Anglophone analytic legal philosophy has for decades been oriented around the work of H.L.A. Hart and Joseph Raz. According to Hart, law is based on social sources, particularly rules of recognition. However, it can be objected that social rules explain only how a law is validly created without justifying the obligatoriness of law, prompting Raz to explore law’s moral reasonableness. However, if the reasons for law are known and accepted by the citizen, then obligation is not to the law but to those reasons the citizen himself knows and applies. On either account, what is the authority of law, and is there any obligation to obey?

What makes a law law? Why do we obey? Why should we obey? It’s all about the end to which it’s put.

By Daniel Mark

(University of Notre Dame Press, 2024)

In The Nature of Law: Authority, Obligation, and the Common Good, Daniel Mark, associate professor of political science at Villanova University, ambitiously sets out to critique the misunderstandings of Hart, Raz, and their many influential students, arguing that the pervasiveness of their errors has distorted legal philosophy, especially when it comes to the question of law’s authority. Against them, Mark views law as “in between” their incomplete theories and defines law as command oriented to the common good.

In responding to the view of law as “order backed by threats” and other sanctions-based accounts, Hart adopts the internal point of view. People do not experience law as threat, or at least subjects within a given system of law do not, for they do not feel themselves obliged to obey, as one might feel obliged to comply with an armed kidnapper. Instead, subjects view their system as placing an obligation upon them, or as a morally edifying suggestion, or as a custom of what we habitually do around here. It is thus incumbent on Hart to account for the obligatoriness of law, and this, says Mark, he fails to do. Citizens do not obey because they feel obliged or forced, hence rules based in social practice inadequately account for obligation. Social rules describe the genesis of law—a majority of duly elected legislators vote and the governor signs, for example—and perhaps the rules by which laws are considered valid, but fails to explain why the citizen ought to view a formally valid law as authoritative. All we have is an origin story of legislation, but social practice cannot explain our duty to obey.

With Raz, we might take the view that good law is reasonable, but if reasonable it provides no new reasons for subjects to obey that they do not already possess and give to themselves. A citizen might be ignorant of a reason that the law teaches, but that pedagogical function merely informs the subject of a reason already applicable to them in principle. In that case, the law has no particular authority, or, to put it differently, the law has not provided a reason to obey the law solely because it is law. So, we have the dilemma of authority: If the law is justified because of its reasonable content, the law is not authoritative and there is no obligation to obey it as law. But, if the law is not justified due to its reasonableness, the law commands in a way that looks like coercion rather than obligation. In either event, law does not seem to have authority, and neither Hart or Raz can resolve this problem, or so argues Mark.

To resolve the dilemma, Mark claims that authority is content-independent but provides second-order reasons for action. As he sees it, authority need not be correct in every particular legislation and can require from subjects acts they do not themselves have reasons to do, or even have reasons not to do, so long as authority acts for the common good in general. Authority obligates without needing subjects’ agreement with the law, and, moreover, authority is justified even when this or that particular directive lacks justification. Authority is not authority if justified only when subjects already have reasons to do what the law promotes, in other words. Thus, for Mark, the law is authoritative on the condition of content independence—namely, there is an obligation to obey the law without justifying the content of each law.

Mark argues that the law, to be law, is a set of commands oriented to the common good.

In fleshing this out, he distinguishes between first- and second-order reasons for acting. A first-order reason promotes acting or not acting, such as when research indicates a stock’s price is relatively low to value and would result in a significant return—that serves as a reason to act, and a reason of the first-order. A second-order reason gives a reason to follow or ignore a first-order reason, such as if I have a principle never to invest without the advice and consent of my spouse. My research still suggests I have a good first-order reason to buy this particular stock, but my spouse is unpersuaded, and based on this second-order rule I do not purchase the stock. Consequently, law provides second-order reasons: Whatever I think of a particular law, there is a second-order reason preempting whatever justifications I have to obey or not obey it, and this second-order reason is content independent. I need not agree or understand the law, but that it is law, just as such, presents me with an obligation to obey.

At this point, Mark recognizes that, while his sense of law’s command entails our obligation, it’s unclear that law is justified command rather than an edict backed by threat. If we appeal to the content or reasons for law, we will defang it as authoritative; but if we provide no justification, it is merely coercion. Mark argues that the law, to be law, is a set of commands oriented to the common good, and it is the orientation to the common good that provides the needed justification, not for particular directives but for the authority of the entire system. The form of law is command, the content of law is its orientation to the common good, but the normative aspect of the common good requires the formal or descriptive sense of command so subjects know who possesses and exercises that directive authority. He indicates there might be laws that do not command, but command is the central case of law, for absent command there is no obligation or authority.

It seems to follow, and Mark affirms as much, that a particular unjust law retains its authority even though it “weighs down” the system and “potentially erodes its legitimacy.” Still, the central case considers the entire legal system’s orientation to the common good rather than a piecemeal review of each bit of legislation; if the system as a whole is justly oriented, there is a “prima facie obligation to obey even an unjust law.” At the same time, while there is an obligation to obey, the weight of obligation can vary in force and the obligation to obey this or that unjust law is diminished, even though an unjust law within a system oriented to the common good retains the force of law.

