For this special “poverty” issue of Religion & Liberty, I was asked to revisit two of my books, The Tragedy of American Compassion (written in 1990) and Compassionate Conservatism (1999). My brief was to (1) address what I had originally hoped to accomplish with those works; (2) discuss whether a “compassionate conservatism” ever resonated with the American public; (3) summarize what has transpired in terms of poverty intervention and amelioration on the federal, state, and local levels; (4) show where we are now; (5) answer the question, “Is the road ahead now different in some ways from what you outlined in your two books?”

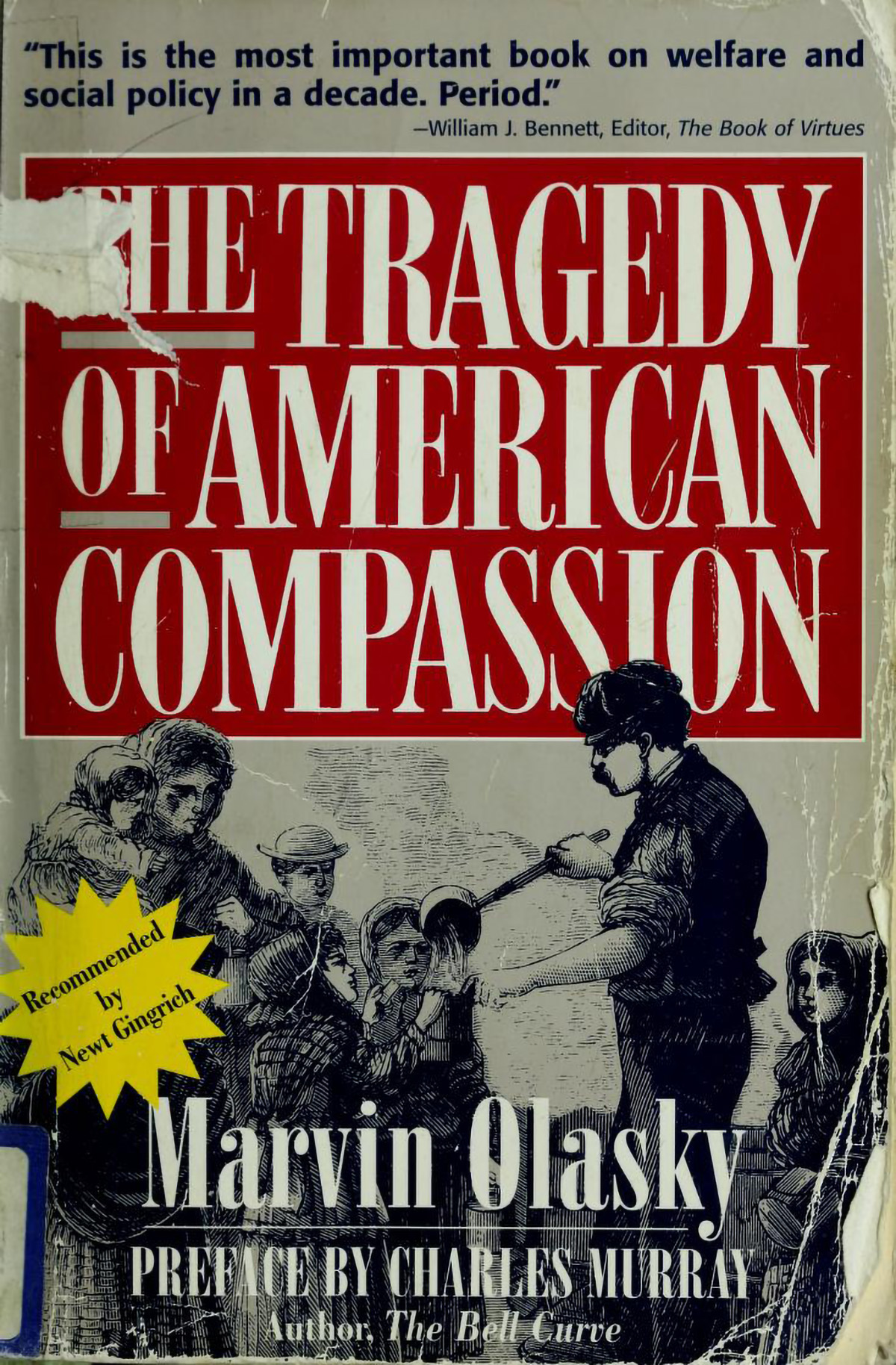

Thirty-plus years ago a book landed like a bombshell in the nation’s capital: The Tragedy of American Compassion. It ignited a movement that put helping the poor front and center of all citizens’ lives. How compassionate was it? How conservative was it? What happened to it?

