Many years ago, on an autumn day in my hometown of Istanbul, I received an email from a friend who lived in the American Midwest and frequented a mainline Protestant church. After kind greetings, he asked me for some advice. “To understand Islam better, I want to read a copy of the Qur’an,” he wrote. “Can you please recommend a good English translation?”

The person most frequently mentioned in the Qur’an is not who you’d expect. And he is just the beginning of a much-forgotten story: the Judeo-Islamic tradition.

I was happy to see my friend’s interest in my faith’s scripture and advised him to get his hands on The Qur’an: A New Translation by Muhammad Abdel-Haleem. Several weeks later, my friend wrote back. He had indeed bought a copy and read much of it. He was touched by the teachings of piety and ethics he came across in the Qur’an, while puzzled by some other themes. He was also, as he put it frankly, a bit troubled by some combative verses—but only to recall, in fairness, that his own scripture, particularly the Old Testament, had similarly harsh passages.

“But do you know what the biggest surprise was?” my friend wrote at the end of his long email. “That I was expecting to read about the life of Muhammad. But, instead, I read about the life of Moses more than anything else.”

Was he exaggerating?

No, he was quite right. The Qur’an indeed narrates very little about its own messenger, the Prophet Muhammad, at least in an explicit way. In more than 6,000 verses that make up 114 “suras,” or chapters, the name Muhammad appears only four times. When you read the whole Qur’an, you learn almost nothing about his birth, his upbringing, his early life.

