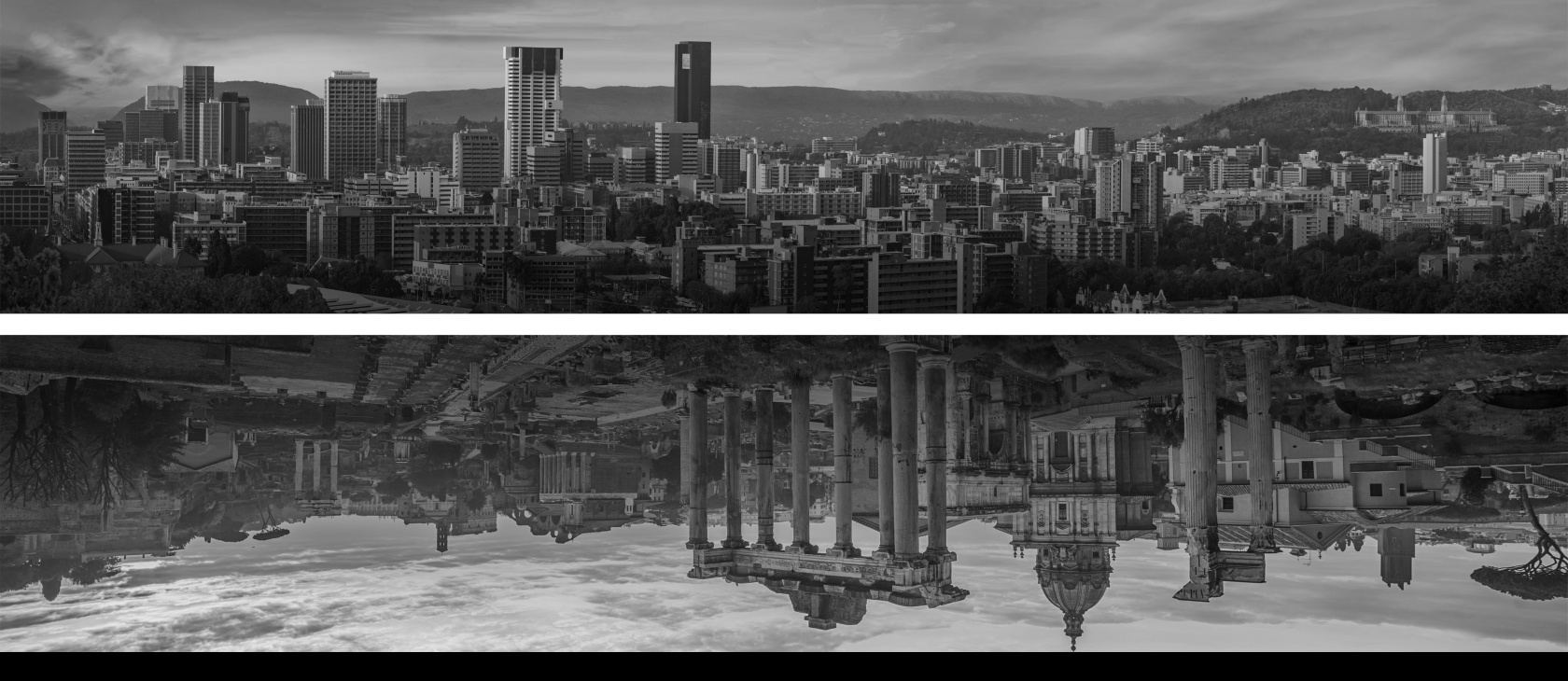

Tertullian famously asked, “What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?” In the spirit of that ancient African theologian, let us ask a similar question: “What has Rome to do with Pretoria?” What does the sacking of Rome in 410 have to do with South Africa in 2025?

The city of man may have failed to bring prosperity to South Africa, but the City of God, in the form of the church, abides in faith, hope, and charity.

Modern South Africa is worlds away from fifth-century Rome. One is African; the other European. One is modern; the other ancient. And beyond geography and time, these places have radical differences when it comes to some pivotal moments in their histories. Rome was taken down from the outside as King Alaric came in with Visigoth forces and dismantled the existing government. South Africa’s apartheid government was revolutionized from within as Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress dismantled racist apartheid policies. It is hard to imagine any connection between the city of Rome in 410 and South Africa in 2025.

