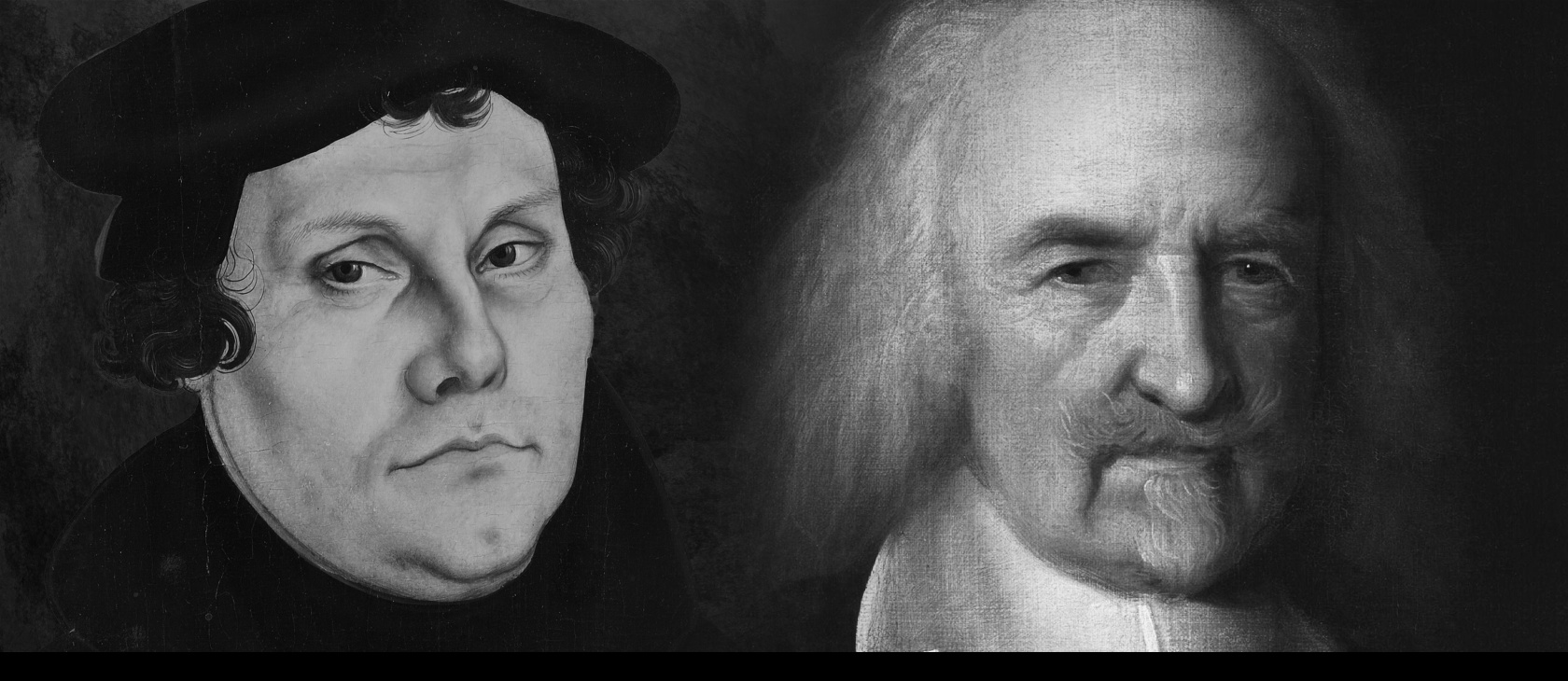

Thomas Hobbes and Martin Luther are two of the most influential thinkers in the development of the early modern world. While neither figure is a liberal in the proper sense (it is Locke who provides the first fully formed liberal conception of the state and its duties), they each provide some of liberalism’s core ideas. Luther’s contributions include the prioritization of the freedom of conscience, limitations on both church and state power, and a stronger sense of national identity. Hobbes introduces the state of nature, the social contract, and the centrality of rights.

Was the political theorist who insisted that life in a “state of nature” would be “nasty, poor, solitary, brutish, and short” a Lutheran? How about a Calvinist? An atheist? It’s … complicated.

