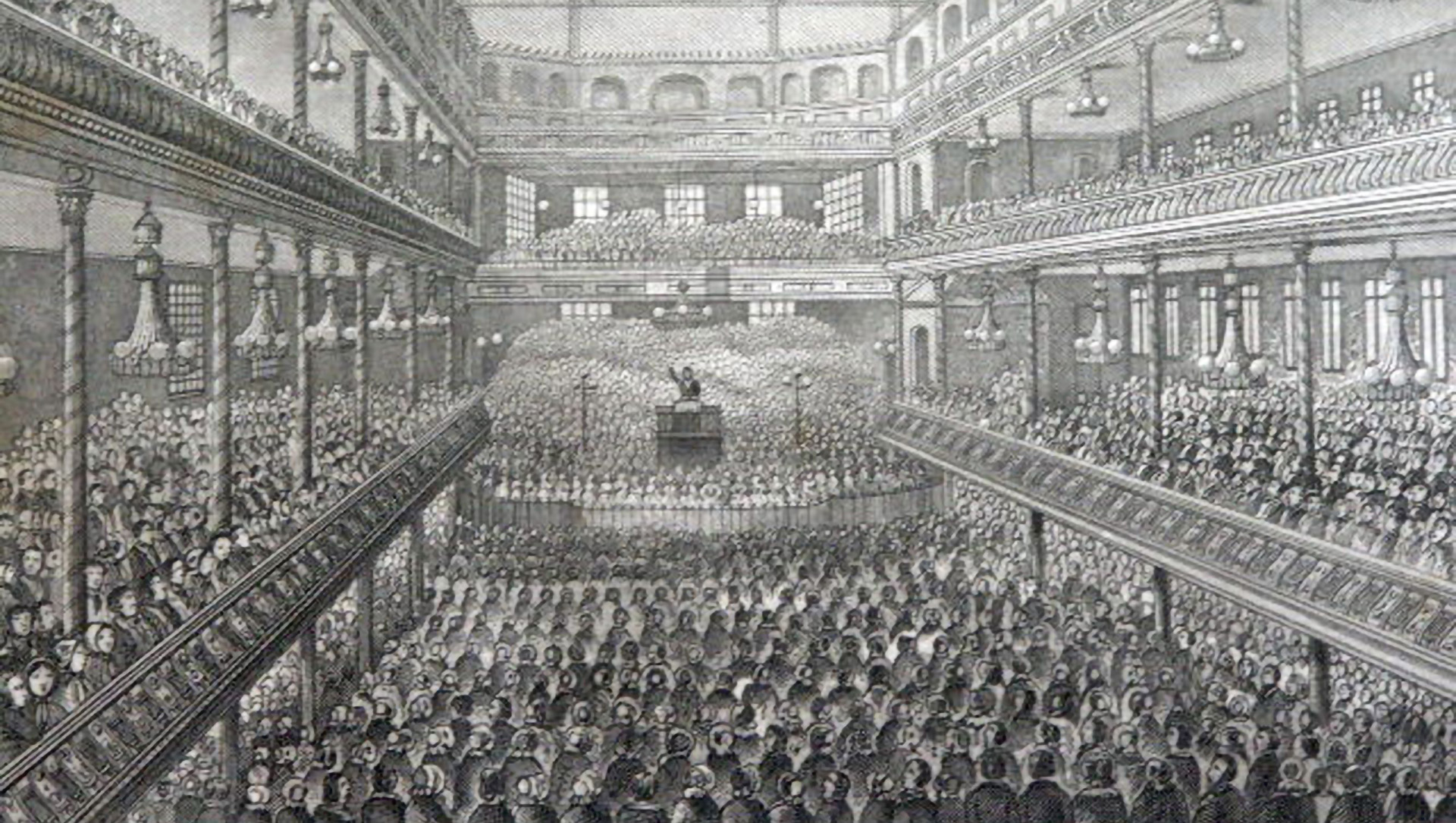

Alongside Luther, Calvin, and Edwards, Charles Spurgeon—the greatest preacher of Victorian London—is the Protestant icon most likely to appear on seminary syllabi and in conference sessions, as well as on T-shirts and coffee mugs. Spurgeon’s popularity is understandable when one considers the remarkable success of his 40-year ministry at the historic Baptist church that would become the Metropolitan Tabernacle. He regularly preached to crowds of 6,000 people, trained over 20% of British Baptist pastors, oversaw 66 social ministries through the church, and published more words in the English language than any other author.

The life of Baptist pastor and preacher Charles Spurgeon is a testament to what one humble man can accomplish in a great city under God’s providential care.