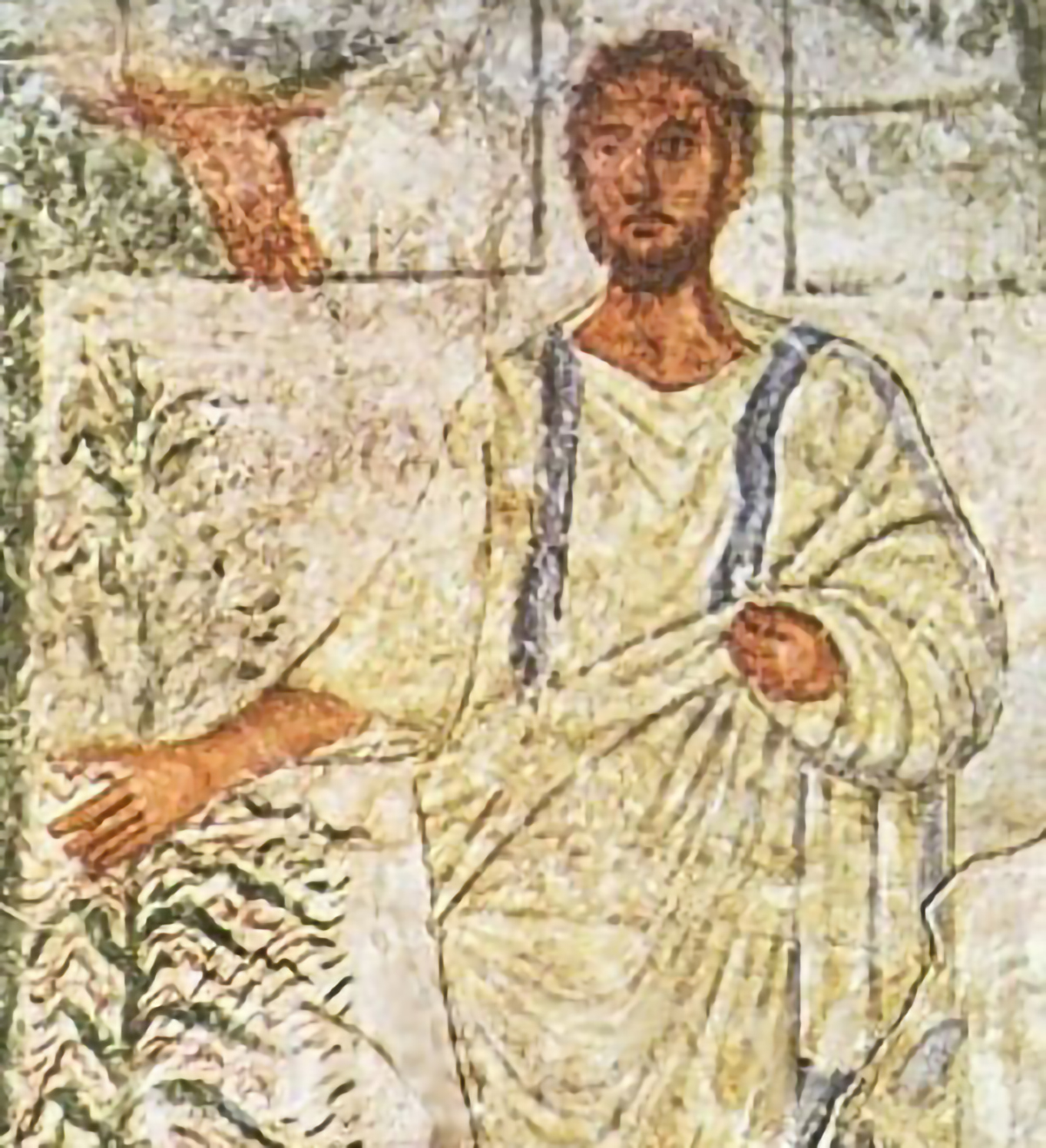

In contrast, Moses dominates the Qur’an. He is mentioned 137 times—more than any other human being by far. His story is narrated in some 70 passages dispersed throughout 34 separate chapters. When you read them all, you learn so much about Moses—from his birth in peril, to his leadership of the Israelites, to his defiance of the Pharaoh, to his amazing miracles. Therefore, when you read the whole Qur’an, you indeed learn about Moses more than anybody else.

Why is this the case? Why does the Qur’an narrate very little about its own actual Arab prophet? And why does it narrate so much about a bygone Jewish one?

The first question is easy enough to solve: The Qur’an does not speak about its own prophet because it speaks to him. Because the Qur’an presents itself as the word of God, transmitted by Angel Gabriel to Muhammad, whose primary function is to receive the divine revelation and to proclaim it to his people, the Arabs of early seventh-century Arabia. He is the “messenger,” truly, and not the message.

This second question also isn’t too hard to figure out. Moses is the most prominent figure in the whole Qur’an because he is the main historic precedent for Muhammad—the key inspiration for the example he follows.