I’ve been given 5,000 words for what could easily take a million. Nevertheless, here we go.

1. What had I hoped to accomplish?

Initially, not much.

I had just gained tenure at the University of Texas at Austin when an official at the Heritage Foundation in 1989 said he would welcome an application from me to spend a year in Washington researching a book. That seemed like fun for me and my family. I had to write a one-page proposal explaining my intentions. Hmm: What did I want to write about?

I knew how frequently the Bible treated the subject of poverty. I knew Americans in the 19th century read the Bible regularly. So, wouldn’t some of them have tried to apply the Bible to poverty issues? Standard histories of poverty-fighting suggested that Americans became involved in fighting poverty only once the federal government in the 20th century had begun to take action. My suspicion was that couldn’t be right. There must be more to the story. My proposal to Heritage: I’ll seek the rest of the story.

In 1989–90, I researched and wrote a draft, thinking in terms of an academic publisher. Then a major publisher became interested in it, and I spent the summer of 1990 furiously reorganizing and rewriting to make it more readable. That publisher eventually turned it down, saying it was “too religious.” In fact, it really wasn’t very religious at all, except that I reported positively about what many Christian charities (and some Jewish ones) did.

The book, titled The Tragedy of American Compassion, came out two years later from what was then a small conservative publisher, Regnery. (It’s now a large and very conservative publisher.) Regnery didn’t do much marketing. By the end of 1992, it seemed like the book was stranded at first base. But one huge event moved it to second base. The United States after 45 years had won the Cold War. The Soviet Union had disintegrated. The U.S. during the 1990s had no major foreign enemies, or so we thought, so full attention could turn to domestic problems.

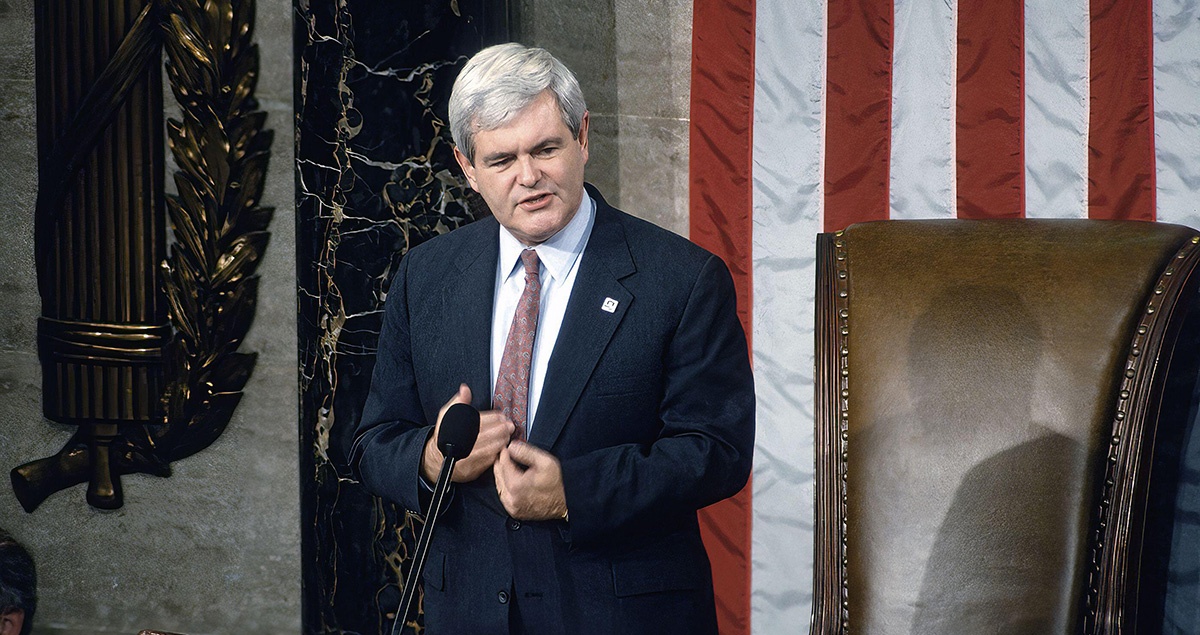

Another event moved the book to third base: in November 1994, Republicans gained a majority in the House of Representatives for the first time in 40 years. Newt Gingrich became speaker of the House. Former secretary of education William Bennett had read The Tragedy of American Compassion and passed it on to Gingrich just as Newt was preparing his first speech to Congress upon becoming speaker. Networks planned to televise it on January 4, 1995.