Despite the impact of these two thinkers and some minor similarities, there are significant areas of divergence between them. Thomas Hobbes was a philosophical materialist, contending that God himself was a material being. Further, he had a dogmatically minimalist view of Christianity and believed that whatever doctrine was to be received should be decided by the magistrate rather than the church. Martin Luther, despite portrayals of him as a radical with purely novel ideas, retained classical Christian commitments regarding the nature of God, the immateriality of the soul, and the need for strong doctrinal confession. Apart from some shared objects of distaste—namely Aristotle and the papacy—the two ideological systems could hardly be more different. And yet Hobbes refers to himself as a Lutheran. But was he?

To answer this question, three others must also be addressed. First, what was Hobbes’ relationship to Christianity as a whole? While over a third of his writing addresses religious subjects, Hobbes’ identification as a Christian, or even as a theist, has often been questioned. Second, what does Hobbes mean when he uses the “Lutheran” label to identify himself? Third, in what way does Hobbes view Luther as a precursor to his own work?

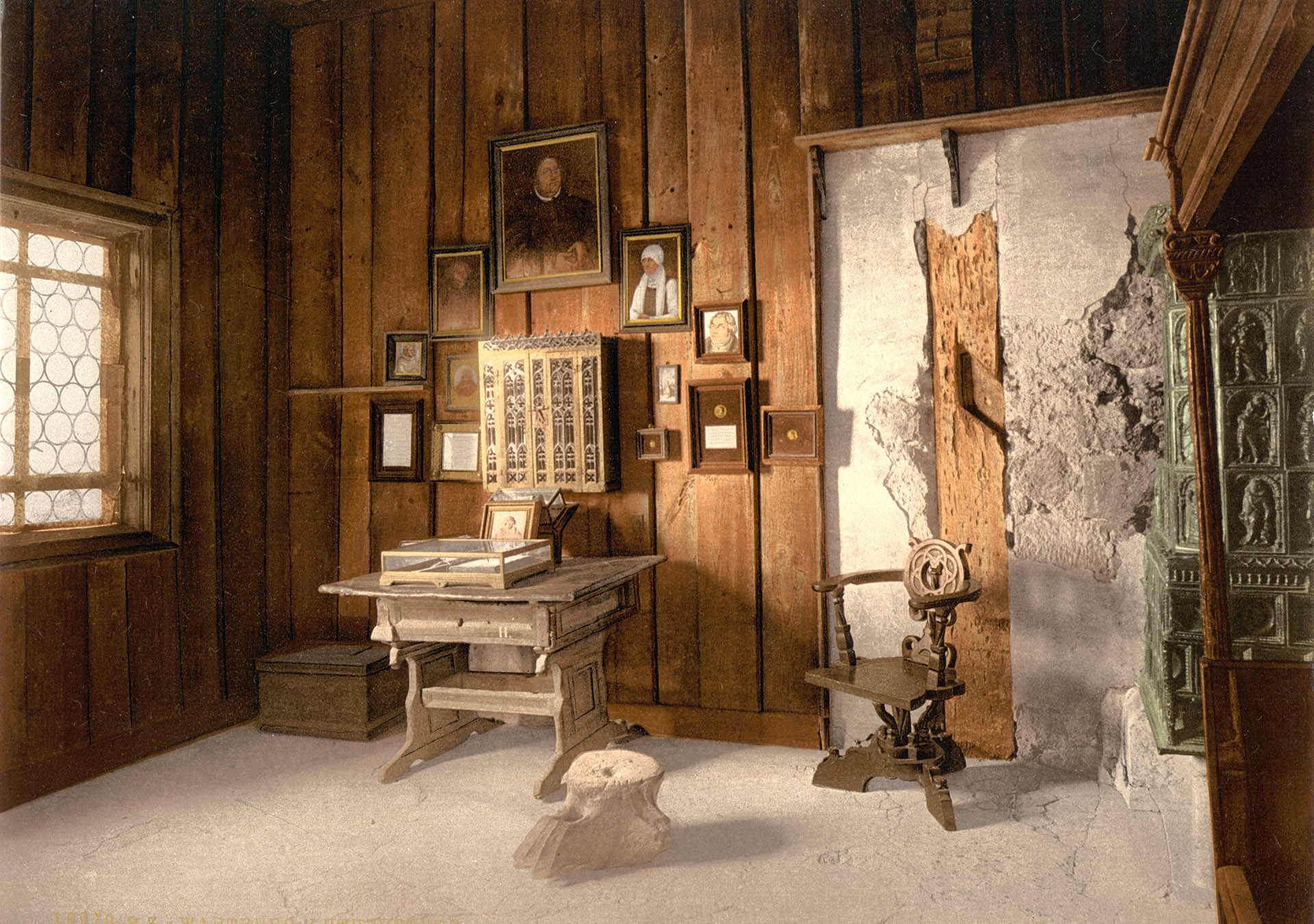

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) was born in Wiltshire, England. His father was a Church of England vicar who was removed from his position after getting involved in a physical altercation outside his parish. Following this incident, Hobbes lived for a time with a wealthy uncle who funded his nephew’s education. Hobbes was educated first at the Malmesbury School, and then studied at both Oxford and St. John’s College, Cambridge. Hobbes spent much of his career as the tutor to various members of the Cavendish noble family. Throughout his adult life, Hobbes wrote several books on a wide variety of subjects, including ancient history, biology, theology, and politics. While Hobbes had some influence in philosophy and the sciences, his longest-lasting contributions are in the field of political thought.