By Alex DiPrima

(Reformation Heritage Books, 2024)

In many ways, Spurgeon was a pastoral innovator, preaching energetically and renting large secular venues when his congregation outgrew its buildings. The masses, however, did not flock to Spurgeon just to be entertained. Londoners from all classes were drawn in by his eloquent yet populist sermons and strong commitment to the Reformed theology of his Puritan predecessors. His convictions came at great cost at many points during his ministry. His conflicts with Anglo-Catholicism and theological liberalism severed ecumenical ties at home. Further, his commitment to the abolition of slavery ended the sale of his published sermons in the American South, endangering benevolent institutions such as his Pastor’s College. Taking his character into consideration, it is no wonder that so many young pastors look to him as a model for convictional preaching in an attractional age.

Spurgeon’s growing popularity among reformed Protestants has been accompanied by great advances in research as well, particularly at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary’s ornate Spurgeon Library. Given this wealth of new scholarship—including the discovery of hundreds of lost sermons—an updated one-volume biography of the “prince of preachers” was sorely needed, and that is what Alex DiPrima has provided with Spurgeon: A Life. The book is a work of both history and historical theology, concisely summarizing the events of Spurgeon’s life and placing them alongside the theological motivations for his preaching, church initiatives, and dozens of ministries.

Given the volume of material by and about Spurgeon, a one-volume biography is a difficult task, yet DiPrima’s well-organized narrative accomplishes his goals of exploring Spurgeon’s theological convictions and making applications for his readers. In this focus, it is the type of biography that Spurgeon himself would have liked. DiPrima pauses his chronology with sections on significant institutions that Spurgeon led—such as the Tabernacle, the Pastor’s College, and the Stockwell Orphanage—and themes such as his loving marriage to Susannah, theological polemics, and response to harsh criticism. Through all parts of Spurgeon’s life, DiPrima draws explicit lessons intended to help his readers grow in their faith.

Spurgeon was not merely a preacher-in-chief or a CEO—he was a shepherd concerned with the spiritual state of his flock.

DiPrima writes with a background of extensive research (this is his second book on Spurgeon), but this biography is not primarily intended to contribute to an academic discussion. He writes as the senior pastor of a Baptist church that has a theology and philosophy of ministry that strongly resembles Spurgeon’s own. His stated intent is to write “for the church,” teaching members of congregations like his own about Spurgeon’s life and holding him up as an example of faithfulness. DiPrima argues that Spurgeon, through God’s special providence, employed his extraordinary faculty for preaching the gospel through his church and ministries.

DiPrima’s evaluation of Spurgeon’s significance is also unambiguous: He “occupies a unique place among ministers of the gospel.” Among the reasons he identifies for Spurgeon’s success is his striking giftedness in the pulpit from a young age. Saved at age 15 in rural East Anglia, he gained such renown for his preaching—earning the title “boy preacher of the Fens”—that he was called to one of London’s most historic Baptist congregations four years later. His classical boarding school education gave him a background in literature and rhetoric that informed colorful illustrations and applications that could appeal to an audience of mixed classes.

DiPrima also presents a compelling case that Spurgeon was uniquely suited as the self-described “forefront of Nonconformity” in Victorian London. While England’s Christian culture was declining, Spurgeon’s preaching was able to appeal to and strengthen it. An industrializing London was bursting at the seams with the lower and middle classes, and Spurgeon’s articulation of the Scripture was “frankly, earnestly, and lovingly” suited to them. Gertrude Himmelfarb has identified an evangelical ethic that was foundational for Victorian moral reformation, and Spurgeon’s posture toward ministry in London reflects this influence. He was never fully comfortable in the metropolis—much preferring the countryside of his youth—but he attacked social ills with an institutional approach aimed at caring for the underserved, as DiPrima details in his first book, Spurgeon and the Poor, which I reviewed in these pages.

In addition to pastoral care for the suffering, such as during the cholera epidemic of 1854, Spurgeon founded numerous ministries under the auspices of the Tabernacle. Two were closest to his heart: the internationally renowned Stockwell Orphanage and the Pastor’s College. The latter provided free theological education to those aspiring to the office of pastor, particularly ensuring that men from the working classes could reach their own communities. As DiPrima identifies, Spurgeon’s institutions enabled him to tie his evangelistic and social ministries together. As he said of the importance of spreading the gospel while serving physical needs, “The more our hearts beat in unison with the masses, the more likely will they be to receive the gospel kindly from our lips.”

Spurgeon’s ministry was thus congregational. His primary motivation for building a sanctuary that could accommodate over 5,000 people was to enable his entire congregation of church members to worship together at one time. He was not merely a preacher-in-chief or a CEO; he was a shepherd concerned with the spiritual state of his flock. This desire also informed his eventual adoption of a plurality of elders within the Tabernacle who could provide pastoral care to all members.