And yet, Saint Augustine has something to say to both yesterday’s Rome and today’s Pretoria. The political realism of Augustine’s City of God speaks to the unrealized idealism of the African National Congress (ANC) and its recent fall from absolute majority. And as we shall see, this early church theologian from the northern end of Africa has something to say about the enduring role of the Christian church on the southern end of Africa.

Augustine’s insights are not just for the Rainbow Nation, but for all nations and for all who dwell therein—though the city of man may perish, the city of God persists.

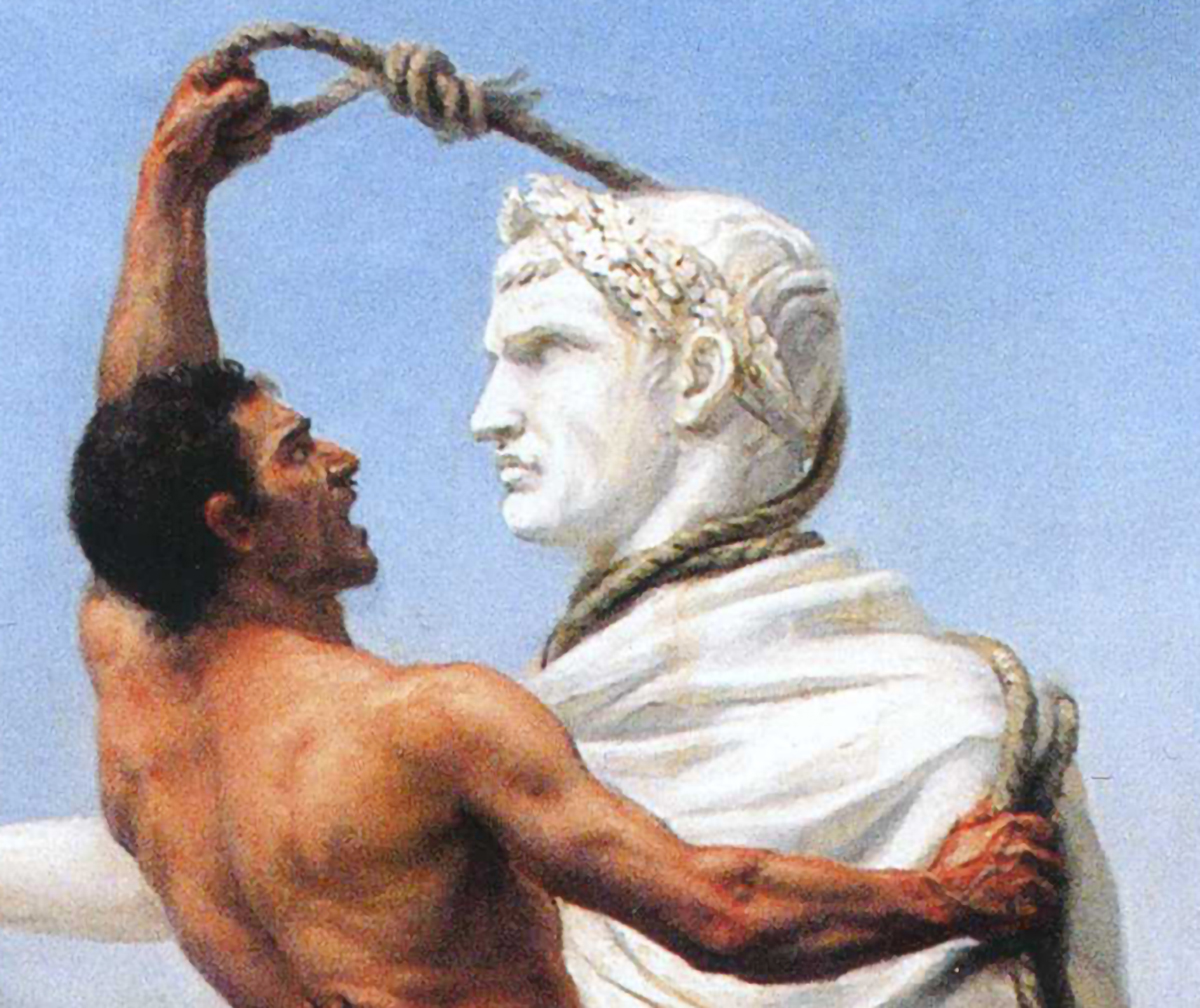

Augustine’s classic tome City of God was prompted by the sack of Rome at the hands of the Visigoths in 410. Though the city was no longer the administrative capital of the western Roman Empire, it was still the “eternal city” and the spiritual center of the empire. Alaric and his troops entered the city on August 24, 410. This was the first time in nearly a millennium that a foreign invader had successfully pillaged the city. The upheaval created a societal and existential crisis for many Romans.