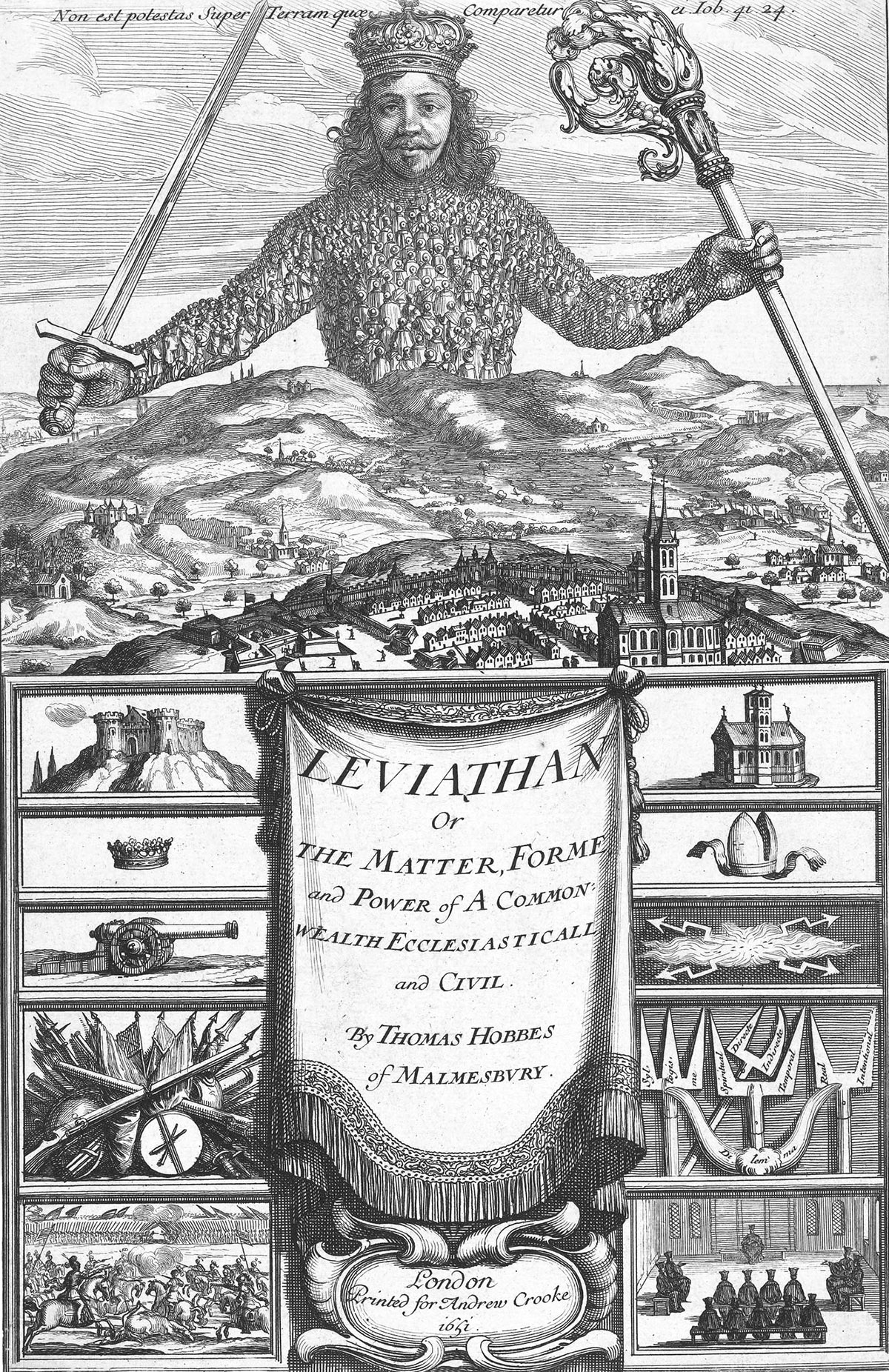

Hobbes’ political philosophy is covered most extensively in two works: De Cive (1642) and Leviathan (1651). The former was part of a broader project of three volumes in which Hobbes sought to set forth a comprehensive philosophy covering far more than political theory. The latter is his most influential book and remains a standard text in many political science and political philosophy curricula. In fact, the influence of Hobbes’ Leviathan in the history of political thought is nothing less than monumental. Diverging from earlier political writings, this work grounds its argument in the consideration of a theoretical “state of nature” in which men and women supposedly lived prior to the establishment of civil society. Government, for Hobbes, is not directly imposed by God but arises from mutual agreement by means of a social contract arising from this state of nature. Through this agreement, authority is delegated to an individual who is now the sovereign, and the commonwealth is created.

Thomas Hobbes’ relationship with Christianity has been a point of debate since the release of his first published works. Some contemporaries of Hobbes were concerned that his doctrinal perspectives represented a serious departure from Christian orthodoxy (in both its Protestant and Roman Catholic varieties). He was regularly charged with atheism, impiety, and heresy. Though Hobbes did defend some sense of continuity between his ideas and other preceding Protestant theologians, it is uncontested that his views were incommensurate with those of his Protestant orthodox contemporaries. During this era, Protestant theologians—both Lutheran and Reformed—preferred to use the scholastic method, which included a heavy use of Aristotelian philosophy. Hobbes rejected the Aristotelian system in its entirety, dismissing many of the metaphysical and philosophical commitments that Christian-Aristotelian synthesizers like Thomas Aquinas relied upon. Hobbes, for example, rejected the doctrine of divine simplicity (that God is not composed of parts), along with the immateriality of God and of the soul. For him, God is corporeal.

