version of the Oath taken. In 2002, the Physician Charter was published and adopted by over 100 medical boards and foundations. This charter captured the move away from virtue-based ethics that medicine has historically been rooted in and pivoted to a duty-based ethical approach. Where the Hippocratic Oath seeks to guide the moral conduct of the physician by requiring virtue of the oath taker, the Charter places an emphasis on the social contract and professionalism as understood in a 21st-century context. The Oath focuses on patient care, beneficence, confidentiality, and personal morality, while the Charter emphasizes professionalism, patient welfare, and social justice.

The covenantal, religious nature of the Hippocratic Oath, even in its original, pagan form, invoked moral duties upon the oath bearer, approaching healing not merely from a utilitarian mindset. Healing mattered because people mattered; their bodies were the holy containers of their sacred and eternal souls.

A meaningful relationship with a doctor has been obstructed by paperwork, in-network/out-of-network nuances, and government red tape.

Hospice physician and former medical school professor Dr. Philip Hawley Jr. interrogated the seemingly outdated Hippocratic Oath by contrasting it with today’s bioethical norms, asking why it is still of any consequence today. Hawley wrote:

So why does this oath of disputed authorship—which seems unduly concerned with the elder-care of teachers and completely overlooks key tenets of modern bioethics—remain such an enduring symbol of medical ethics?

Perhaps it retains its significance precisely because it eschews unbounded and nebulous principles like autonomy and distributive justice—the most beloved precepts of contemporary bioethics—in favor of overtly virtuous deeds. For all of its eccentric features, the classic Hippocratic oath is a virtuous covenant between physician and patient—virtue and covenant being two elements that are often missing from today’s medical-ethics deliberations.

From the beginning, healthcare and medicine have made moral judgments—judgments about who man is and how he deserves to be treated. The further society has moved away from an ethic that views individuals as image bearers of their Creator, the more inclined we are to treat others according to what is right in our own eyes, with our own fickle preferences becoming the tuning fork by which we evaluate ethics. This malignant mindset has permeated nearly every sphere of society, including healthcare. Medicine has moved away from its covenantal roots and is far more committed to transactions. This has led to a host of competing interests that stand to make the sick person—the very individual medicine was designed for!—only one of multiple stake- and shareholders a modern physician must consider.

But this is not the entire story. There are examples of courage and resistance in healthcare, exemplified by physicians like Dr. Bhattacharya and the many men and women who impose on themselves the virtuous standards required for neighbor love. Maybe new captains of healthcare industry are just on the horizon.