Religion was at the center of the crisis. Did Rome fall because many Romans had abandoned the old pagan gods? Was Constantine’s conversion to Christianity some hundred years earlier to blame for the city’s demise? Or had the Arian Christianity of Alaric—a heretical sect that denied the eternal nature of Jesus—actually saved the lives of many Romans since the invaders had spared them for Christ’s sake?

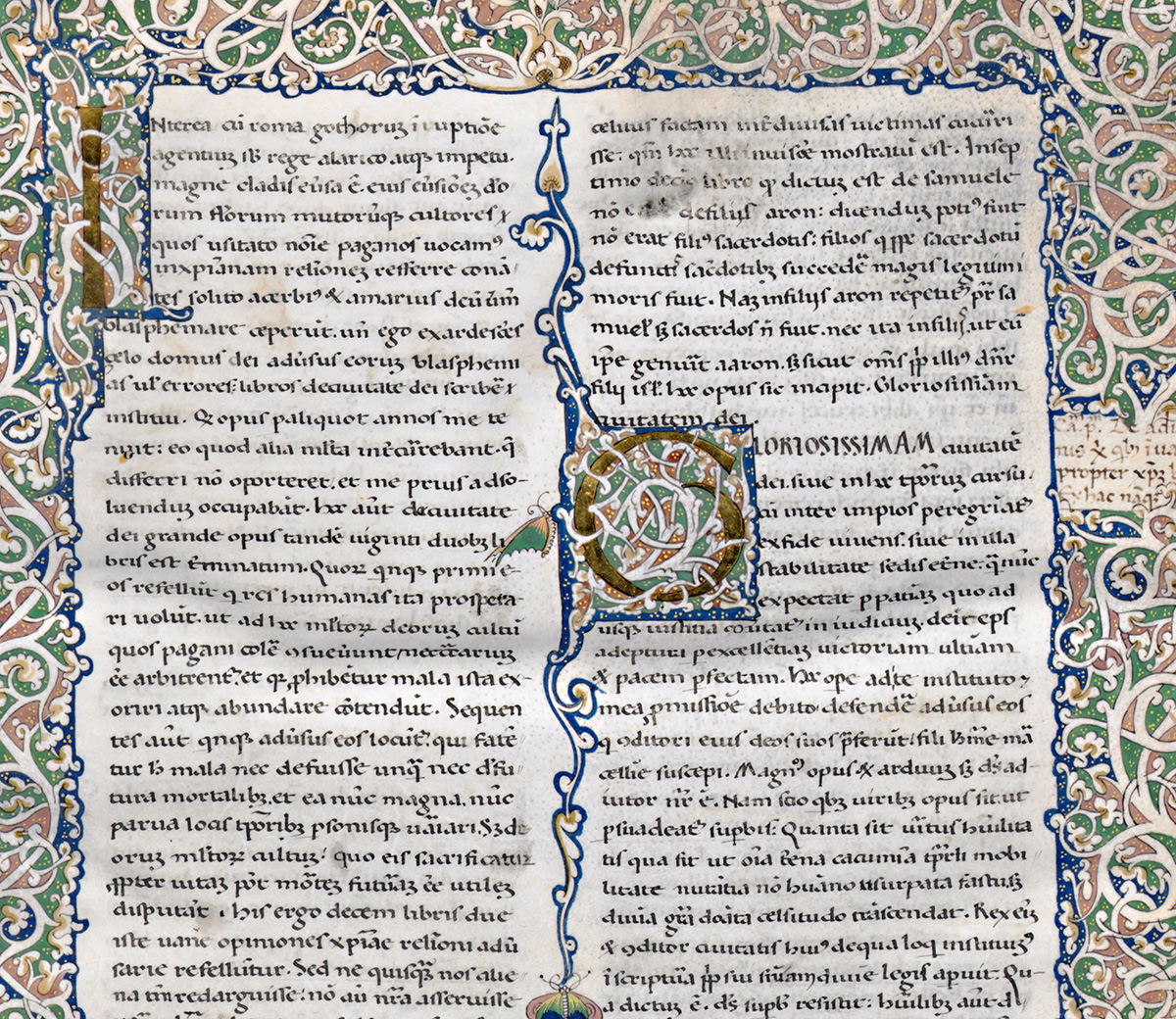

Augustine’s City of God addressed these and many of the other questions that Romans were asking amid the smoke and rubble. In doing so, Augustine made a distinction between the cities of this world (civitas terrena) and the City of God (civitas Dei). Augustine began his project by writing in the preface, “I cannot refrain from speaking about the city of this world, which aims at dominion, which holds nations in enslavement, but is itself dominated by that very lust of domination.”

