John Dickinson is the least known among the American founders. This is almost completely the fault of historians and students of political theory and constitutionalism, who have neglected him for over two centuries in favor of Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, et al. Yet the Pennsylvanian played an important intellectual role in every decisive moment of the long American Revolution, from the tax protests of the 1760s through the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788. Along the way he penned public essays that formed the basis of the constitutional argument against parliamentary taxation of the colonies, served as governor of both Pennsylvania and Delaware, was primary author of the Articles of Confederation, presided over the Annapolis Convention, and was one of the framers of the U.S. Constitution.

Ideas like “consent of the governed” and “no taxation without representation” are not products of the Enlightenment but instead have deep roots in Western Christian thought. One Founding Father made sure a new nation realized this part of its heritage.

M.E. Bradford says that Dickinson was “possibly the most learned of the framers.” And this was a very learned group. Yet the founder downplayed reason, theory, and populism as reliable sources for good government. “Experience must be our only guide,” Dickinson said. “Reason may mislead us.”

Dickinson first made his influence felt during opposition to the 1765 Stamp Act, a heavy-handed attempt by Parliament to extract revenue from the colonies, ostensibly to help defray the cost of their defense following the French and Indian War. The Stamp Act threatened to force Americans to buy government-issued stamps that would be affixed to nearly all printed documents, from contracts and licenses to newspapers, broadsides, and even playing cards. Only crown sterling, a rarity in the colonies, would be accepted in payment for the stamps. In violation of common law, offenders were to be tried before Vice Admiralty courts—military tribunals, where there would be no juries and the burden of proof would be on the accused to prove his innocence. This enraged Americans, who were accustomed to taxing and ruling themselves through mixed assemblies.

Dickinson called the Stamp Act unwise and illiberal, a threat to property, security, and happiness. One’s property could never be secure under a system where there was taxation without representation. Dickinson argued that protection of private property is part of the foundation required for the freedom necessary for human flourishing. Men could not be happy without freedom, he said, and they could not be free if they could be taxed without their consent. That one’s property could not be requisitioned or taken or taxed without consent through some form of representation had deep roots in Christian history (more on this later) and was foundational to English liberty.

Dickinson suggested that Americans merely ignore the Stamp Act, since only by force of arms could Britain hope to enforce it, and that was out of the realm of possibility. Jane E. Calvert, editor of the John Dickinson Papers, calls this “the first instance of the public advocacy of civil disobedience as a means for resisting government oppression.” She credits the family’s Quaker influence on Dickinson (who was not himself a Quaker) for this, as they had long resisted laws of religious oppression aimed specifically at them.

Prodded by William Pitt the Elder and Edmund Burke, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. Like Dickinson, Pitt and Burke opposed the Stamp Act not only on constitutional grounds but also in terms of political prudence, historical precedent, and the impracticality of ruling Americans from thousands of miles away.

Not one cent was ever collected from the American colonies under the Stamp Act. The whole affair, however, alerted British subjects on both sides of the Atlantic that a previously unknown gulf existed between them. That gulf would grow wider two years later with the onset of the Townshend Duties, Parliament’s second great attempt to tax the Americans contrary to common law traditions and the long experience of British North America.

