Religious revivals have been a part of the American historical landscape even before the republic existed. Most were linked and intertwined with other social movements happening at the time. The First Great Awakening (1730s to late ’40s) challenged people to take their Christian faith seriously and apply it in their daily lives, leading to the creation of new educational institutions and organizations, not to mention schisms in existing denominations owing to the conflict between the “New Lights” (revivalist) and the “Old Lights” (traditionalist). Many of these reignited religious movements resulted in radical social change and planted the seeds of the American Revolution and, eventually, abolitionism.

Is America’s tech hub becoming born again? It wouldn’t be the first time religion and burgeoning technology paired up to change the world.

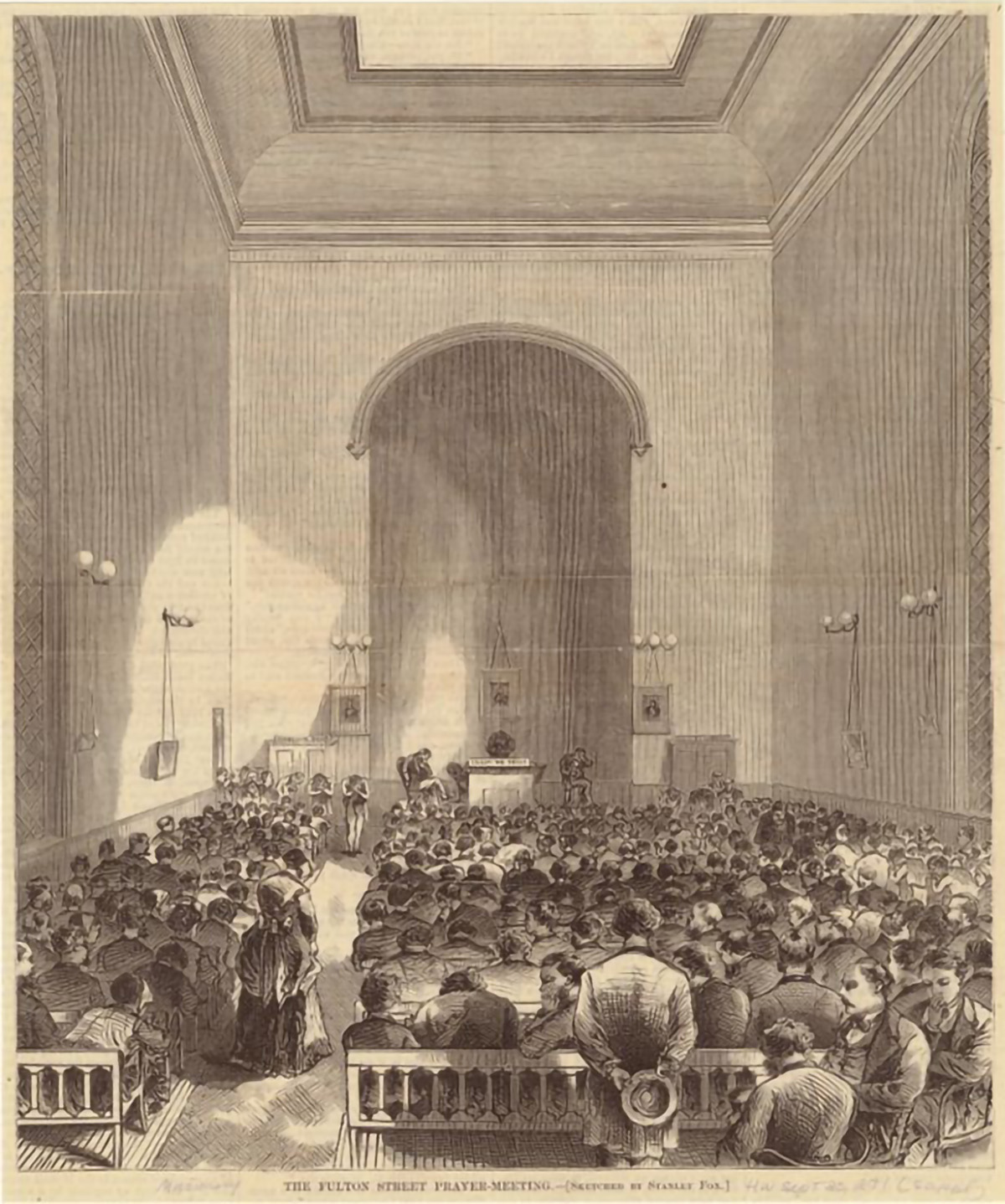

Another significant religious renascence was the “Businessman’s Revival” of 1857–58 in New York City. Jeremiah Lanphier, a lay minister with the North Dutch Reformed Church, initiated a small prayer group for businessmen. While starting modestly, his noontime prayer vigils in and around New York swelled to tens of thousands within just two months. Most historians link the stock market panic of 1857 as a significant social instigator for this revival, which eventually spread throughout the nation.