DiPrima depicts Spurgeon as a reluctant polemicist, only engaging in doctrinal debate when orthodoxy was endangered. His two great controversies exhausted him. Passionate sermons combating the sacramental theology of the Oxford Movement instigated his withdrawal from the Evangelical Alliance, and he left the Baptist Union for its failure to discipline overt heretics. He considered both Anglo-Catholics and liberals to be in serious error, for their claims struck at the heart of the Protestant gospel of justification by faith alone. Anglo-Catholicism in particular was so dangerous that he deliberately designed the Tabernacle’s new building south of the Thames in Elephant & Castle in a neoclassical style to rival the gothic mood.

Spurgeon was the opposite of reluctant when speaking about another great opponent: the evils of slavery. His greatest disdain was for complacent clergymen who tolerated it because of its apparent inevitability. As he said in a special worship service dedicated to abolition in 1859, slavery was indeed a “peculiar institution” because it is a perversion of the created order, denying the dignity and worth of “the least of these” for whom Spurgeon cared so deeply. Like Alexis de Tocqueville, he made dark predictions for the future of a nation that tolerated slavery, saying, “America is in many respects a glorious country, but it may be necessary to teach her some wholesome lessons at the point of a bayonet—to carve freedom into her with a bowie knife or send it home to her heart with a revolver.” His strident stance lost him many supporters in the American South, where his sermons were no longer published—even outlawed in some states—and his books burned.

For DiPrima, however, Spurgeon’s great talents and concern for Victorian London are only secondary causes of his success. The primary reason for his fruitful ministry was God’s providential care throughout his life. Writing to an audience of fellow Christians, DiPrima directly attributes many events—both ministry successes and hardships—to God’s sovereign hand. Preaching was his instrument to convert the young Spurgeon, as he used Spurgeon’s preaching to convert many others. “Any explanation for the extraordinary success of Spurgeon’s preaching that does not include this most crucial element will be wide of the mark. Spurgeon was mighty in preaching because God’s hand was on him in an awesome and mysterious way.” Later, DiPrima evaluates the great criticism leveled at Spurgeon’s pastoral innovations as a means by which God sanctified him, preparing him for greater work in the future.

Spurgeon’s commitment to the abolition of slavery ended the sale of his published sermons in the American South.

How can the Christian historian identify God’s providence in particular events of church history without descending into fallible speculation? DiPrima’s account is faithful to history, not speaking where God has not spoken, while reminding his readers of God’s sovereignty in saving sinners and enabling the work of ministry. Writing to the church, DiPrima correctly identifies God’s sovereign grace in bringing Spurgeon to himself, and he is right to affirm God’s work in saving others through Spurgeon’s preaching.

Further, DiPrima’s perspective reflects Spurgeon’s own trust in divine providence, both giving God credit for ministry success and looking to him for hope in times of trial. One of those moments came in October 1856, when Spurgeon broke pastoral norms by hosting a worship service in the Surrey Gardens Music Hall, intended to be a temporary home for his growing congregation of thousands. A false alarm of “Fire” caused a stampede, killing seven. Days of deep depression (and a lifetime of panic attacks and fear of crowds) ensued, but Spurgeon found solace in his Savior, whom he simply described later as “bringing back my soul to its own right and happy state.” Two months later, the church would return to Surrey Gardens, where services were held for the next three years.

Adding to his depression were Spurgeon’s physical challenges, including both Bright’s disease and rheumatic gout, which caused him immense pain and forced him to take annual retreats to the French Riviera to recover. DiPrima suggests that we view his suffering as both great and meaningful. Spurgeon was uncommonly transparent for his day with the public about his physical and mental condition, an example in his own day and in ours of confidence in the care of a God who sustains our Christian service.

Spurgeon: A Life is a welcome contribution to a growing body of literature, and it is a fitting pair with DiPrima’s 2023 study of Spurgeon’s social ministries. Both books rightly emphasize what Spurgeon emphasized: Christian care for the common good must be founded upon the preaching of the gospel of salvation through Christ.

Today, most pastors would not be entrusted with a major metropolitan pulpit at the age of 19, but they will likely face similar challenges: urbanization, suffering people, broken families, and a world (and sometimes a church) hostile to the Christian faith in word and deed. If they are church planters, they have likely been urged to give their greatest attention to “contextualization,” presenting Christian truth with a sensitivity to cultural barriers to the gospel. Spurgeon’s ministry to an estimated 10 million Victorians spoke to their spiritual and physical concerns. It also made no apology for the only solution to those concerns: the hope of the gospel and fidelity to Scripture and historic Christian orthodoxy. Pastors who, like Spurgeon, face a challenging world can also—through God’s grace—adopt a similar response: fidelity to marriage and the family, convictional preaching that points the world to Christ, and institution-building through which Christians can promote the basic goods of human flourishing. Those seeking “to do something for Christ” would do well to follow Spurgeon’s tireless example.