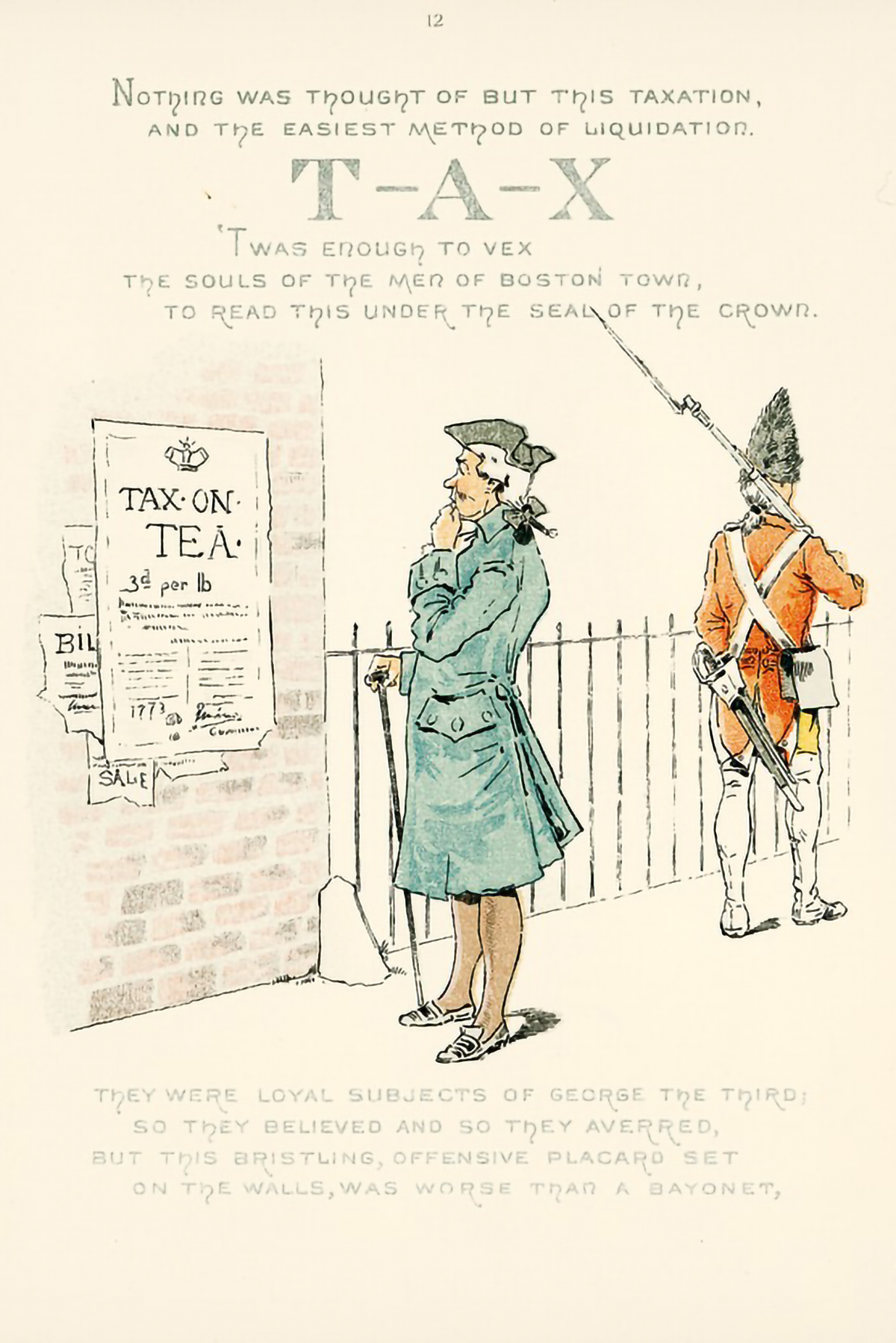

The Townshend Duties, a result of crony capitalism and parliamentary corruption meant to prop up the British East India Tea Company, were taxes to be placed on everything from glass and paper to tea and lead. Goods would not be allowed to be exported from North America before first passing through British ports. A major goal of the duties was revenue, which would be used to pay salaries for royal governors and justices, making them unaccountable to the Americans and beholden only to the Crown. In the face of immediate opposition, including a boycott of all British goods, Britain sent regular army troops into Boston to quell any disturbances.

Dickinson may have been influential at the Stamp Act Congress but it was his Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania protesting the Townshend Duties that made him famous. Dickinson was concerned most about violations of English common law and how these might provoke “hot, rash,” and “disorderly proceedings.” A riotous American response, he feared, would harm the cause of liberty more than help it.

In Dickinson’s mind, the problem was that the taxes were designed to do the unprecedented: extract revenue from the colonies. By violating the tradition of local governance, the “alarming” prospect was less the level of taxation than that the act would “establish a precedent for future use.” The tax rate would actually be low, but Dickinson recognized that this made the law more dangerous, because he feared Americans would be less likely to protest. Thus, precedent could be easily established that would result in future abuse. This in turn meant that private property, so necessary for liberty, would be subject to arbitrary confiscation. Such dangerous power in Britain would be “utterly destructive to liberty here.”

