Human beings will always have work. It is part of the human condition. Work itself is a good that is part of God’s original design and therefore contributes to human flourishing. And while work and calling do overlap at times, they are not the same (as I will keep repeating throughout these pages). Perhaps recognizing how they are different can help us appreciate what each is and what role each has in our individual lives and in our communal life together.

You also have a job, a career, a side gig, a position, an occupation. But is any of them your calling? If not, how do you find meaning in work?

We were created to work—just as our Creator works—and that work will be part of the new heaven and the new earth. Understanding that can give us the perspective that work will never end—not because it’s bad but because it’s good. Even so, the nature, meaning, and role of work shift due to the changes that take place within larger social frameworks—even from one generation to the next. Moreover, there are infinite kinds of good work we might do.

Having many possibilities is liberating. But as anyone who has experienced the fear of missing out or analysis paralysis knows, it can be crippling too. Life in the modern world is characterized by, among other things, an increased sense of individual agency and responsibility for our lives compared to previous times. This increased sense of responsibility makes our decisions around work more fraught and anxious in a way our ancestors, who had few or no choices, did not experience. The medieval person born into a peasant family and their peer born into royalty knew their calling. Most of us today don’t, at least not at first. Perhaps not ever. ...

The Reformation’s emphasis on the significance of all types of work created new social and economic opportunities for work. What resulted were conditions in which one’s labor could generate economic benefits for oneself, not only one’s lords and rulers. Work undertaken for self-interest naturally leads to motivation to work harder and better, a phenomenon that in great part defines the modern condition and the rise of the modern individual. Work in such cultural circumstances becomes not merely a necessary calling based on the circumstances of one’s birth but also an opportunity for advancement and improvement.

Daniel Defoe’s 1722 novel Moll Flanders illustrates the changing nature of work in the modern age. This fictional story is presented as a true memoir of a woman who, born in Newgate prison to a convict, scrambles her way through life via her own pluck and resourcefulness. The story centers on the various kinds of work Moll does (much of it illegal) in order to survive and ultimately thrive. She reaches the end of her life wealthy and penitent, having employed herself along the way as servant, mistress, swindler, and thief. Defoe shows how Moll understands herself and the conditions of her life in the language she uses to describe her work. She softens the criminal aspects of her career by using euphemistic language. She calls her forays out onto the city streets to steal “adventures,” “excursions,” or taking “a walk.” She describes skills in robbery as an “art,” a “craft,” and the “trade,” and she calls her fellow thieves “artists.”

Now, Defoe is making a great deal of social (and religious) commentary in this story, much of which exceeds my purposes here. But what we can see happening through Moll’s narrative, one in which she pulls herself up by her own (as well as others’) bootstraps, is that work becomes connected to personal, social, and economic improvement rather than being strictly an answer to a vocational call. (Interestingly, there is a moment in the story when Moll hears the audible call of one of her several [serial] husbands calling for her to return to him, and she does.) Defoe, it is relevant to note, was a Puritan (specifically, a Presbyterian) who held a number of political and business positions as he struggled throughout his life (sometimes unsuccessfully) to keep himself out of debtors’ prison. Defoe’s life, along with his character, demonstrates the new and tremendous pressure and anxiety felt by the modern person who is not lucky enough to be born into position and wealth to make something of themselves. The struggle was real. Os Guinness warns in his classic book The Call that a culture unmoored from a sense of calling and built on unrestrained capitalism, like the one Defoe portrays in Moll Flanders, is destined toward hedonism. Such a world reduces work to merely a means of gaining more money and more possessions on the terms of the free market.

In reading literature like this, we can observe the concept of vocation changing in real time, slowly being replaced by the modern notion of upward mobility and the desire for its newly attainable economic advantage. The idea of having a calling slowly evolved from holding a spiritual office (whether in the church or family) into making a living and having worldly success. Moll Flanders reflects Guinness’s observation that over the course of the modern age the “original demand that each Christian should have a calling was boiled down to the demand that each citizen should have a job,” and eventually work itself “was made sacred.”