Despite these areas of departure from classical orthodoxy, Hobbes did view himself as a Christian. The question is exactly what that meant for Hobbes. In a statement summarizing Hobbes’ theology, Shirley Letwin, in “Hobbes and Christianity,” notes that, in his theological reconstruction of his faith, “Hobbes did nothing less than deny all the most cherished beliefs of the Christian world.” This departure from orthodoxy does not mean, however, that Hobbes denied Christianity as such. Instead, Hobbes believed that much Christian thought had been wrongly tied to an antimony of spirit and matter. In anticipation of what would later come to be known as the “Hellenization thesis,” Hobbes argued that early and medieval Christians adopted pagan conceptions of the Greek philosophers that privileged the immaterial over the material. Nearly all Hobbes’ doctrinal particularities arose from an attempt to de-Hellenize theology by getting rid of this supposed superiority of the nonmaterial, including his belief that spirits are made of matter.

What then is to be said of those who argue that Hobbes was nevertheless an atheist? This appraisal of Hobbes is not an uncommon one; it has found proponents as influential as Edmund Burke and Leo Strauss (The Political Philosophy of Hobbes). In this reading, Hobbes’ role in intellectual history was to desacralize the political. He introduced secularity into political discourse, removing theological considerations from the construction of law and placing governmental authority within a man-made social contract rather than divine appointment. This was all done, in this reading, because Hobbes denied the reality of the theological and sought to marginalize such considerations. And yet, if this is true, why did Hobbes write so extensively on theological topics? Willis B. Glover, in “God and Thomas Hobbes,” provides an overview of the three answers typically given by those who insist on reading Hobbes as atheistic. First, Hobbes wanted to destroy the veracity of Christian proclamation through a reductio ad absurdum. Second, he included appeals to God to protect himself from persecution. Third, appealing to religious argumentation would more strongly convince his readers, even though he himself did not believe in such things.