Social change, especially within the past 225 years, has often been directly linked to technological change. The effects of mechanization and industrialization on the workforce have always had significant cultural impacts, especially as the benefits are not always evenly distributed. Regional centers of economic power throughout this period were in flux in significant ways, as both the materials produced and new means of producing them underwent remarkable changes.

Today it is fair to say that one of the most powerful centers of economic power and social influence in the world is Silicon Valley. Studying the history and impact of this region is easily traced through the creation of Stanford University, the vision of Hewlett-Packard in the late 1930s and extending to the Shockley/Fairchild Semiconductor inventions of the late 1950s. One would be remiss to think that the influence of the valley over the past 75 years has been merely technological. The vast innovation, creativity, and industry incubated in this small territory and its impact on the world is hard to grasp. And just like many culturally significant moments before it, there seems to be a revival brewing in Silicon Valley right now.

Much ink has been spilled explaining the idea that the pace of technological innovation and change originating in America has been so mesmerizing that it is evolving into a religion of its own. In fact, historian David Nye, in his classic work American Technological Sublime, insists that technological progress is America’s civil religion. Or as the social theorist L.M. Sacasas summarizes:

Historically Americans have been divided by region, ethnicity, race, religion, and class. Americans share no blood lines and they have no ancient history in their land. What they have possessed, however, is a remarkable faith in technological progress that has been periodically rekindled by one sublime technology after another.

Carolyn Chen engages this issue more fully in her book Work, Pray, Code. Talking primarily about the sociological benefits of religion, Chen argues that:

workplaces have become the new “faith communities” of Silicon Valley. It’s through work that tech workers find identity, meaning and belonging—the social and spiritual needs that Americans once turned to their religions to fulfill. This creates a particular kind of ecosystem where the members of that society worship a theocracy of work.…Today’s tech companies really understand this. As some say, “Meaning is the new money.” I call this shift the “spiritual turn in management.”

Whether or not one consciously worships technological innovation or is simply attracted to the social practices that mimic religious observance in the contemporary workplace, the undeniable fact is that any serious person who thinks about the implications of modern advances in communication, transportation, and automation must eventually consider “spiritual” questions. What does it mean to be human? What is consciousness? What is the best definition of community, and what are its benefits? Is there a transcendent Creator God, or can we create one in our own image here and now? To the extent that there were spiritual undertones in Silicon Valley previously, however, they tended to be eastern, especially Buddhist, or some variation of altruism, but rarely specifically Christian.

In fact, some argue that San Francisco in general, and Silicon Valley in particular, has been hostile to Christianity for years, even parodied most famously in the HBO show Silicon Valley:

Jared: You can be openly polyamorous and people here will call you brave. Put microdoses of LSD in your cereal and people will call you a pioneer. … But one thing you cannot be is a Christian.

Bertram: I find their theology to be illegitimate, and it’s clear that they’re the source of the majority of the world’s problems. But, f---, Richard, even I wouldn’t just out a Christian.

Now that seems to be changing.

There appears to be a specifically Christian revival taking place in tech communities throughout the Bay Area. A flurry of recent articles in The New York Times, Wired, and even Vanity Fair, though closely parroting each other, regard the open ascendancy of Christian founders, funders, and budding entrepreneurs as a new wave of spiritual enlightenment.

Vanity Fair describes it this way:

You don’t need to do much guesswork to see why smart Christians in Silicon Valley are growing more emboldened. After all, there are billionaires among their ranks. One of them is Peter Thiel, who has spoken about his evangelical leanings for more than a decade and who has lately shared his views on his faith with increasing frequency. “I believe in the resurrection of Christ,” he said in a 2020 talk. “The only good role model for us is Christ.” … And it’s not only Thiel. Last summer, in an interview with Jordan Peterson, Elon Musk described himself, cautiously, as a “cultural Christian.” “I do believe that the teachings of Jesus are good and wise,” he said. To have two of the world’s richest technologists, worth a recently estimated $400 billion (Musk) and $14 billion (Thiel), speak admiringly about biblical teachings challenges the view that Christianity is anti-capitalist or even anti-intellectual.

This shouldn’t be that surprising. What is happening in Silicon Valley is a continuation of the fascinating relationship between religion and technology that has a very long history.