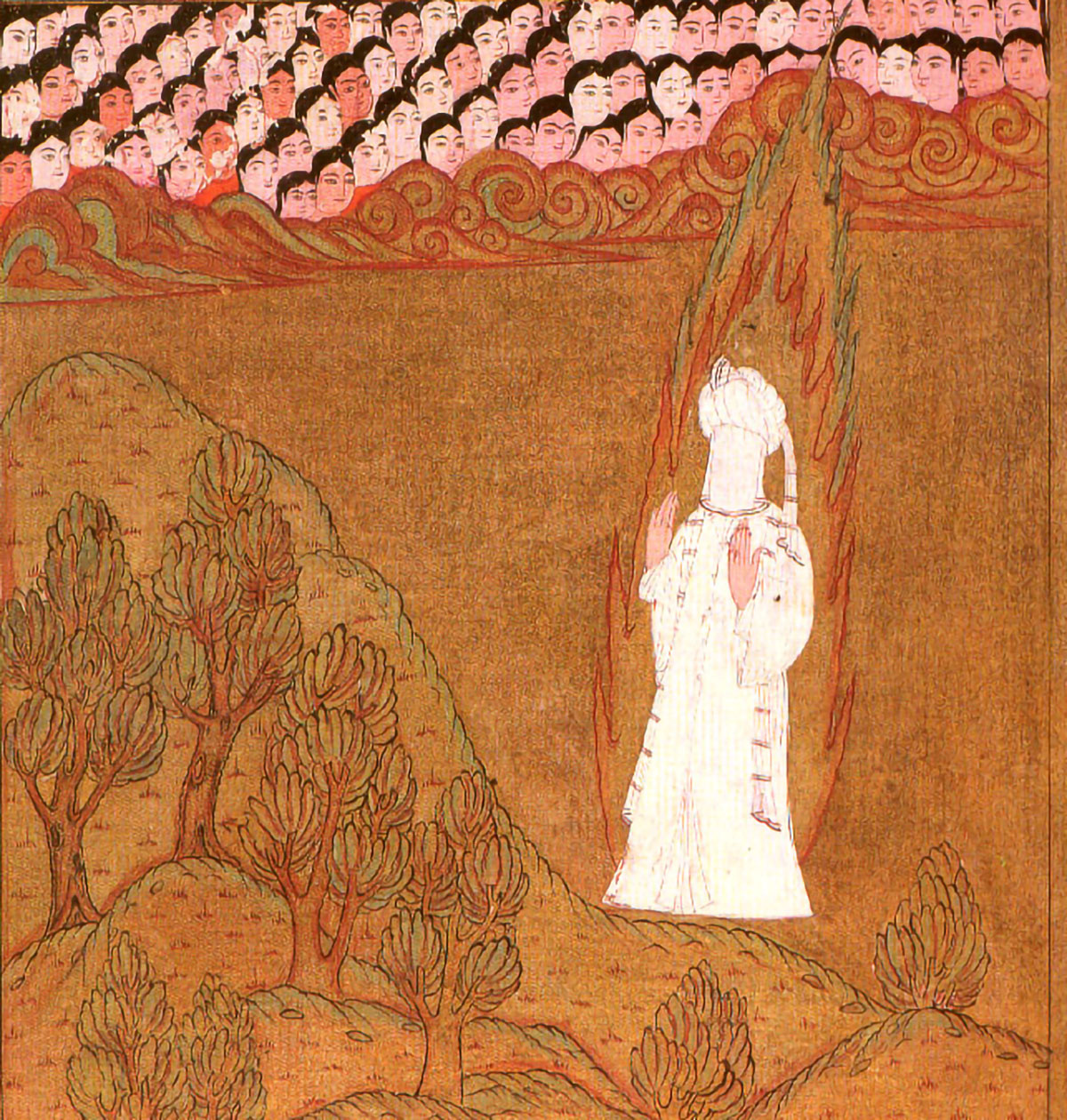

The parallelism between the two men is hard to miss. First, both were orphans who were adopted. Then both lived normal lives until a life-changing moment when they unpreparedly came face-to-face with the divine. For Moses, it was the burning bush on Mount Horeb. For Muhammad, it was the angelic voice on Mount Hira. Then new revelations formed the two scriptures these two prophets gave to their followers: for Moses, the Torah; for Muhammad, the Qur’an.

Yet neither Moses nor Muhammad merely transmitted sacred books. Both also delivered their followers from persecution to freedom. Moses and his fellow Israelites were persecuted by the Pharaoh of Egypt. Similarly, Muhammad and his fellow Arab monotheists—say, Ishmaelites—were persecuted by the polytheists of their hometown, Mecca. No wonder the Qur’an draws parallels between these two oppressors—the Egyptians and the Meccans—when it narrates Moses to Muhammad. And no wonder the oppression ends in a perilous escape for both: for Moses, the exodus from Egypt; for Muhammad, the hijra (“migration”) from Mecca.

And yet, in both stories, the journeys do not end with mere freedom. Moses and Muhammad also led bloody battles against deadly enemies, conquered new lands, and used coercive power to impose religious laws. In fact, they each established what political scientists call a “theocracy.”

One Western scholar of Islam who noted this parallelism between the journeys of these two prophets was the late Patricia Crone. Moses, she observed, is the “paradigmatic prophet” of the Qur’an. Because

wittingly or unwittingly, Muhammad was a new Moses. Like him, he united scattered tribes in the name of God and led them on to conquest. … Moses was an inspiration to many people, but his admirers were not usually able to imitate him in any literal way since they lived under such utterly different conditions. This was where Muhammad differed. He could and did re-enact Moses’ career.

In comparison, Jesus Christ, or Isa al-Masih, who is also highly praised in the Qur’an along with his mother, Mary, does not seem to be a role model for the Prophet Muhammad. For while the Qur’an tells us a lot about the supernatural birth of Jesus and his own miracles—while framing them in its own “low Christology”—it says nothing about his political journey. Not a single Qur’anic verse mentions Jesus’s ordeal with the Romans, which ended not with conquest and victory but rather in a painful earthly defeat. In fact, in just one verse, 4:157, the Qur’an mentions the archetype of that earthly defeat—the Crucifixion—but only to assert that it was not really a defeat.