The lust of domination—libido dominandi—animates the city of man and its leaders. And yet, the will to dominate brings an endless cycle of enslavement that is itself enslaving; the will to dominate dominates political rulers within the city of man. For example, the Year of Five Emperors (193 AD) saw Roman emperors murdered, assassinated, executed, and divided by civil war. According to Augustine and evinced by history, the city of man seeks to take and hold power—which is a violent and fragile game.

Books 2 through 4 of City of God is where Augustine lays out his political philosophy. Augustine was, according to theologian Reinhold Niebuhr in his essay “Augustine’s Political Realism,” the first great political realist. Augustine’s political realism sought to lift the veil of idealism by speaking truthfully about human depravity, man’s voracious “self-love,” and the existence of evil. It also led him to speak some hard words about the Roman Empire and what brought about the fall of the city of Rome. In book 4, chapter 3 of City of God, Augustine writes how it is foolish:

to glory in the greatness and extent of the empire, when you cannot point out the happiness of men who are always rolling, with dark fear and cruel lust, in warlike slaughters and in blood, which, whether shed in civil or foreign war, is still human blood; so that their joy may be compared to glass in its fragile splendor, of which one is horribly afraid lest it should be suddenly broken in pieces.

Human empires possess a china-like fragility according to Augustine. A knife, a coup, or, in the case of Rome, an open gate can topple them. Along with exposing the delicacy of earthly power, Augustine’s political realism reveals how earthly kingdoms are stained with a patina of piracy, as he writes in book 4, chapter 4:

Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms? ... Indeed, that was an apt and true reply which was given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had been seized. For when that king had asked the man what he meant by keeping hostile possession of the sea, he answered with bold pride, “What do you mean by seizing the whole earth; but because I do it with a petty ship, I am called a robber, while you who does it with a great fleet are styled emperor.”

The difference between pirates and emperors, according to Augustine, is simply a matter of scale. Like pirates, emperors take hostile possession of goods and power and seize a kingdom on earth for themselves. Merchants, on the other hand, received a more favorable appraisal from Augustine. According to Murray Rothbard, in his book Economic Thought Before Adam Smith, Augustine deemed merchants and their work in transporting and selling goods as worthy of compensation and capable of godly service to neighbors. It would seem that Augustine put free enterprise in a different category than he did pirates and emperors.

The difference between pirates and emperors, according to Augustine, is simply a matter of scale.

In stark difference to the city of man, Augustine presents to us the City of God. Though not a physical place, the City of God is a spiritual community oriented toward the love of God:

Two cities have been formed by two loves: the earthly by the love of self, even to the contempt of God; the heavenly by the love of God, even to the contempt of self. The former, in a word, glories in itself, the latter in the Lord. For the one seeks glory from men; but the greatest glory of the other is God, the witness of conscience. The one lifts up its head in its own glory; the other says to its God, “Thou art my glory, and the lifter up of mine head.” (book 14, chapter 28)

These two cities intersect and intermingle—yet can be distinguished from one another. While all are born into the city of man, God’s grace gathers a redeemed community into the City of God. Augustine’s political realism, however, never lapses into a lofty idealism wherein the goal becomes achieving the City of God on earth. Human depravity and a fallen world prohibit the construction of heaven on earth. Rather, those who dwell in both the City of God and the city of man live in both realities, loving and glorying in God while serving one another in love.

Augustine brought realism to Rome and comfort to a crumbling city with his permanently relevant message: Though the city of man may perish, the city of God persists. Though we see the city of man rising and falling around us, look also for the enduring city of God hidden within it.

