Actors in history are not pure spirits for whom the whole of human life is “intelligible and spiritually transparent,” English historian Christopher Dawson (1889–1970) wrote in his 1939 book Beyond Politics. Rather, they are like sailors on a ship, struggling between stormy skies above and dark waves below, amid obscurity and incalculability. They inhabit a “middle earth of life and history,” which is a “great intermediate region” subject to forces “both higher and lower than reason.” Within this tempestuous realm, Dawson located human culture as the common way of life of a people.

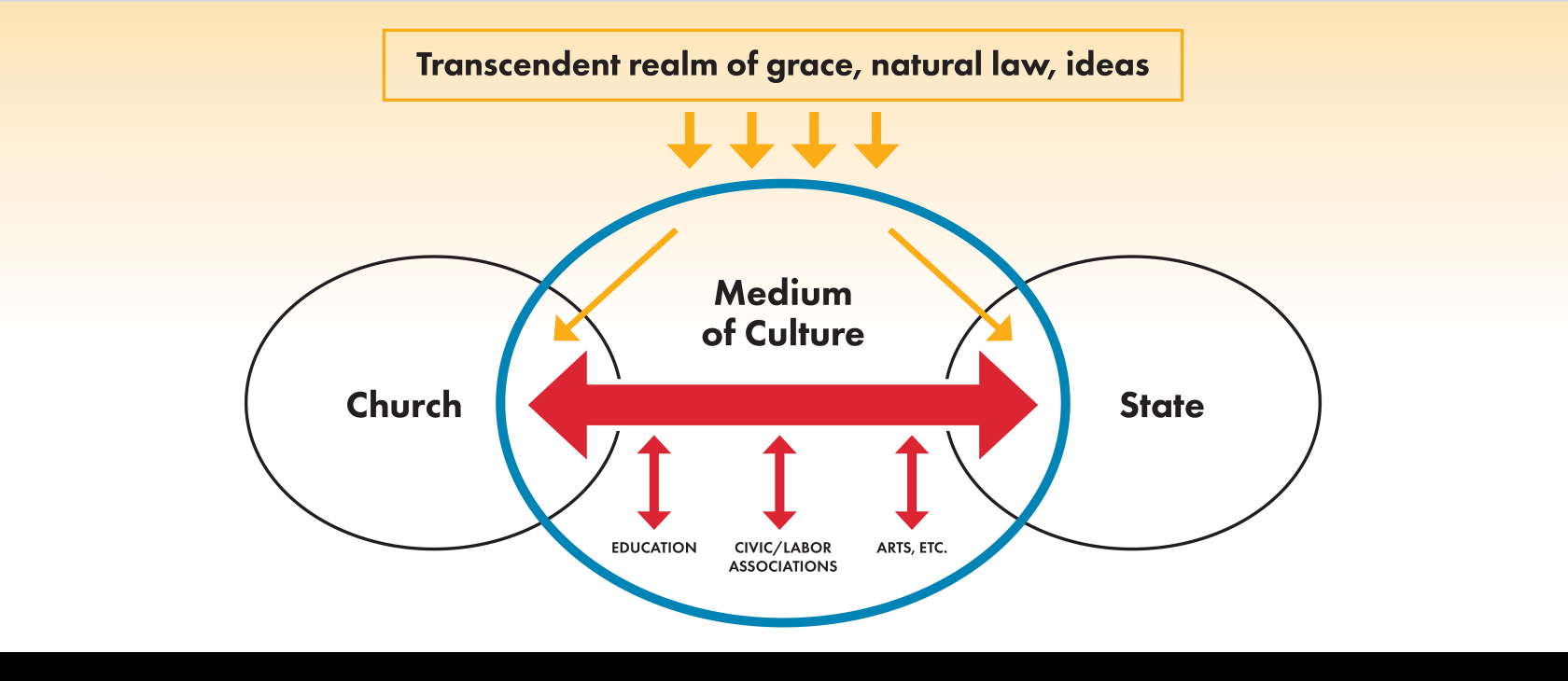

Throughout his histories, Dawson portrayed culture as a medium, a substance in the middle through which forces act, a form of communication, and an environment providing nutrients for life. In Dawson’s political writings, culture mediated between church and state, allowed intellectuals and voluntary associations to shape social order, and refracted the light of transcendent truths into particular places and times.

Dawson’s approach to culture as a medium helped him avoid any stark separation of church and state, as criticized by some (e.g., Gilbrian Stoy) in the work of Jacques Maritain as an unstable formulation putting the temporal order into teleological crisis. Dawson also steered away from the kind of Christian nationalism or Catholic integralism promoted recently in the United States. His political thought prefigured that of public intellectuals today like George Weigel and Paul D. Miller who take culture seriously and seem to occupy a position in between the conservative and classical liberal traditions. Economist Barbara Ward, Dawson’s friend, remembered how he defended the “constitutional center with its natural law basis” from the radical political extremes on either side.