Dickinson saw the Townshend Duties not as an inflammatory moment of opportunity presenting a good excuse to hold a rebellion, but rather as a misguided violation of constitutional tradition. The American response, he thought, should therefore be a balance of loyalty to the Crown combined with an historical and common law argument.

He applied prudence and temperance in a balancing act to defend American and English traditions—which he saw as invariably a single tradition—in the face of Parliament’s “dangerous innovation” on one side and hotheaded Americans itching for a fight on the other. Thus, he went out of his way to reject revolutionary ideas and rebellious actions, instead highlighting the long tradition by which Americans and English had benefited. “The national objects” of the whole English project of having American colonies had been to make “for their mother country those things which she did not produce herself; and by supplying themselves from her with things they wanted.” Because trade and freedom are intricately linked, to achieve “these grand purposes, perfect liberty was known to be necessary.” And so generations of colonists had braved “unknown climates and unexplored wilderness,” freely taking on all the risk while England benefited. Despite mercantilist trade restrictions, Americans benefited as well.

The resentment and boycott fueled events that culminated in the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, when British regulars fired on a mob of Boston civilians, killing five. In the wake of the riot, the British pulled out their troops. Parliament soon repealed all the Townshend Duties, except for the one on tea. In 1773 the Tea Act lowered the tea duty by 300%, with the clear implication that Americans were not principled in their opposition to the Townshend Duties. Given the chance to buy East India Tea Company tea at lower prices than smuggled tea, Parliament expected Americans to opt for pocketbook over principle. This presumption of American vice, reducing as it did all American constitutional and moral arguments to a dishonorable love of money, enraged Americans. The response in Boston was the Tea Party on December 16, 1773, when Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty dumped a cargo of valuable East India Tea Company tea into the harbor.

The best place to look for the role of principle over an alleged love of mammon in the American Revolution is in this protest of the tea act. Outside modern progressives, there are few who would so vigorously protest the lowering of their taxes by 300%.

John Adams, admired as the great American conservative of this period by Russell Kirk, effusively praised the event. For Dickinson, however, this was exactly the kind of imprudent and immoderate act he had feared. Dickinson had stirred men to action with his words since 1765 but opposed wholly and completely what historian and Dickinson biographer William Murchison calls Samuel Adams’ “fury for confrontation.” In this, Dickinson was more like the Virginian George Washington. Washington agreed with what he called the “cause” of the Bostonians but, like Dickinson, criticized the destruction of the tea, which he thought struck too strongly at the sanctity of property. Riots are not the politics of prudence.

Parliament’s response to the Boston Tea Party was to revoke Massachusetts’ colonial charter and pass other legislation meant to punish the citizens of Massachusetts by coercing them into paying for the tea destroyed by Samuel Adams and his men. These acts ignored the injustice of punishing all for the actions of a few, and each of these “coercive acts” (called “intolerable acts” by the Americans) in their own way violated common law, the colonial charter of Massachusetts, and private property rights.

In Dickinson's mind, the problem was that the taxes were designed to do the unprecedented: extract revenue from the colonies.

John Dickinson helped draft the Continental Congress’s Declaration and Resolves as a response to the coercive acts. In his hope for reconciliation, Dickinson operated within the long English tradition of petitions and declarations, pairing specific grievances with constitutional arguments against them. This tradition was promotive of liberty. Although John Adams later condemned Dickinson as “timid,” there is nothing in the Declaration and Resolves that strikes one as timid. Dickinson knew the response would be reconciliation or war. He did not know, however, that King George III had already spoken in favor of war. Where he differed from Adams, as Murchison puts it, is that Dickinson “hoped for liberty with reconciliation, according to the ancient English pattern.” It may be true, as Kirk argues, that John Adams was the quintessential conservative thinker of this period. Yet in the Adams versus Dickinson controversy over the wisdom of independence, Adams undoubtedly was the more radical of the two, whereas Dickinson exhibited the politics of prudence.

For his contemporaries as well as for later generations of Americans, it is Dickinson’s opposition to independence that has been the most puzzling. Why would Dickinson oppose a move that seemed to many, then and now, to be the natural end point of all his efforts since 1765? And can we determine whether this resulted from anxious cowardice, as John Adams surely thought it did, or from prudence and temperance, the two virtues statesmen need most?