Though not exactly the fall of Rome, after 30 years of political hegemony the ANC has fallen from exclusive power and has been forced to enter into a coalition government. On June 14, 2024, the ANC lost its parliamentary majority and formed a coalition with the Democratic Alliance, the Inkatha Freedom Party, and the Patriotic Alliance. Eventually six other parties joined as well, forming a grand coalition.

While Cyril Ramaphosa has retained his position as president of South Africa, support for the ANC has significantly declined. In 1994, Nelson Mandela received 62% of the general election vote as the ANC won a sweeping victory to end the apartheid government. Now, 30 years later, Cyril Ramaphosa and the ANC received just 40% of the vote in the 2024 general election.

Ramaphosa’s time as president of South Africa began with lofty idealism. Chris Brown, in his introductory chapter of New Leaders, New Dawns? South Africa and Zimbabwe under Cyril Ramaphosa and Emmerson Mnangagwa, describes the idealism that marked the early days of Ramaphosa’s presidency:

[Ramaphosa] has a long history in the liberation movement, including serving as the ANC’s chief negotiator in the talks leading to the end of apartheid, before leaving politics and launching a successful business career that saw him become one of South Africa’s richest men. Having returned to politics, his ascension to the presidency was greeted with near euphoria by many in South Africa, who looked to him to end corruption, reverse state capture, and put the economy back on a solid footing.

These hopes, however, remain unrealized. Though Ramaphosa promised a “new dawn” in his inaugural address to Parliament in 2018, this day has eluded South Africa over the past seven years. According to the Gini Index, a statistical measure of wealth distribution and inequality, South Africa has an index of 63—the highest income inequality in the entire world. Problems with critical infrastructure make water shortages and loadshedding (rolling blackouts) a part of daily life for South Africans.

Christians in South Africa offer both a sober view of humanity and an enduring happiness in hope.

South Africa, however, has a unique opportunity in 2025 as it assumes the presidency of the Group of 20, often referred to as the G20. The themes for South Africa’s presidency will focus on challenges related to poverty, unemployment, and inequality. Nevertheless, South Africa has been here before on the world’s stage: hosting the 1995 Rugby World Cup, hosting the 2010 FIFA World Cup, and becoming a member of the geopolitical bloc BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa). While these pivotal opportunities have been a source of pride for post-apartheid South Africa, they have not really brought steady flourishing to the country.

As political realism sets in for South Africa, the search for a free and virtuous society is revealing how the Rainbow Nation needs the City of God. Amid the rubble of political idealism, the church gives voice to the brute realities of humanity and politics while also revealing the City of God and the hope therein. The South African church of today is revealing the continued relevancy of Augustine’s message from long, long ago.

As the South African government flounders, the church flourishes. As a corrective to wishful idealism, Christians in South Africa offer both a sober view of humanity and an enduring happiness in hope. Hidden within a struggling nation, the Christian church is a visible outpost of the City of God endeavoring toward a free and virtuous South Africa.

The City of God in South Africa takes many different shapes. For example, Dr. Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela won the Templeton Prize in 2024 for her work in forgiveness, reconciliation, and communal dialogue. Dr. Gobodo-Madikizela served on South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the 1990s and became convinced that human beings are a “constellation of contradictions” capable of both evil and good. This understanding of humanity resembles an Augustinian anthropology: Though humans are made in the image of God, evil arises as humans reject God’s design and act according to their own sinful desires within the cities of man.

Gobodo-Madikizela’s work centers on the reconciling power of forgiveness—something that the church in South Africa is uniquely able to instantiate. Unlike the city of man and its misaligned loves and insatiable will to dominate, the Christian church is a community formed by the good news of the gospel and realigned to both God and neighbor through rightly aimed loves.

The Christian church in South Africa is where healing and hope, flourishing and virtue, are emerging. According to Gobodo-Madikizela, in an interview with Duke Divinity School’s Faith and Leadership: “Churches have a very important role to play. The church already has a group of people who are ready to receive the good news. And the good news is not only biblical good news; it is also doing the work to make sure that people live in a spirit of good news.”

The Confessional Lutheran Synod of South Africa (CLSSA) is another example of the City of God dwelling amid the South African cities of man. David Tswaedi, bishop of the CLSSA church body, describes how the church in South Africa stands against the vices of a sinful society:

The level of corruption by civil servants and politicians [is] symptomatic of the loss of guilt and a sense of shame and sin. The prophetic voice of the church to call sin what it is—rebellion against God—cannot be compromised. The Biblical church continues to preach this message because it has been the real antidote against pseudo self-righteousness. … Where God’s Word is taught and preached in its purity, the fruits of the healing message are evident.