A ninth-century illuminated manuscript known as the Utrecht Psalter is an early example of technology and religion intersecting. The Psalter’s illustration of Psalm 64:2–3—“Hide me from the secret plots of the wicked, from the throng of evildoers, who whet their tongues like swords, who aim bitter words like arrows”—depicts God’s people sharpening their swords on a newly developed technology, the grindstone, while evildoers rely on the old-fashioned technology of the whetstone. God was on the side of new technologies and progress. As the Utrecht Psalter made its way around medieval Europe, religious communities bought into the idea that technological progress was God-ordained and a means of either restoring Eden or, at the very least, ushering in a new age.

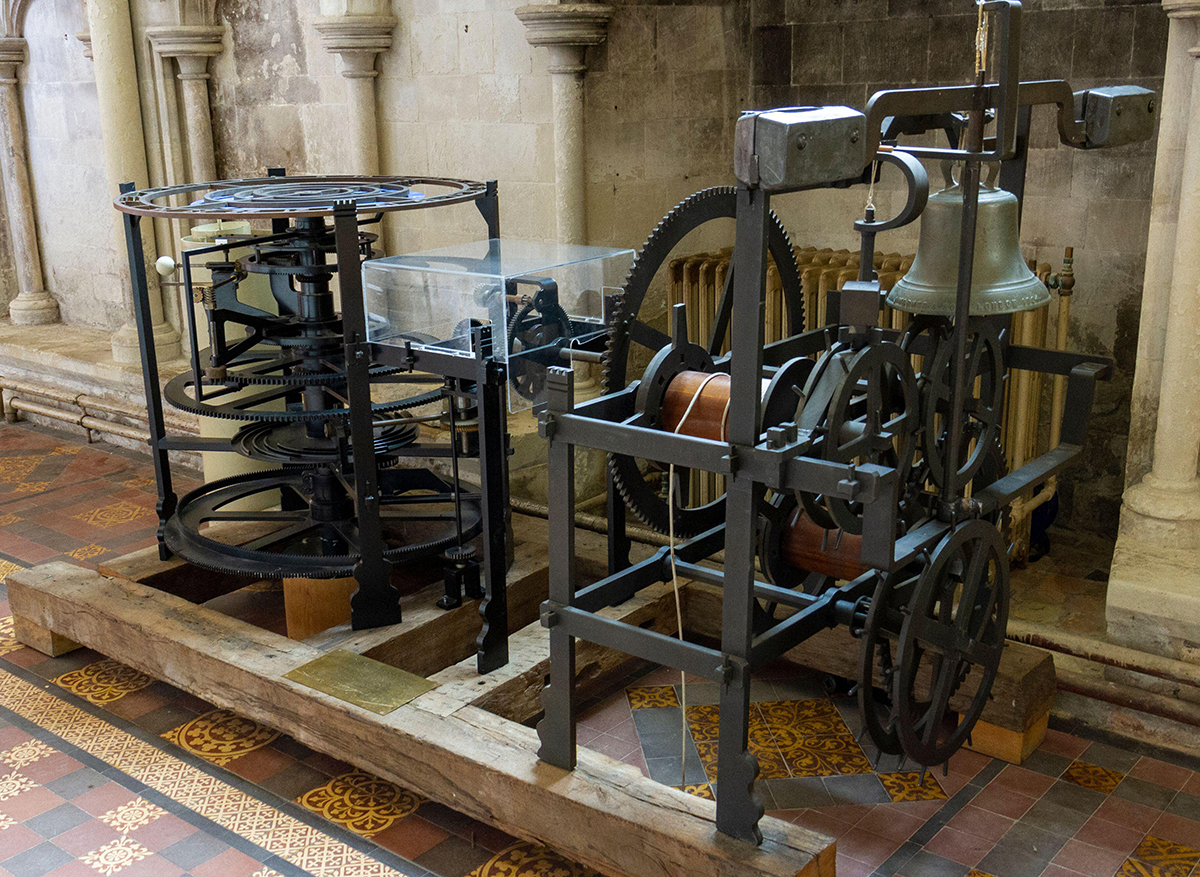

Soon thereafter, Benedictine monks in the 12th and 13th centuries brought technology and religion together as they developed mechanical clocks to regulate times of prayer and worship. Even before they had invented these devices, Benedictine monasteries functioned with clock-like regularity and efficiency, as unvarying times of work, prayer, and rest ordered each and every day. It was therefore not a stretch for the monks to forge from their religious rule and order technological devices like the mechanical clock.