Sacralizing work, however, desacralized the sense of the Caller and thus calling. Now, like Moll, we have a long menu of terms we use to refer to work: job, career, gig, employment, position, post, appointment, and occupation, to name a few. Now, instead of calling, late modernity hands us options, choices, opportunities, advancements, promotions, demotions, lateral moves—and gives us constant change over stability.

We were created to work—just as our Creator works—and that work will be part of the new heaven and new earth.

Meanwhile, the word “vocation,” as Guinness points out, is often assigned to the categories of jobs taken by workers who undergo “vocational training” rather than go to college, the kind of work disdained by the socially elite and highly educated. Looking down on any kind of “good work” (a favorite phrase of my father), however, reflects a diminished or distorted view of vocation. A robust view of vocation values the gifts and skills that vary from person to person and celebrates the good use of those gifts and skills.

This impoverished view of vocation, as portrayed above in large sweeps, has occurred over several centuries. But within narrower pockets of time—over the span of each succeeding generation in recent decades—we can see smaller shifts that feel terribly dramatic from one generation to another.

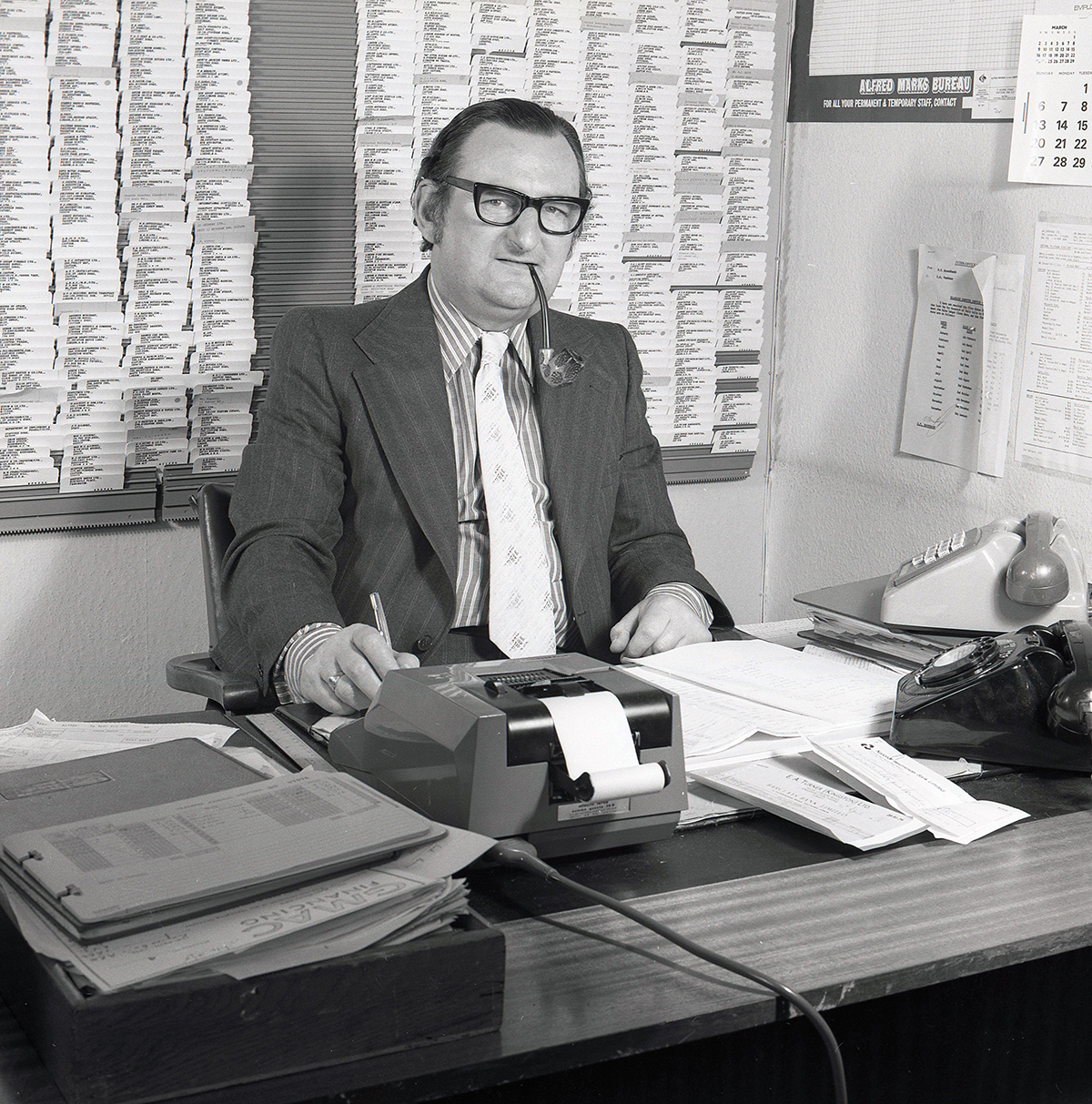

Members of the Silent Generation (born between 1928 and 1945) strived to work at one job or company for their entire career, earning a dependable salary, health insurance, a pension, and other benefits. Baby boomers and Gen Xers (that’s me) could hope for the same but might expect to move around in order to move up. But for millennials and those following them, that kind of continuity and certainty barely exists. In years past, I remember having to explain to some of my students looking for their first postgraduation jobs that “full- time” refers not just to a certain number of hours worked per week but also to the benefits that usually (or used to) come with such a position. But those conversations occurred in a context in which that option was more available. Now, just a few years later, we live in what is often called the gig economy, one in which more and more people (including me) are cobbling together various combinations of temporary and part- time jobs in order to make a living.

Within each of these contexts, work itself takes on a different character. Work shifted from being a means of supporting oneself and one’s family to being not only that but also a vehicle of greater personal fulfillment and eventually a means for fulfilling one’s passion. …