This prophetic voice of the church in South Africa is backed by action. Not only does the church speak plainly about human depravity, but it is also working to bring tangible hope to otherwise hopeless communities. The CLSSA, in partnership with a U.S.-based nonprofit organization called Christian Outreach for Africa (COFA), operates Christian schools for hundreds of children. As the church provides quality Christian education in South Africa, the civitas Dei flourishes amid the rubble of apartheid and the unrealized dreams of political idealism.

“It is a known fact that South Africa is one of the most economically unequal countries in the world, with a few wealthy persons, mostly White, and the masses that are poor, which are mostly Black,” said Bishop Tswaedi.

Though the South African government has been working to address this issue for several decades, the church and nonprofit enterprises are actually bringing about steady flourishing. According to Bishop Tswaedi, “The CLSSA saw an opportunity to provide good and affordable education for the disadvantaged Black children. … In partnership with COFA, a pre-school was started and this gave birth to a high school.”

COFA is one of the key partners for this work in South Africa. This Christian nonprofit was formed in 2016 by Gary Grom, a former senior vice-president with Sara Lee Corporation, and Jerry Kehe, former president and CEO of KeHE Distributing. Recognizing the tremendous need in South Africa, COFA engages in economically viable capital projects that can be sustained by the local community. This non-governmental organization is filling a void while partnering with churches and local private enterprise to bring a new dawn to South Africa.

The prophetic voice of the church in South Africa is backed by action.

Grom describes how partnering with local South African entrepreneurs is offering hope for the community:

I have little hope in the government helping to solve South Africa’s problems. The government is not the answer. I do, however, have some hope that the corporations in South Africa can help us solve some of these problems. Private enterprise and companies have employees living in the townships, and we are there providing a service to their employees.

St. Peter Christian College in Middelburg, South Africa, is one of those community services. St. Peter is an independent, nonprofit primary and secondary school for children. Yet another outpost of the civitas Dei, the school is attracting the attention of the entire community as a place where a more hopeful and virtuous society is forming. Crumbling government-run schools are prompting parents to look to the church for help.

“With ill-discipline increasing in schools, from teachers to students, more and more parents enroll their children in private Christian schools,” said Bishop Tswaedi.

St. Peter Christian College is a collaborative endeavor between the church (CCLSA) and nonprofits (COFA), South African–based leaders and North American associates. While schools like St. Peter are local outposts of the City of God in otherwise struggling places, they are also beacons pointing to a much larger community of hope: “Knowing that Christians from another part of the world care about them and their children helps bring hope in the midst of their hardships. Through COFA, we have earned credibility in the community and they know that we are there for the long haul,” said Grom.

From Africa to Rome and beyond, Augustine’s influence has profoundly influenced generations of people around the world. City of God is a classic and mainstay within the Western canon.

And yet this once cherished work has become buried under the rubble of time and indifference. Many contemporary Americans would struggle to explain how Augustine’s realist vision can speak a word of caution against political idealism and an ever-expanding government.

As Rome fell, Augustine—born in what is now modern-day Algeria—had something valuable to say to the rest of the world. Today, the church at the southern tip of Africa has something very valuable to say to the rest of the world.

What have Cape Town, Bloemfontein, and Pretoria to do with Washington, London, and Berlin? The message of the church in South Africa echoes Augustine’s message long ago: If and when the cities of man perish, the City of God persists. The Christian church is uniquely situated to offer not only a sober view of humanity but also enduring happiness in hope.

Near the end of City of God (book 20, chapter 30), Augustine quotes the Prophet Isaiah. Augustine argues for the permanent relevancy of Christ Jesus and the community of people gathered around him: “He will not grow faint or be discouraged till he has established justice in the earth; and the coastlands wait for his law” (Isa. 42:4).

Eternal words are always contemporary. These words were relevant for the Israelites driven from the rubble of Jerusalem to the coastlands of Babylon. These words were relevant for the Romans driven from the rubble of central Italy to the coastlands of Ostia and elsewhere. And these words have relevancy for all nations and everyone dwelling within the cities of man and the City of God. Hoping in earthly powers and their endless lust for domination is bound to result in death, disappointment, or both. Hoping in the heavenly city hidden in the midst of this world is where we find enduring love and virtue, freedom and flourishing.