Economist Barbara Ward, Dawson's friend, remembered how he defended the 'constitutional center with its natural law basis' from the radical political extremes on either side.

Dawson entered the Catholic Church in 1914, was elected to the British Academy in 1943, and ended his career as professor of Catholic Studies at Harvard University (1958–62). His books attracted wide attention in the mid-20th century, and the republished Works of Christopher Dawson series has sold tens of thousands of copies since 2001. He is remembered as one of the greatest Catholic minds of the 20th century.

Dawson wrote about politics mostly during the 1930s. Historian James Chappel recently argued that Catholics “became modern” during this transformative decade because totalitarianism forced them to drop their anti-modernism and rethink their relationship to modernity. Catholics in Germany, France, and Austria began to accept political modernity conceptually (more than just pragmatically) in its distinction between the secular public sphere and the religious private sphere. They gave up the ideal of a “Catholic state” to ally with any one of good will. Catholics shifted from speaking of the “rights of the Church” to “human rights.”

In Britain, Christopher Dawson largely followed this trajectory. At first, he shared the general postliberal assessment of his time that the Great War and the Great Depression had undermined constitutional democracy. He read papal social encyclicals against the backdrop of this cultural diagnosis. During the mid-1930s, Dawson admired the coupling of “Christian corporatism” with state power in places like Italy, Austria, and Spain even while warning against totalitarian tendencies operating roughly equally across the West.

By the late-1930s, however, events compelled Dawson to shift his postliberal diagnosis. The liberal tradition was not dead, nor was totalitarianism equally operative across the West. He rethought his application of Catholic social teaching to contemporary regimes as he returned to an earlier appreciation of the British political tradition featured in his 1931 talks for the BBC on the deep European and Christian roots of constitutional democracy. His new confidence in freely organized culture rather than central control manifested in his leadership of the Sword of the Spirit movement to unite British Catholics behind the war effort in 1940.

“If it is not the Church’s business to organize culture, neither is it that of the State,” Dawson wrote in Beyond Politics. “It [culture] is an intermediate region which belongs to neither the one nor the other, but which has its own laws of life and its own right to self-determination and self-direction.” The sphere of culture overlaps with church and state, but it is not coterminous with either, preserving space for personality and for spiritual freedom.

How could the sphere of culture be freely directed toward spiritual ends? For Dawson, this was “the greatest need of our civilization,” for the realm of culture had become a “no-man’s land” of anarchic individualism. An easy temptation was to subordinate the cultural sphere to ecclesiastical or political governance. Christians, however, believed the Kingdom of God existed as a leaven under the surface of the present order to transform it by the power of the Holy Spirit. Culture was a medium of grace and not to be worshipped as an end it itself.

'It is not the Church's business to organize culture. Neither is it that of the State.'

Dawson believed that the spiritual ordering of culture could be achieved only by a power of the cultural order: “that is to say by the power of ideas and the organization of thought.” Intellectuals should serve not the interests of political power but those of the wider community of thought transcending any single political society. He stated boldly in his last major political work, The Judgment of the Nations (1942): “The liberties which we demand and which humanity demands, are … the elementary rights which are to the human spirit what air and light are to the body;—freedom to worship God, freedom of speech, freedom from want and freedom from fear. Without these man cannot be fully man, and the order that denies them is an inhuman Order.”

In addition, Dawson believed diffuse voluntary organizations with common ends and a corporatist spirit could collaborate to effect cultural discipline across British society. The cinema, the theater, the press, the schools—each should strive to be an “independent spiritual organ of the community,” he wrote in Beyond Politics. An independent sphere of culture did not thereby relegate the church to public irrelevance. Religion inevitably but indirectly influenced the state through the medium of culture, even as, implicitly, influence could move in both directions.

Finally, Dawson put culture squarely at the center of his political thought rather than ideas or ideologies. It was useless to talk about ideas such as liberalism in the abstract apart from the concrete cultural and historical background of the different forms of liberalism.

This meant that, with Edmund Burke, Dawson recognized the frequent contradictions between human aims and historical results when trying to realize social ideals in practice. Seeking perfect justice might undermine justice. As Burke wrote in Reflections on the Revolution in France, “Metaphysic rights entering into common life, like rays of light which pierce into a dense medium, are by the laws of nature refracted from their straight line.” Rights exist in a sort of middle, Burke argued, in the “dense medium” of human culture and in compromises between goods or even between good and evil. Principle does not translate immediately into policy.

In conclusion, Dawson defended powerful ideas of the classical liberal tradition like separation of church and state, the independence of culture, and individual rights. At the same time, he robustly advocated culture as a medium through which spiritual forces might influence and even reconsecrate social and political order. In short, he articulated conservative realism against ideological utopianism in support of national well-being.