That day my wife and I turned on the TV in our Austin living room, largely as background noise while I wrote syllabi for the spring term University of Texas courses I planned to teach. Suddenly, Gingrich was saying, “I commend to all of you Marvin Olasky’s The Tragedy of American Compassion. Olasky goes back for 300 years and looks at what has worked in America: how we have helped people rise beyond poverty, how we have reached out to save people.”

That announcement was a total surprise for me. (It turns out that a Gingrich staffer was supposed to give me a heads-up but forgot.) For a professor, this was a lightning strike. As soon as Tom Brokaw asked on the NBC Nightly News, “Who is this mystery man?” and an Atlanta Constitution columnist asked, “Is it Olasky or Mellaski or Alaska or Molasses?” the phone started ringing.

Why, according to Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol, did my central message “hit the conservative movement like a thunderbolt”? My message was simple: Conservatives had lost out to the left on poverty issues because they kept saying welfare was too expensive. But it’s not for a society as rich as ours. It’s stingy, however, when we refuse to offer personal help that recognizes how we are all made in God’s image and that we should not treat others as I treat my dog: Put some food in his bowl, walk him twice a day, don’t expect much from him except entertainment. We can do better than mere welfare handouts, assuming some of us are willing to truly love our neighbors as ourselves.

Gingrich’s favorite foundation, Progress and Freedom, offered to pick up my University of Texas salary so I’d be free from teaching and able to make multiple trips to Washington. From January 1995 through August 1996, I became a Platinum Medallion member on Delta by taking more than 100 flights per year, some from Austin to Washington, others around the country. In Washington I served as a salesman, sometimes trying to convince Republican budget hawks that the goal of welfare reform shouldn’t be primarily about saving money, sometimes trying to convince Democrats not to measure programs by how much money Congress allocates.

2. Did compassionate conservatism resonate with the American people?

That’s hard to say scientifically. In June 2023 I reviewed public opinion polls from the late 1990s and early 2000s and found none that asked clearly about compassionate conservatism as a political philosophy. The term did not become ubiquitous until George W. Bush used it as the central expression of his 1999–2000 campaign to become president. Polling about it thereafter seemed tied to his waxing and waning political fortunes. For example, just before Bush became president in 2001, a Gallup Poll of 1,055 adults showed that “58 percent of Americans believe Bush will govern in a way that is ‘truly compassionate,’ while 39 percent do not”—but what that meant was undefined.

As I met with Washington journalists early in 1995, some seemed receptive to deeper structural changes that could make compassionate conservatism more than a pretty phrase. The Washington Post’s William Raspberry understood that “private charity—whether foster care, self-help centers, or gospel-oriented soup kitchens—manages at least some of the time to turn lives around.” Others—David Broder, Charles Krauthammer, Mort Kondracke—seemed sympathetic to my goals but skeptical about whether anything could beat a Washington-centric approach to welfare. New York Times columnist Peter Steinfels said it the clearest: “Olasky and his allies see … a vast outpouring, from millions of Americans, of personal commitment. … It is an inspiring vision, but is it realistic?”

As I met with Washington journalists early in 1995, some seemed receptive to deeper structural changes that could make compassionate conservatism more than a pretty phrase.

Trying to answer that question, I flew around the country. Since the Count was my favorite Sesame Street character, I once counted 153 cities or towns where I visited organizations created to help the poor. Imitating Hank Snow’s or Johnny Cash’s “I’ve Been Everywhere,” I could sing: San Antonio, San Diego, San Francisco, St. Louis; Nashville, Jacksonville, Louisville, Asheville; Gainesville, Colleyville, Cedarville, Charlottesville: I’ve seen compassion everywhere, man. Virginia Beach, Long Beach, Glendale, Scottsdale; New York City, Kansas City, Grove City, Salt Lake City; Tampa, Columbia, Augusta, Atlanta; Buffalo, Chicago, Plano, Orlando; Jackson, Madison, Tucson, Houston; Washington, Charleston, Boston, Newton: Good Samaritans everywhere.