All these arguments, however, are difficult to sustain in light of the textual evidence. If Hobbes was appealing to religious authority for purely pragmatic purposes, there is no reason why he needed to do so as often as he did. It was precisely these appeals that led him into controversy, as the statements he did make on doctrinal issues were nearly always in defense of some departure from classical orthodoxy. This is hardly a sensible thing to do for someone attempting to avoid persecution or convince religious believers. Furthermore, if Hobbes really intended to divorce religion from the state, there were plenty of other ways to do it. A reworking of Luther’s Two Kingdoms doctrine, or of Augustine’s Two Cities, could have led to a sharp distinction between church and state in which theological matters are irrelevant to civic affairs. One of Hobbes’ most significant influences, Hugo Grotius, did exactly this by arguing for a state governed by pure reason rather than theology. Hobbes quite intentionally avoided this route not only by discussing religious ideas in his political philosophy but by making them central to it. (For more on this, see Michael Oakeshott’s Hobbes on Civil Association.)

It is most reasonable simply to take Hobbes at his word that he was a theist and believed that a unified religious commitment was necessary for the proper functioning of a commonwealth. From Hobbes’ perspective, theological doctrines are important but not to be decided by individuals. This would lead only to endless dogmatic battles between divergent denominational strains. Instead, religious beliefs are to be determined by the sovereign alone. One might contend in response that the total surrender of intellectual will to the sovereign on doctrinal matters is foolish if salvation and damnation are partially determined by one’s adherence to right doctrine. Why follow the sovereign’s theology if it might be damnable? Hobbes would no doubt respond by arguing that the only kind of doctrinal assent necessary for salvation is the affirmation that Jesus is the Christ. Therefore, so long as one confesses Jesus as messiah, there need be no worries about whatever other religious ideas are determined by the sovereign.

Thomas Hobbes was a philosophical materialist, contending that God himself was a material being.

It is important to qualify here that the necessity of obedience to the sovereign in such matters is not absolute, as is evidenced by the fact that, in De Cive, Hobbes contends that if a Christian lived in a pagan society, there would be no obligation to confess dogmatic paganism. Rather than revolt against such an authority, however, Hobbes insists that the Christian should always be ready for martyrdom for his or her confession of the Lordship of Christ. Yet his perspective had changed by the time he wrote Leviathan. In this later text, Hobbes argues that the Christian must resist paganism internally but can still confess paganism externally in obedience to the sovereign. The only case in which confession of Christianity is necessary, even when suppressed by the sovereign, is that of Christian clergy, who should always be prepared for martyrdom.

To summarize: It is clear that Hobbes was not an atheist but believed himself to be a Christian. He argued that the state should affirm the messianic reign of Christ and that the sovereign is bound to enforce Christianity. Hobbes’ conception of Christianity, however, was minimalistic, and the dogmatic claims he did make were not within the bounds of general Christian orthodoxy. In view of Hobbes’ approach to Christianity generally, we now explore his view of Lutheranism specifically.

Most of Hobbes’ praise for Martin Luther addresses the Reformer’s historical significance as a precursor in fighting against abuses of clerical power. It is not generally the theological elements of Luther’s life or thought that are held in esteem but rather his arguments against the temporal authority wielded by the medieval papacy. Yet there is one place where Hobbes explicitly praises a doctrinal element of Luther’s writings. This is in Hobbes’ treatise The Questions Concerning Liberty, Necessity, and Chance, written in 1656.

The occasion for this treatise was the work of another author, John Bramhall, who had questioned Hobbes’ Christian orthodoxy and piety. Bramhall was a member of the Anglican clergy who, like Hobbes at the time, was an English refugee who temporarily resided in France—both had fled due to the fear of an impending civil war. He and Hobbes had a mutual friend in the Marquess of Newcastle, who had invited the two men to debate the nature of necessity and causality in Paris (two points of controversy in Hobbes’ philosophical system). The debate, in brief, focused on the idea that all historical events happen of necessity. Hobbes’ view of the natural world was a purely physical, “mechanistic” one. In this perspective, biological entities act like machines, through which a series of necessary physical actions follow one another naturally. For Hobbes, this meant that, in biological creatures, there is no possibility of acting otherwise by means of a free will. If human beings are purely physical, with no free will or immaterial soul, then all human actions are performed of necessity. Humans could not possibly act otherwise than they do. This, for Bramhall, was a drastic departure from traditional Christian doctrine, as it essentially made God the author of sin. If God is the creator of humanity, and humans cannot choose to act other than they do, then God is the cause of all human actions—including evil acts.