The missing link, according to Calvert, is that “most analyses fail to take seriously the religious climate in which Dickinson lived and worked as well as his own religious belief.” Specifically, says Calvert, this means the effect of Pennsylvania’s Quaker heritage and spiritual and intellectual milieu on Dickinson.

Quaker political theory, argues Calvert, “functioned within a unique constitutional tradition,” because Quakers were “neither Puritans, pietists, nor deists. Neither were they Whigs or Tories, Lockean liberals or classical republicans.” As she points out, what seem to be the “Lockean” bits of Quaker thinking had been formulated by Quakers decades before Locke’s Two Treatises of Government and Letter Concerning Toleration, both of which were published in 1689. Confusion among scholars has resulted, claims Calvert, “because they have not understood the cultural and intellectual tradition in which he was thinking or the theory it produced.”

In The Conservative Affirmation, Willmoore Kendall addresses this alleged Lockean influence. Kendall rejects the oft-repeated claim that the American founders were “under the spell of John Locke and Lockean ideas,” along with Enlightenment social contract theory. The framers were not Lockeans, which is why so many opposed a Bill of Rights at the Constitutional Convention. Kendall compellingly shows the difference between the Lockean social contract idea, which he argues left man with consent as the only basis for obedience to the law, and an “organized society” of transcendent origin that arises from the very fact of man’s humanity and social nature.

As Kendall puts it:

The distinction between the contract (or the idea of the contract) that creates and the contract that specifies is, for both political practice and practical philosophy, fundamental. The Old Testament Covenant, as also the contract to which Socrates appeals in Plato’s brief dialogue The Crito, belong to an entirely different realm of discourse from the “contracts” of, e.g., Locke and Rousseau.

For Kendall, the classical philosophers were the first social contract thinkers, predating the 17th- and 18th-century thinkers by more than 2,000 years.

Kendall cites what he calls the “conventionalist” position, which is the one proposed by Glaucon in Plato’s Republic. This is the Sophist position, where citizens obey laws because either they are forced to do so by their fellow citizens or their “forefathers had agreed to obey them.” Hence, there is no sure way to ascertain right and wrong, so one follows the conventions of one’s polity.

“Against the conventionalist position,” says Kendall, “the classical philosophers urged such propositions as the following:

- The city-state (society) is natural to man.

- Its origin is to be sought in the nature of man, for whose perfection it is necessary.

- Justice … and the law are not artificial or man-made, but rather are discovered by man through the exercise of reason.

- Man … has a duty to subordinate himself to justice, to the principles of right and wrong, and to the law.

So while different societies might do this in particular ways, “the best regime is that which is best for the nature of man.” In other words, the question of the “best regime” is ultimately an anthropological question.

Since St. Augustine, “the Great Tradition of Western political philosophy” has spoken with “a single and clear voice of the subordinate and merely specifying role of promise and consent in man’s search for, and his attempt to achieve, the true purposes of society.” That purpose, says Kendall, is “justice and right.” The social contract theorists like Locke and Rousseau, then, were regressive, not progressive, in their rejection of the transcendent and anthropological origins of human society. According to Kendall, this rejection marked a return to sophistry and left agreement and not truth as the surest ground for society. While the “best regime” will involve consent to be just, it is important to note that how that consent is understood or employed is dependent on culture, time, and place.

This question of the “best regime” was one Dickinson wrestled with. He knew one had to balance historical context, place, and social development with not simply the “best regime” but the best possible regime given current circumstances—taking neither a historicist nor a utopian approach but one rooted in the Western heritage. This heritage understood that some regimes are better than others, and that those that are better are the ones that spring from human nature and are ordered to the dignity of the human person, who is “born free” but not in the way that Rousseau meant. This freedom, rather, is the freedom to seek justice and do good. What Lord Acton called “the right to do what one ought” comes from God, not an agreement among men. This is where the Quaker influence in Dickinson’s thought is most important.