For those familiar with the secular history of the world’s major religions, all this may rightly fall into place. That history tells us that monotheism—belief in one God, as opposed to polytheism, belief in many gods—developed first among the small nation of Israelites but then had two major expansions that reshaped the whole world.

The first major expansion was Christianity. Not too surprisingly, it was born among the Israelites themselves, when one of them, Jesus of Nazareth, began to spread “good news.” He was speaking to his fellow Jews, yet his message, and persona, was so powerful that it soon began winning hearts and minds among the gentiles. In a few centuries, it was also winning over the Roman Empire, and it ultimately became the world’s largest religion.

Moses dominates the Qur'an. He is mentioned 137 times—more than any other human being by far.

It should not be missed, however, that Christianity universalized Jewish monotheism only by departing from it in two significant ways.

The first departure was the notion of the divine Christ and the consequent doctrine of the Holy Trinity, which were unthinkable in the staunchly monotheistic Judaism, as they still are today. The second departure was the claim that the Mosaic law, or halakha, had now been superseded. “A person is justified not by the works of the law,” proclaimed Saint Paul, the eminent apostle, “but through faith in Jesus Christ.”

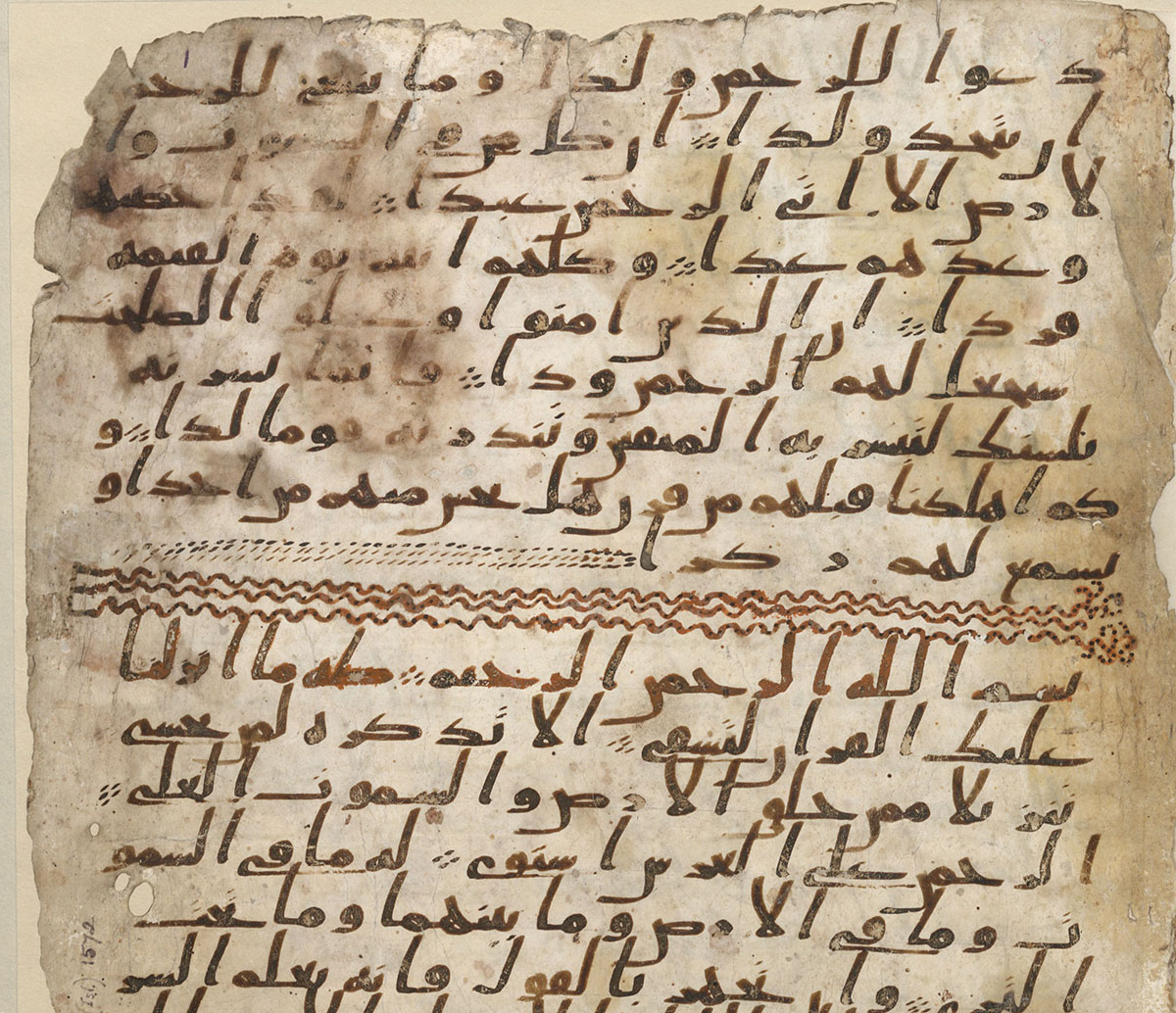

Then, almost six centuries after the birth of Christianity, came the second major expansion of monotheism, which was of course Islam. The Qur’an clearly defined itself as a revelation from the God of Abraham, “confirming what came before it,” namely, “the Torah and the Gospel” (3:3). It also proclaimed its version of the Ten Commandments, leaving aside only the Sabbath.

However, Islam did not follow Christianity in the ways the latter had departed from Judaism. First, theologically, it rejected the notion of a divine Christ and reverted to the strict unitarian monotheism of the Jews. Second, Islam, like Judaism, established a comprehensive legal tradition that governs both religious and worldly matters. The Jewish halakha, in other words, had a rebirth as the Islamic sharia.

Today this may sound surprising to many in the West, because the penal codes of these premodern legal systems, which include corporal punishments, have become largely obsolete in Judaism but are still in effect in Islam. (In other words, stoning—a punishment rooted in the Bible—is no longer practiced in the name of Judaism but can still occur in the name of Islam in countries like Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Afghanistan.)