But it did not end there—the monks created other labor-saving machines to free up time for meditation and prayer. The historian of technology Lewis Mumford, in his book The Myth of the Machine: Technics and Human Development,describes the ways in which religion and technology went hand-in-hand for the Benedictines: “A whole series of technological advances had been instituted by the Benedictine monasteries which released labor for other purposes and immediately added to the total productivity of the handicrafts themselves.”

The Reformation contributed to the fusion of religion and technology. In 16th-century Germany, Martin Luther placed the sermon at the center of the worship service and made reception of God’s Word a vital point of orientation for the life of the church. This turned the pulpit into a powerful means of public discourse. According to Andrew Pettegree, in his book Brand Luther, the Reformation could not have occurred without print: “Luther and his friends used every instrument of communication known to medieval and renaissance Europe: correspondence, song, word of mouth, painted and printed images.”

Prior to Luther, the success and influence of the printing press was tenuous and speculative. It was not entirely clear to publishers how the printing press could be used to sell large volumes of a book and thereby become a profitable endeavor. The printing industry, however, found a solution in the collaborative efforts of Martin Luther and the artist Lucas Cranach. Luther supplied the words while Cranach supplied the images. Cranach’s visual rhetoric—namely his woodcuts and innovative cover designs—transformed the look of Wittenberg books and helped them appeal to a very wide audience.

Thus the burgeoning technology of the printing press found its kairotic moment in the Reformation. Pettegree argues that religion propelled this new technology, as Luther was able “to grasp an opportunity that had scarcely existed before he invented a new way to converse through books. In the process he changed Western religion and European society forever.” The printing press languished until religion helped make full use of this technology.

Later advances in science and technology built on these interactions between religion and technology and generated newfervor and even language. Francis Bacon (1561–1626) understood science and religion as complementing each other as part of a common effort to bring about God-ordained dominion and spiritual redemption. For Bacon, religion addressed the moral corruption that came from the Fall, while science and technology dealt with the natural corruption that resulted from the curse that followed hard upon it. So religion handled matters of dominion over the self while science and technology handled matters of dominion over nature. In this view, religion was incomplete or deficient without science and technology.

Thomas Hughes, in his book Human-Built World, describes how yet others took up the Baconian hope for technology to bring about benevolent dominion and regain paradise. Hughes argues that the lineage of medieval monks, the Puritan work ethic, and Bacon’s dualistic redemption through religion and technology took on a new shape among American settlers. These pilgrims bought into the notion of technological progress as the means of recovering Eden and creating a technological City on a Hill, a light for the world.

It was therefore not a stretch for the monks to forge from their religious rule and order technological devices like the mechanical clock.

John Adolphus Etzler offers us a vivid depiction of the religious hopes for science and technology in that time. Etzler’s book The Paradise Within the Reach of All Men, Without Labour, by Powers of Nature and Machinery: An Address to All Intelligent Men (1836) is a paean to human reason and technological progress. Etzler writes:

If man ever forfeited the paradise by his sin, as we are told, it must have been the sin of neglecting the most precious gift of his Maker, that reasoning faculty, that only gives him dominion over the brutes, and may give him also the dominion over the inanimate creation, and make thereby the earth a paradise. Man needs not to eat his bread in the sweat of his brow, and to pass his life in drudgery and misery, except he perseveres in his mental sloth, and foregoes the use of his reason.

So it should come as no surprise—nor is it entirely novel—that today’s Silicon Valley technologists imbue their work with a religious fervor and language. Rather, these technologists are just the latest iteration of something that goes as far back as medieval monasteries and illuminated manuscripts, Francis Bacon and Manifest Destiny.

Since we have seen similar occurrences in history, what should we make of this Great Awakening in Silicon Valley? Is this a dangerous misappropriation of Christianity whereby technologists are exploiting religious categories and language for profit? Or could this be a beatific moment when Silicon Valley is truly seeing the light and finding Jesus?

A certain degree of caution should sober our excitement around this phenomenon. Silicon Valley technologists are besotted with new forms of AI and implanting computer chips into brains. Yet, despite their extraordinary ingenuity, it is far harder to invent entirely new idols and heresies. What is happening today in Silicon Valley brings to mind the warnings of Scripture and church history.

In his Institutes of the Christian Religion, the Reformed theologian John Calvin famously noted, “Man’s nature, so to speak, is a perpetual factory of idols” and “The mind begets an idol, and the hand gives it birth.” Similarly, Martin Luther taught that an idol or a false god is anything that man fears, loves, and trusts above all else. These Reformation-era insights illuminate how some in Silicon Valley are merely worshipping idols of their own making.