Bramhall’s critiques of Hobbes’ position were published in his work A Defence of True Liberty from Ante-cedent and Extrinsecall Necessity, in 1655, which led to Hobbes’ response the following year. In his treatise, Hobbes adamantly opposes accusations of atheism, arguing that his approach to the necessity of all events and actions is simply a reiteration of ideas already present in a variety of Protestant texts. Hobbes insists that his doctrine of “necessity” was that of the Reformed churches. In defense of this alignment with Calvinism, Hobbes argues that philosophical necessity is an essential element of the Reformed doctrine of predestination, and that it was Bramhall, rather than he, who had departed from these Protestant convictions. Though Hobbes speaks of this doctrine as Reformed, rather than Lutheran, it is Martin Luther, not John Calvin, who is cited as his chief authority on the matter.

Hobbes’ reason for citing Luther, rather than a Reformed theologian is twofold. First, Hobbes already had a strong appreciation for Luther as a prophetic voice in opposition to the papacy. Second, an appeal to Luther made for a more universal argument than if Hobbes had cited one particular Reformed divine. As Hobbes reminds his readers, Luther’s work marks the beginning and source of the Reformation and its theology. All Protestant theology derives from him. In Hobbes’ argument, this idea of causal necessity is not the idiosyncrasy of one theologian but lies at the heart of Protestantism. In defending his “Lutheranism,” Hobbes defends his Protestantism, and his orthodoxy more generally.

From Hobbes' perspective, theological doctrines are important but not to be decided by individuals.