Quakers believed governments and laws to be the sacred result of God’s design and providential will. Therefore, these “should not be destroyed by man.” Yet man’s broken and finite nature meant that God could reveal his will only gradually to man, making “change a fundamental aspect of Quaker constitutionalism.” For Quakers, the sacred could evolve. That change can preserve the good and purge the bad is nothing Whigs did not believe, but it turns out that the distinction between evolution and revolution is the demarcation line. Where Quakers differed from Whigs is that “while the Whigs could and did sanction the destruction of government through revolution, the Quakers’ Peace Testimony compelled Friends to take another track.” That track, says Calvert, involved speaking truth to power. This strategy was ultimately preservative, in that it sought to preserve the current constitution even amid critique of the current regime.

Quakers believed governments and laws to be the sacred result of God's design and providential will.

This Quaker influence on Dickinson is especially key to understanding his opposition to American independence in 1776. The Quaker preference for nonviolent resistance and aversion to violent protest and revolution, according to Calvert, combined in Dickinson with Quaker constitutionalism. This may be true but we ought to recall that George Washington, decidedly not a Quaker, also shared a similar opinion of the Boston Tea Party as deleterious to the preservation of Americans’ traditional liberties. Likewise, another non-Quaker, Thomas Jefferson, also preferred nonviolent resistance. Indeed, during his presidency Jefferson’s European and British boycotts decimated New England’s economy in the name of avoiding the warfare in Europe. Washington had done something similar (though without a boycott) with his neutrality policy of the early 1790s. In other words, there is a degree to which these Quaker positions are inseparable from other, genuinely American positions among those who recognized the blessing of North America’s geographical distance from Europe and who cultivated a predisposition for temperance, law and order, and the politics of prudence.

On the other hand, whereas Jefferson and most other Americans (like the English Whigs) had come to view the English Civil War as an example of the growth of liberty amid opposition to oppression, Dickinson agreed with Quakers who “admonished against the overt disrespect for the law that the Puritans demonstrated in the revolt against Charles I” (Calvert). To be clear, Dickinson was no pacifist, and he did lead men into combat during the Revolutionary War. But in 1776 he thought independence was premature. In his prudential judgment, though events later proved him wrong, Americans would be more likely to lose their liberties outside the British Empire than inside it. As he put it, independence would lead to “a multitude of Commonwealths, crimes and Calamities—centuries of mutual Jealousies, Hatreds, Wars and Devastations, until at last the exhausted Provinces shall sink into Slavery under the yoke of some fortunate conqueror.”

This concern for order, ever the concern of the conservative mind, explains Dickinson’s influential role as the primary author of the first constitution of the United States, the Articles of Confederation. The Articles were written in 1777 but not approved until 1781. The “Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union” established a small general government. To preserve the “sovereignty, freedom, and independence” of the states within the structure of a loose federal union, there was no national executive, judiciary, or army. Everything was governed by congressional committees. Every state had an equal vote and each also had to approve national taxes for them to go into effect. The traditional interpretation of the Articles is that they created an imbalance between state and national power that led to economic problems, trade and territorial disputes, and, by 1786, outright rebellion in the case of Massachusetts.

When the Articles appeared insufficient to avoid the kind of “Calamities” he had feared, Dickinson supported replacing them with the U.S. Constitution. In 1788, to win ratification, he wrote The Letters of Fabius. Just as Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison penned The Federalist Papers under the pseudonym Publius, Dickinson wrote under the name Fabius, a reference to the Roman general Quintus Fabius Maximus. “Fabian” comes down to us more as an adjective that means an incessant delayer of action. The real Fabius successfully employed a strategy of hit-and-run tactics to degrade Hannibal’s invading army during the Second Punic War. The facts are that Fabius distracted Hannibal long enough to allow the Romans to expel him from the Italian peninsula. In the end, after criticizing his strategy of avoiding the frontal assault, Hannibal praised Fabius as an excellent general. The point is that Dickinson’s choice of pseudonym signaled his prudential strategy of careful plodding combined with strong argument. And in an age of classically educated gentlemen who knew as much if not more about Roman history than even English history, few would have misunderstood the significance of Dickinson’s choice of pseudonym.