The autoworker of the past who clocked in daily and collected a weekly paycheck may have found his primary calling not in his work but in providing for his family, in having camaraderie with coworkers with whom he could share a beer in the neighborhood bar after work, and in simply being a part of his community. But in subsequent generations, particularly for those who invested significant time and money into going to college in order to obtain career success, finding one’s primary calling in work has become a general expectation.

In recent years, however, as a result of spiraling tuition and cost of living, many college graduates have found such an expectation difficult, if not impossible, to fulfill. The more one’s employment is linked to one’s calling, the more likely it is that jobs that don’t meet that criterion will be viewed as stepping stones to the ideal job, and the more likely it is that people will move jobs over the course of their working lives. As Guinness points out, the “increase in choice and change” that characterizes modern life “leads to a decrease in commitment and continuity.” ...

While we must work—just as human beings in all times and places have had to do—we in the modern age possess, along with more choices than our forebears generally had, a greater sense of burden and responsibility in making those choices. Within such a context, a job isn’t just a source of income but can be seen as a way to fulfill a greater purpose.

A general greater purpose, however, may not be (or at least may not feel like) your own greater purpose. Sometimes a person steps into a role not because it is the role they have long dreamed of but simply because they are particularly equipped and able to fill a particular need at a particular time. Finding work that aligns with our passions, desires, and gifts is, of course, ideal. It just doesn’t always happen, and that is okay. It doesn’t mean there is something wrong with you. Somehow we’ve gotten to a place in our world where people think there is something wrong with them when that alignment doesn’t happen or doesn’t happen right away. I always get comfort and a chuckle when I see the “Venn diagram of my life” meme. It shows three circles labeled “Things I like to do,” “Things I’m good at,” and “Things that make money.” Only the first two slightly overlap. There is no overlap with “Things that make money.” This meme, like so many others, exists to remind us that we are not alone.

Calling transcends all these categories. Ultimately, we can trust that when we are called, the call will—eventually—come through. Sometimes it might require a few tries to make the connection. Sometimes the call gets dropped. Sometimes someone gets a wrong number. But if we keep working at it, we can trust that the call will come.

(This essay is an excerpt from the You Have a Calling: Finding Your Vocation in the True, Good, and Beautiful by Karen Swallow Prior, forthcoming from Brazos Press, a division of Baker Publishing Group, copyright 2025. Used by permission.)