Yet this difference is largely due to the different political trajectories of Judaism and Islam: One ceased to be a state religion two millennia ago, while the other remains so. Conceptually, however, halakha and sharia are unmistakably similar. No wonder the great medieval Jewish scholar Moses Maimonides did not shy away from using the very term sharia for Jewish law in his writings in Judeo-Arabic. And no wonder today Muslims and Jews living in the West can find commonalities in their kosher and halal cuisines, and practices such as male circumcision.

There is something else that may also sound surprising to many in the West today: The theological affinities between Judaism and Islam initiated a centuries-long coexistence for the two religions. It even created a “Judeo-Islamic tradition,” as the late, great historian Bernard Lewis once called it in his 1984 book, The Jews of Islam.

This much-forgotten tradition, which I highlight in my book The Islamic Moses, began with the very genesis of Islam. One of Muhammad’s remarkable achievements was a political pact he formed in the city of Medina, the destination of his hijra, soon after his arrival in 622 CE. This was a charter established by the first Muslims and joined by various tribes in the city, some of which were composed of Jews. It has a remarkable clause that reads: “The Jews have their religion, and the Muslims have theirs.” Jews, in other words, were not compelled to accept Islam but were free to practice their religion along with Muslims.

This “Constitution of Medina,” as some Muslims call it proudly today, would later tragically collapse—but due to political conflicts, not religious ones. Even still, Islam, which detested idolatry, would keep affirming the legitimacy of Judaism, as well as that of Christianity. Hence their followers, called “People of the Book,” would be given the right to practice their religion under Islamic rule, despite some legal limitations.

That is why when Muhammad passed away in 632 and his “successors,” or caliphs, launched a religious empire that expanded with conquests, most Jews welcomed this new religion, which seemed remarkably tolerant for its time. The alternative they knew, medieval Christendom, was a far cry from today’s “Judeo-Christian” West, with many anti-Jewish teachings and laws. Hence Muslim victories against Christian powers, from the Byzantine Empire to Visigothic Spain, were welcomed by Jewish communities, if not even actively aided by them.