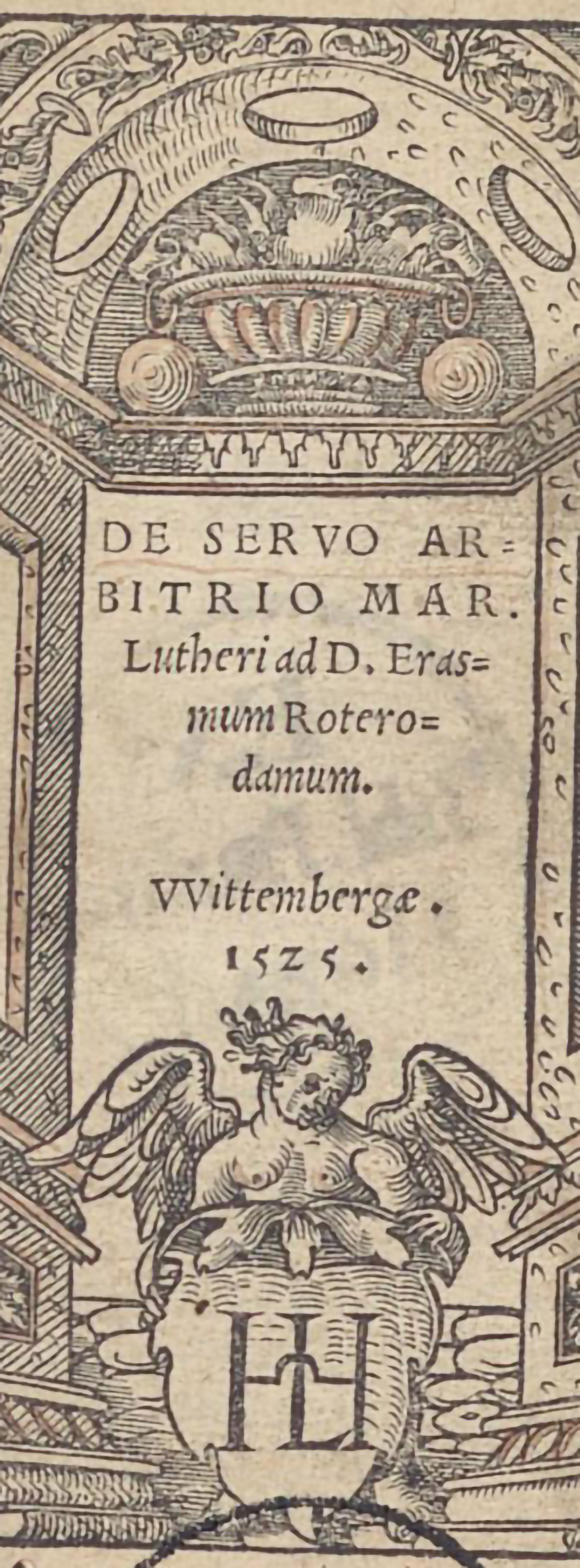

The argument Hobbes makes arises from Luther’s 1525 book De servo arbitrio (On the Bondage of the Will). Like Hobbes’ treatise, Luther’s work was also written as a response to a critic—the famed Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus. In this text, which Luther himself considered among his best, the German Reformer argues against the idea of spiritual freedom, contending that fallen humans are bound to sin. Luther uses bold phrases (as he was prone to do) like “all things happen of necessity” and “free will is a fiction.” Hobbes certainly has an argument to make here, as some of Luther’s statements are nearly identical to those he uses. Further, Hobbes employs a distinction from Luther’s text to show how necessity in human acts does not make God the cause of evil acts: that of compulsion and necessity. For Hobbes, all actions are necessary, but they are not all done through compulsion. In other words, God does not force creatures to act. Human beings really will to do various things in life, so that God does not force the movement of the human body against an individual’s will. The necessity by which creatures act is a necessity of immutability, rather than a necessity of constraint.

The question to be asked regarding Hobbes’ use of Luther is whether this really makes Hobbes a Lutheran in any meaningful sense. First, the designation “Lutheran” must be defined. There is a twofold sense in which this term is used. In its most common usage, a Lutheran is one who belongs to an ecclesiastical community identified by that name. These communities are churches that subscribe to the teachings of the Lutheran Confessions—most centrally the Augsburg Confession and Luther’s Small Catechism. In this sense, Hobbes is not a Lutheran, as he was not a member of a Lutheran church and nowhere expressed any kind of firm adherence to the theology contained in those documents. The second use of the term “Lutheran” is mere identification with the ideas of Martin Luther. It is in this regard that Hobbes might be considered “Lutheran” in some way.

And yet, it is questionable whether the label applies even in this sense, as the claimed connections between Luther’s theology and Hobbes’ philosophy are not nearly as clear as Hobbes indicates. It is significant that it is only after Hobbes is challenged for his orthodoxy that he makes these connections between his view of necessity and Luther’s doctrine of divine causality, making it appear more as justification after the fact rather than a driving force in the construction of Hobbes’ ideas. Further, even in his defense, Hobbes seems completely unconcerned with the theological or spiritual context of Luther’s doctrine. As Jürgen Overhoff observes:

Hobbes took no heed whatsoever of Luther’s spiritualism. Whereas the Reformer laid great emphasis on the fact that only the Spirit of God could necessitate the will of man to seek what was due for his salvation, Hobbes did not speak about the workings of the Spirit at all, contenting himself instead with the knowledge of the divine necessitation of all events by secondary causes. (“The Lutheranism of Thomas Hobbes”)

As Bramhall points out in his response to Hobbes’ treatise, Luther’s book is not a general treatment of causal necessity but a consideration of the effects of sin on the human will and on the necessity of grace in freeing the will and delivering faith to sinners. This is evidenced in the fact that the Augsburg Confession—which Luther praised and signed on to—distinguishes between freedom in things “below” and things “above,” contending that it is in things above (i.e., spiritual things) that the will is bound, rather than in ordinary earthly actions. Hobbes’ view of necessity, in contrast, is absolute.

There is no question that Luther influenced Hobbes and that Hobbes viewed himself as an heir to Luther in some sense. This should not be construed, however, as a statement of doctrinal or ideological agreement. Luther’s entire system was driven by his conception of the gospel, that the Son of God was crucified for the forgiveness of sinners, and that this grace is freely dispensed through word and sacrament to be received through faith alone. Even in his religious writings, these themes are not central to Hobbes, who is far more concerned with political sovereignty, biological determinism, and Christian materialism than the doctrine of justification sola gratia (by grace alone). Thus, whatever commonalities appear between the two thinkers, they are driven by almost entirely different concerns and questions, and thus are only superficially related. Rather than ideology, Hobbes’ deepest connection to Luther is his belief that the two are part of the same historical and political trajectory.