That an unjust law remains law will strike some as undesirable, and Mark astutely explains that his view is compatible with democracy and popular sovereignty while not requiring them, a claim many readers will find somewhat bracing. Nothing in his formulation requires democracy; in theory, a nondemocratic system of commands oriented to the common good would be a justifiable system of law. Still, while the justification for authority is based on the common good rather than consent, he notes significant limitations on governmental power and jurisdiction, including that the common good is best attained through limited government combined with private effort, or the classical understanding of subsidiarity. The common will does not trump the common good, but private decision is a vital aspect of advancing the common good. Any system that removed local or private decisions would find itself incapable of satisfying the common-good condition of Mark’s theory of law, and revolution or disobedience are potentially justified when a system loses or threatens the orientation to the common good on the whole.

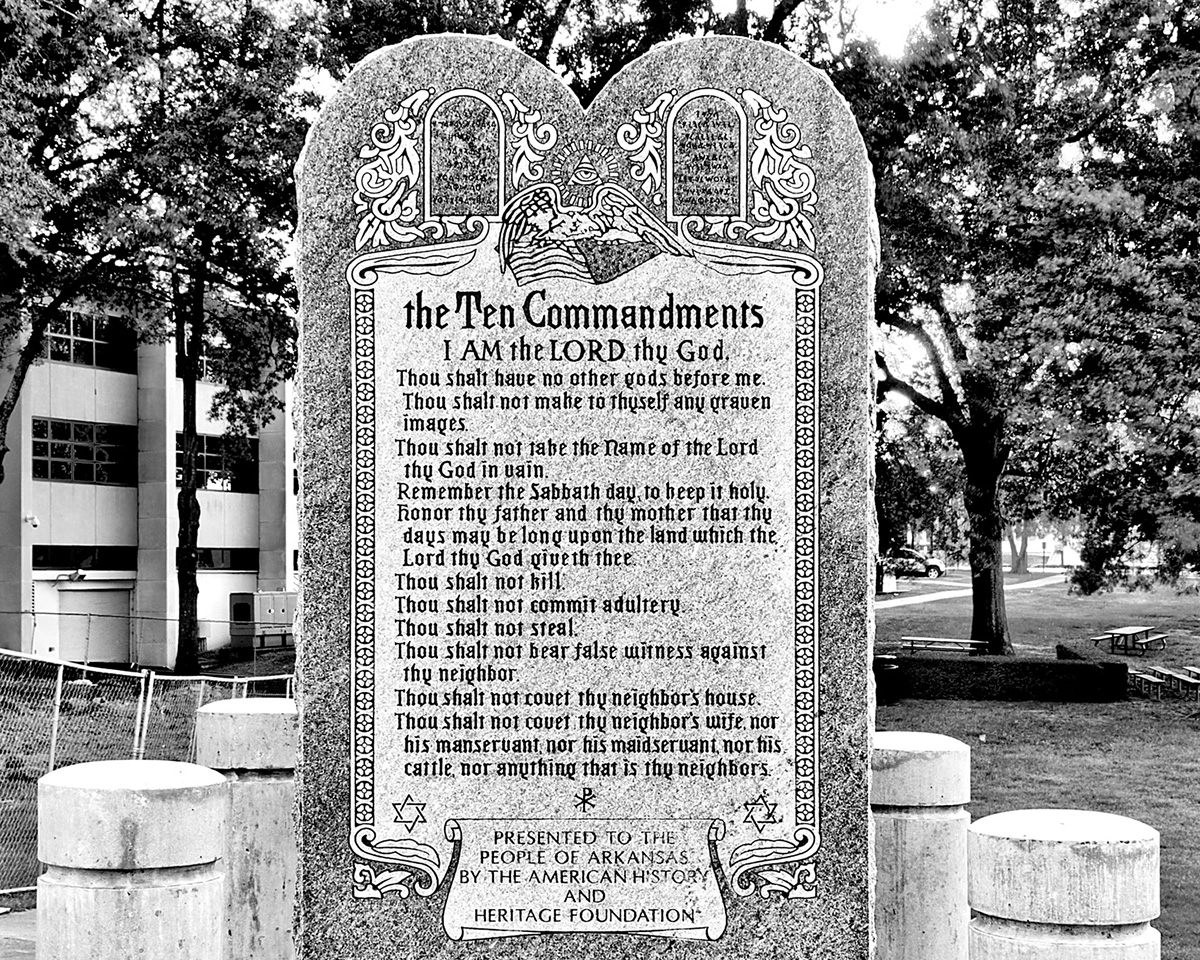

In a very interesting section, Mark argues that legal obligation is not reducible to either moral or religious obligation but combines elements of both. Moral obligation has authority, he says, exclusively from the reasons for those obligations, with no sense of command entailed. Religious obligation, conversely, stems from the authority of divine command, which is content independent. That is, even if the divine commands always serve the good, authority comes not from the goodness of the directive but solely because God is a commander. Like these two types, and unlike them, a system of human law can command our obedience without providing reasons for each particular law, even while the entire system is justified by reasonably serving the common good. Of course, one might object that the moral law does in fact command, either because God provided the law or that through morality we self-govern and command ourselves; conversely, divine command theory risks making God voluntaristic, even potentially capricious, although Mark denies those claims.

The Nature of Law is a technical book for specialists. It’s clear and well-written, but most people new to analytic jurisprudence will find it a challenging read. The effort is rewarded, however, for Mark provides an intriguing and intelligent proposal, one that prompts the reader’s hesitation, objection, argument, and reflection, which makes this a very good book indeed.