Jews were particularly delighted by the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem in 638 by the second caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab, as he not only allowed but also facilitated their return to their holy city after centuries of banishment. Hence a seventh-century Jewish text, The Secrets of Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai, depicted the rise of Islam as the fulfillment of Jewish messianic hopes.

The formation of the Islamic empire in the seventh century initiated centuries of Jewish-Muslim coexistence—or even “symbiosis,” as it was described by the 20th-century Jewish historian Shelomo Dov Goitein. Jews had golden ages of safety and prosperity in the Middle East, North Africa, and Muslim Spain. According to Rabbi Joseph Telushkin, “the Golden Age of Spanish Jewry,” which spanned the 10th to 12th centuries under “remarkably tolerant Muslim leaders,” can even be regarded as “the closest parallel in Jewish history to the contemporary golden age of American-Jewish life.” There were also some darker episodes of persecution, which are cherry-picked by some today. But they were “atypical and rare,” as described by Bernard Lewis.

During these medieval centuries, Islam and Judaism, with very similar theologies and practices, even learned a lot from each other. Muslim scholars studied texts they called Israʼiliyyat, or “of the Israelites,” which contributed greatly to Islamic exegesis. Meanwhile, Jewish scholars such as Dawud al-Muqammis (d. ca. 937) and Saadia Gaon (d. 942) studied kalam, or Islamic theology, and incorporated it into their own tradition. No wonder “the emergence of a Jewish theology took place almost entirely in Islamic lands,” as contemporary scholar Aaron W. Hughes puts it.

The great medieval Jewish scholar Moses Maimonides did not shy away from using the very term sharia for Jewish law in his writings in Judeo-Arabic.

Greek philosophy became another tradition that connected Jews and Muslims. “Medieval Jewish philosophy,” as noted by Encyclopaedia Judaica, “began in the early tenth century as part of a general cultural revival in the Islamic East.” Works of Muslim philosophers such as al-Farabi and Ibn Sina were appreciated and studied Jewish counterparts such as Moses Maimonides. Their engagement with Islamic rationality also helped preserve some of the latter’s wisdom. Today it is a remarkable irony that some of the works of the rationalist Muslim theologians, the Mu’tazila, and the greatest Muslim Aristotelian philosopher, Ibn Rushd (Averroes), are available to us via Hebrew translations, while their Arabic originals are lost. (And why that is the case is an intriguing question I explore in my book.)