Dickinson, writing as Fabius, is concerned about “disorder, jealousy and resentment” among the states. This cauldron of passions, he worries, is “fatal to confederacies of republics,” and as evidence he cites St. Paul’s words, along with the rise and fall of the ancient poleis of Greece and republican Rome. Dickinson argues that the U.S. Constitution will strike the right balance between liberty and order so that the liberty can be secure. Washington, who had mastered Fabian tactics while general and who shared Dickinson’s temperament, actively promoted the republication of the Letters of Fabius.

The Fabius letters are more than just another example of American arguments to ratify the Constitution, for they evince a deep Christian anthropological vision of society. It is a vision steeped in the classical and Christian understanding of the social nature of man, his innate freedom, and the purpose of government. “Our Creator designed men for society,” he writes, “because otherwise they cannot be happy.” Dickinson rejected what Kendall calls the “conventionalist” social contract theory and “state of nature” nonsense and proposed in its place the classical and Christian argument that society is natural to man and has a telos. Gregory Ahern argues that “for Dickinson, political society has a moral as well as a practical end.” The moral end, Dickinson says, is to be not only “great, respectable, free, and happy” as a country “but also VIRTUOUS.” The free and virtuous society is the aim of good government because it best accords with who the human person is, in all his dignity. Dickinson recognized there could be no one-size-fits-all constitution, but he did claim that the U.S. Constitution “is the regime which most conforms with human nature.”

Dickinson’s religiously informed foundation, which recognized the transcendent truth of human nature while prudently applying moral principles, law, and inherited wisdom to current questions, is a good shorthand definition of American conservatism. It was not specifically Quaker to argue, as Dickinson did of the source of natural rights in 1776, that “our liberties do not come from charters; for these are only the declarations of preexisting rights. They do not depend on parchment or seals; but come from the King of Kings and the Lord of all the Earth.” More importantly, concepts like consent and representation did not spring from the secular Enlightenment or find their terminal roots in England, nor were they the distinctive product of Pennsylvania.

The idea of rule by consent, especially where property is concerned (i.e., taxation of one’s justly earned wealth), can be found explicitly in the sixth-century code of Justinian: Quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbari (What touches all must be approved by all). Dickinson refers to this in The Letters of Fabius.

Prudently applying moral principles, law, and inherited wisdom to current questions is a good shorthand definition of American conservatism.

We can, in fact, trace the rise of advice and consent. For instance, Pope Alexander III in the 12th century required advice and consent of clergy in cases involving property. The Third Lateran Council, in 1179, set parameters for the right to vote in the major reform that established the College of Cardinals. A vote of two-thirds became the norm, with Pope Gregory X arguing that two-thirds represented the right amount (i.e., more than a simple majority).

Other forms of consent that deepened over the ensuing centuries included the requirement of mutual consent in marriage. Meanwhile, clergy elected deans of cathedrals, chapters elected their officers, and this was all done by secret ballots. According to Robert R. Reilly, who details this history in America on Trial, the “canonists vastly expanded and applied this rule to ecclesiastical corporations in order to underpin the practice of self-government within religious orders, dioceses, abbeys, and the entire Church, especially as it applied to taxation and legislation.” Thomas Aquinas formulated this as “the directing of anything to the end concerns him to whom the end belongs.”

Innocent III applied the quod omnes tangit to the Fourth Lateran Council, in 1215, by inviting the provosts and deans of churches (themselves elected by chapters), because the matter under consideration involved schools and how to get the financial resources to support them. The Dominican system of elective rule was established by Dominic himself in 1220.

When Dickinson talked about “no taxation without representation,” he was drawing on an idea of consent that already had deep roots in the Western Christian heritage. The American experience existed in continuity with that heritage, stretching back through Pope Alexander III in the 12th century to Justinian in the 500s. And even that, of course, had roots traceable to rules on justice and property in the book of Leviticus and elsewhere in the Hebrew scriptures.

Looking at Dickinson should remind us that he, like most of the other American founders, was not part of a new, fundamentally secular liberalism. We must not conflate the liberal ideas we find among leading American founders with radical, atheistic versions of liberalism we see in the 18th century and up to the present. But to the extent that consent of the governed is considered a liberal principle today, we should conclude that, at least in that regard, liberalism in substance has older, Christian foundations. This foundation is what enabled Dickinson, with both moderation and prudence, to argue that a constitutional republic would best allow Americans to sustain a free, happy, and virtuous society.