Hobbes’ rejection of some of the primary commitments of classical Christian orthodoxy demonstrates a strong sense of discontinuity between his work and earlier Christian history. He viewed himself as one figure in a process of emancipation from a series of mistakes made within both the church and civil society that led to the dominance of the medieval papacy. Hobbes believed that the political philosophy set forth in both De Cive and Leviathan would come to shape a greater order in Europe, in which authority was no longer placed in ecclesiastical leaders or individual consciences but in the dictates of the sovereign. In this emancipatory process, Hobbes believed that he was following the reforms of Martin Luther, who Hobbes refers to as “the beginner of our deliverance.”

For Hobbes, the history of the church after Pentecost was one of degradation prior to the advent of the Reformation. He contends that the “kingdom of God,” as expressed throughout the Gospels, is a literal and physical reality—an earthly instantiation of the reign of Christ within the Christian state. Without a Christian sovereign, the early church began to consolidate authority within itself, with the clerical class wrongly becoming arbiters of Christian truth. Consequently, ecclesiastical hierarchies demanded obedience to themselves rather than to political authorities. In Hobbes’ interpretation, the Christian message demands obedience to the magistrate rather than to priests or bishops. This message was lost in the Roman Empire and only gradually recovered after Luther’s reforms.

Hobbes refers to this process of consolidation as three “knots” that hindered the freedom of Christians. The first knot was that initial positioning of authority within the clergy rather than the magistrate. The second was the unification of ecclesial authority within one church body—resulting in the consolidation of power (eventually under the bishop of Rome). The third was the broadening of that authority throughout the entirety of the empire. While one might expect that Hobbes would praise Constantine as the kind of Christian magistrate he believes to be necessary, he does not, since Constantine ultimately granted dogmatic authority to the leaders of the church.

In Hobbes’ version of ecclesiastical history, Luther began to untie these knots by first challenging papal supremacy. In the medieval church, it was believed that the pope had two swords—one of temporal and one of spiritual authority. Luther argued that such power was not granted to the bishop of Rome. For Luther, there is a strong distinction between temporal and spiritual authority. Those who have been given a specific vocation within one of those realms must not encroach upon the other. In treatises like Address to the Nobility of the German Nation (1520), Luther called upon civic authorities to act in defiance of Rome for precisely this reason. Luther was, for Hobbes, only the beginning of this process, which continued in England. In England, all three of these knots had been untied, beginning with the English church breaking from Rome, and then proceeding with the Puritans challenging the authority of the Church of England, and finally with the consolidation of power within the monarchy, rather than the church. In this way, according to Hobbes, the Church of England had fulfilled the original calling given to the world through Christianity.

Hobbes’ view of the state is, like his view of necessity, only superficially related to Luther’s understanding of the civic estate. For Luther, both the state and the church have been granted legitimate divine authority and must exercise that authority properly within the specific realms over which they have been appointed. The state has authority over temporal and bodily matters, while the church exercises authority over spiritual and theological affairs. Luther’s critique of Rome’s abuses are often related to the papacy’s encroachment upon areas of temporal authority, which the church has not been granted. He is, however, equally critical of the notion that the magistrate has the right to determine dogma or administer the sacraments.

Hobbes, in contrast, argues for the consolidation of both spiritual and temporal authority under the sovereign. This is not Erastianism, in which the state may rule over the church. Instead, Hobbes identifies the state with the church. Not only does the sovereign determine church leadership and put legal boundaries around ecclesiastical activities; he determines doctrine, as he is lord over both civic and spiritual affairs. In stark contrast, Luther’s political writing is nearly always focused on the distinction between the spiritual and the temporal realms, along with identification of the proper delegation of authority between the church and the state. This central distinction is exactly what Hobbes denies.

How do we then answer the question posed at the beginning of this article: Was Hobbes a Lutheran? In brief, no. Hobbes had no allegiance to Luther’s dogmatic convictions other than a superficial relation between a materialist determinism and Luther’s doctrine of providence. He also stood firmly against Luther’s distinction between temporal and spiritual authorities, which is at the core of the Reformer’s political philosophy. It is only in the sense that Hobbes saw Luther as a pivotal figure in shifting Europe away from allegiance to ecclesiastical authorities that he views himself as an heir to the German theologian. While atheistic interpretations do not adequately account for the idiosyncratic beliefs of Thomas Hobbes, neither do interpretations that align him with Lutheranism or any other branch of orthodox Christianity. Hobbes remains what he has always been: unique.