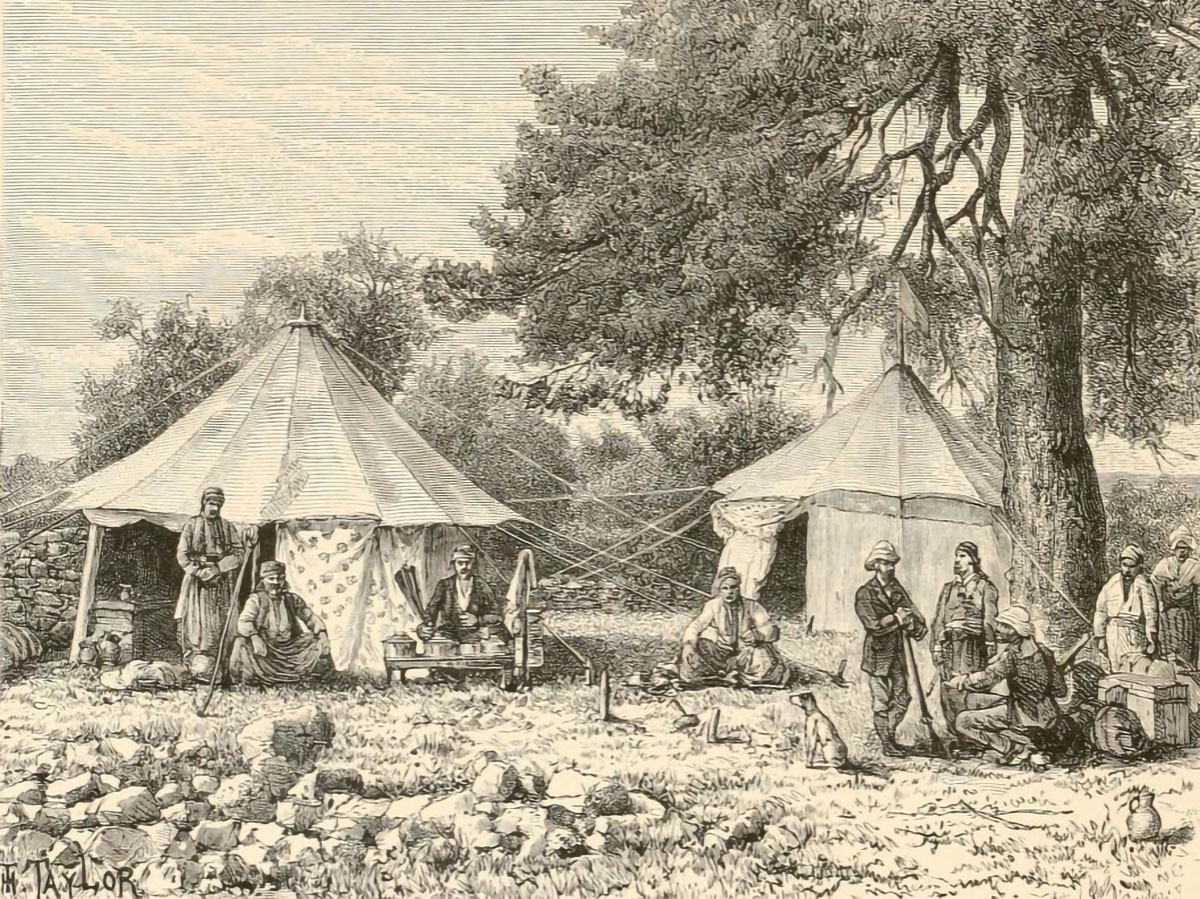

The final bright chapter of the Judeo-Islamic tradition takes place in the Ottoman Empire, the last seat of the Islamic caliphate, which repeatedly offered safe haven to persecuted Jews. Among them were Sephardic Jews, who were expelled from Spain in 1492, at the time of Columbus, only to find the best future for themselves in the Ottoman lands. Some Ashkenazi communities persecuted in Europe also found refuge in the Ottoman Empire. Among them was Rabbi Yitzhak Sarfati of the 15th century, who called back to his coreligionists in Germany to leave that “accursed land” and come to Turkey, “where every man may dwell at peace under his own vine and fig tree.”

Meanwhile, Ottoman Palestine was home to Muslims, Jews, and Christians, who lived together peacefully. That is why an 18th-century Polish immigrant to Hebron, Rabbi Abraham Gershon, was amazed to see that, in the Holy Land, Jews “have virtually no fear of gentiles.” And that is why in the 19th century, as historian Alan Dowty notes in his book Arabs and Jews in Ottoman Palestine, “none of the observers at the time foresaw the conflict that was yet to come.”

The conflict did come, however, owing not to “ancient hatreds” but to a modern force: nationalism, the urge to create ethnically defined nation-states in diverse territories. This drive created much bloodshed in all former Ottoman territories, beginning with the Balkans and extending to eastern Anatolia.

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict—which escalated to its darkest phase on October 7, 2023—is yet another chapter in these bitter struggles between two peoples who claim the same land. It is not a religious war, in other words, but a national one. And it will happily end only when we can somehow make the two people peacefully coexist on that precious land, “from the river to the sea,” instead of just claiming it for themselves.

This has clearly been impossible so far. Moreover, this national conflict eclipsed the Judeo-Islamic tradition. Rather than acting as a bridge, religion began to exacerbate zealotry on both sides. For religion is at its worst, everywhere, when it sharpens the us-versus-them divisions, stoking hatred, militancy, and bloodshed.

Yet religion can still offer its best, too, when it evokes a common humanity and preaches empathy, mercy, and peace. Fortunately, both Judaism and Islam have the resources to do that. Moreover, Jews and Muslims have a shared tradition to remember. They have a bitter land dispute to resolve, of course, but also a theological affinity to recover—as the worshippers of the same God, the fellow children of Abraham, and the kindred followers of Moses.