Compassionate conservatism registered with groups of people in all those cities. I also did some speechifying during those travels, and typically concluded my remarks with this audience-participation question: If you had $500 to give to any poverty-fighting organization, please raise your hand if you would send it to the federal Department of Health and Human Services or some other Washington agency? Typically, no hands went up. How about your state government? City hall? Maybe one or two. How many of you know of a community-based, nongovernmental group in your own area that would do a better job with that $500? A forest of arms.

3. What happened?

Senators John Ashcroft and Dan Coats and Representatives J.C. Watts and Jim Talent introduced legislation to encourage the volunteering of time and money. Ashcroft’s bill, for example, specified that a person who volunteered at least 50 hours a year to an institution directly serving the needy could receive a $500 tax credit—not just a deduction—for a contribution to that institution. I did not expect any legislation to fix the basic problem, but with all our current tendencies to maximize self and abandon others, I saw the value of a charity jumpstart.

Gingrich and other GOP leaders, however, did not back such proposals. Instead, they imposed work requirements and time limits on recipients of AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) and changed the name to TANF (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families). Those changes, with exceptions for mothers of small children and for those physically or mentally unable to work, were positive. AFDC, though, was only one among dozens of federal welfare programs. The others were left untouched.

When George W. Bush became president, he tried to inoculate his new faith-based office against charges that it promoted evangelical doctrines or partisan payoffs. That inoculation included the appointment of John DiIulio, a very eminent Catholic Democratic social scientist from Philadelphia. At that point I observed four main positions about funding groups that claimed to be helping the poor: two on the centralist side and two on the decentralist side.

Some of the centralists followed the traditional liberal approach of funding those organizations with the best lobbying and administration contacts. A second group, led by DiIulio, thought all funding could be done on a scientific basis. As he told the National Association of Evangelicals in March 2001: “We’re taking a deliberative approach and focusing first on conducting our audits, studying competing ideas, weighing competing perspectives, and looking forward to … improving government-by-proxy programs through performance-based grant-making.”

Reihan Salam summarized well in the Washington Post what had happened: ‘The essential problem was that compassionate conservatism was an unstable amalgam of two very different ideas, one good and one very bad.’

On the decentralist side were two other groups: some followed the traditional Social Darwinist view of refusing to spend any money at all, while others agreed with my sense that there should be funding but that it should be decentralized, with taxpayers rather than number-crunching experts making the call as to how and where. I was initially naive enough to think that my approach and DiIulio’s could coexist. But following Bush’s eight years in the White House, Reihan Salam summarized well in the Washington Post what had happened: “The essential problem was that compassionate conservatism was an unstable amalgam of two very different ideas, one good and one very bad. The good idea, encouraging self-help and grass-roots entrepreneurship, was largely abandoned in favor of the bad idea, namely the embrace of central planning.”

Salam reviewed the initial thrill of the movement, which was followed by a big chill: “Compassionate conservatism won George W. Bush the White House in 2000, a year Democrats should have taken in a landslide. But over the next eight years … the GOP came to resemble a gaggle of earmark-chasing charlatans who veered from phony compassion to get-tough border-fence theatrics with dizzying speed.”

Prison Fellowship head Chuck Colson, with Washington experience dating back to the Nixon administration, saw more quickly than I did the warning signs of Bush’s “faith-based initiative” heading in the wrong direction. Colson sent me a long letter that described a “public meeting” to kick off a Philadelphia project involving groups devoted to fighting crime, drugs, and other negative aspects of gang life.

Colson said that, at the Philadelphia meeting, he spoke about “evangelizing the streets of Philadelphia, bringing people to Christ.” Right away project leaders objected to his emphasis on evangelism. They kicked Prison Fellowship off the leadership team. In his letter, Colson connected that experience with a conversation he had “with a very eminent social scientist.” Colson told the academic about a young man who became a Christian and now was “on the streets preaching and reading the Bible to members of gangs.” Colson pointed to this “transformed life” as an example of success. Not so, the academic said, unless social scientists “peer-review” the result.