Way of the Future is a perfect example. This self-proclaimed AI-worshipping religion was created by former Google AI engineer Anthony Levandowski. Way of the Future was founded in 2017 and is registered with the IRS as a church. The religion seeks to promote “the realization, acceptance, and worship of a Godhead based on Artificial Intelligence (AI) developed through computer hardware and software.”

Something like Way of the Future brings to mind the words of Psalm 115:4, 8: “Their idols are silver and gold, the work of human hands.…Those who make them become like them; so do all who trust in them.” The idolatry of long ago, in the biblical world’s Kidron Valley and Jezreel Valley, is reappearing in Silicon Valley. There really is nothing new under the sun.

Silicon Valley’s religious impulses also have gnostic undercurrents, which the early church resisted. The second-century heresy of Gnosticism, while taking different forms, was nevertheless deeply suspicious of the material world, and thus of the human body. According to the gnostic sects, a malevolent and inferior deity is responsible for imprisoning humankind in their physical bodies. Yet superior persons can be released by secret “gnosis,” or knowledge, that enables communion with the immaterial realm, and “salvation.”

Silicon Valley’s hopes for reaching the “technological singularity”—the point at which computers attain consciousness and independent intelligence—is not too far from the gnostic conception of heaven, known as “the pleroma” (Greek for “fullness”). Uploading one’s consciousness into a computer, thereby achieving a kind of immortality, is just a 21st-century version of the oldest heresy.

Recently, Peter Thiel delivered sermons on multiple occasions explaining why he is a Christian and the idea of forgiveness and the power of miracles.

And yet … one could construe Silicon Valley’s “Christian” turn as at least headed in the right direction. The religious conversations happening in the valley can provide opportunities for serious theological reflection, something meatier than vague, amorphous “spirituality” and the attendant cliches. There certainly needs to be much more openness to discussions early in the research and development process about the deep moral implications of what is being conceived and ultimately funded. For example: Does this technological innovation promote human flourishing or diminish it? Can we even know what such flourishing would look like if we do not first know man’s purpose for being? And is that identifiable without acknowledging a Creator in whose image he is made? From there, more specific questions can be addressed, such as: Should we be spending billions of dollars on autonomous weapons for the defense industry given the risk of mass destruction?

In short, there need to be counternarratives to the ones proposed by the likes of Sam Altman, who believes artificial general intelligence will give humans “God-like” powers and eliminate any desire for the divine. Theologically speaking, many Silicon Valley projects have anthropological, soteriological, and eschatological implications, and reflection on the front end can lead to more prudent and responsible technologies on the back end.

One organization doing the good work of advancing sincere religious dialogue in this space is AI and Faith. Their mission is to

envision a world where the effects of technology are exclusively life-affirming, promoting the dignity and wellbeing of all humans and improving their interactions through meaningful community and a just society. As a result, we encourage, connect and equip people to bring the fundamental values of the world’s major religions into the emerging debates about the ethical development of AI-related technologies.

This approach provides a fruitful way forward for religiously minded people involved in technology creation and adoption to avoid the raw instrumentalizing of people as part of their craft.

Like most revivals before it, the uptick in conversations and gatherings regarding Christianity in Silicon Valley are largely personality driven. Recently, Peter Thiel delivered sermons on multiple occasions explaining why he is a Christian and the idea of forgiveness and the power of miracles. Garry Tan, the CEO of Y Combinator, arguably the most impactful start-up accelerator in the valley, helping to launch over 4,000 companies, is also a major draw at recent events marketed specifically as Christian programs.

In an industry prone to fads and hype, the power of influencers should not be overlooked. Are people really interested in the power and work of Jesus Christ, who was not merely a great teacher but the Son of God who atoned for our sins and now sits at the right hand of God the Father, interceding on our behalf? Or is this about getting close to the people who, if you adopt their philosophy of life, might get you another round of funding?

While the staying power of this “Silicon Valley revival” remains to be seen, we know from history that the longer a revival lasts, and the more people there are attracted to it, the more significant the impact it will have on the social fabric of a region and industry. This is what might set this apart from revivals of the past. The speed and scope of change in this sector is like nothing we’ve seen before: It’s another example of the technology multiplier effect—influence and creativity compound just like interest.

As with the printing press, the spread of the gospel is often inextricably linked, with varied degrees of success, to technological innovation. And as media theorist Henry Jenkins has posited, “The history of new media has been shaped again and again by four key innovative groups—evangelists, pornographers, advertisers, and politicians, each of whom is constantly looking for new ways to interface with their public.”

We have obviously seen the massive effects of three of those groups on the social ecology of modern culture. Maybe it’s time for the evangelists to do their work.