Colson and I believed evangelism to be important, but we also saw the problem with any standard academic measuring device. Maybe a social scientist, if he asked the right questions, could track a program’s results a year after it ended, although participants scatter and are often hard to find. Just maybe it would be possible to contact a representative sample after three years, although that’s rare. But the deeper question is what happens after 10 or 20 years, and only the rarest of studies lasts that long.

The New Testament parable of the sower describes seed tossed onto a path or amid thorns that proves unfruitful, as well as seed that falls on good soil and produces a great crop. But there’s also seed thrown on rocky ground without much soil that immediately springs up—yet, when the sun rises, such seed is scorched. Without roots, it withers away. Colson from experience knew that measuring what immediately grows often yields a false sense of satisfaction.

In March, DiIulio and I took our differences to the National Association of Evangelicals conference in Dallas. DiIulio said a program that urges “each beneficiary to accept Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior” could not receive a government grant. Any program that said, “Your problem is X. To cure X, believe Y” would not qualify. DiIulio said his goal was to fund the most effective programs, but I asked: “What if to cure X, believe J is the most effective way to help people beat their addictions?” “Performance-based” grant-making that bans speaking about Jesus might not be performance-based after all.

4. Where are we now?

Republicans boasted about changing AFDC to TANF. In August 1996 they declared victory: “Mission accomplished.” That was true, partly and temporarily. In 2000 the Cleveland Plain Dealer reported changes in Ohio: “Many of the 111,000 families leaving welfare are doing so because family members have found work. ... A survey conducted for the state found that a year after leaving welfare, 66 percent of the people were employed, averaging 38 hours a week.”

But the mission, although announced in grand terms, was too small. Congress left dozens of welfare programs intact. Since 1996 the number of people on SSDI (Social Security Disability Insurance) has almost doubled. SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) is up 60%. SSI (Supplemental Security Income) is up 30%. Many welfare recipients just slid over to another program.

That’s exactly what happened in St. Paul, Minnesota, but it wasn’t the poor people who were the gamers. Some Ramsey County case managers did not like the idea of work requirements and a five-year time limit, so they helped TANF recipients fill out SSI applications. They accompanied potential SSI recipients to appointments. They “advocated for families” to receive cash payments. The county gave case managers the discretion to do “whatever it would take” to get money to individuals who did not qualify.

Ramsey County officials were proud of their work. As a 2006 document from the research firm Mathematica shows, officials “felt they were gathering important information about families nearing the time limit that would interest a broader audience. They therefore contacted Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. (MPR) to work with them to document their findings.” Back in 1996, Congress thought five years would be enough for most welfare recipients to turn around their lives, but the 2006 document, “When Five Years Is Not Enough,” displays a different perspective.

So what? Welfare is a good thing for the poor, right? Sometimes yes, but it often doesn’t help people fare well. So many of these programs fail in three ways: by not emphasizing work, not emphasizing marriage, and not emphasizing what people can do—as opposed to what people cannot do. Programs that make such mistakes are recipes not for well-fare but for despair-fare (if we practice truth in labeling).

Let’s run through those three errors. First, whatever decreases attachment to work increases poverty. Bible readers know that work is good: Genesis 2:15 says God put man “in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it.” Since the Fall recorded in Genesis 3, work is harder, but it’s still our vocation as human beings. We are hardwired for work, and people with a “loose wire” fare poorly. Every president for the past hundred years has said that those who are physically and mentally able to work should do so.

For example, Franklin Roosevelt in 1935 argued, “We must preserve not only the bodies of the unemployed from destitution but also their self-respect, their self-reliance and courage and determination.” He added:

In this business of relief we are dealing with properly self-respecting Americans to whom a mere dole outrages every instinct of individual independence. Most Americans want to give something for what they get. That something, in this case honest work, is the saving barrier between them and moral disintegration. We propose to build that barrier high.

Work requirements still resonate with the American people. In April 2023, 80% of Wisconsin voters said yes to an advisory referendum question: “Shall able-bodied, childless adults be required to look for work in order to receive taxpayer-funded benefits?” Yes, the referendum was nonbinding, but 80%! When was the last time we saw 80% of the populace agreed on anything, except that rocky road ice cream is tasty?

Second, whatever hinders marriage increases poverty. The Bible tells us that “it is not good for man to be alone.” The growth of single-parent families paralleled the growth of welfare in the 1960s and thereafter. Middle-class people generally don’t suffer financial penalties for getting married. In the income tax code, tax bracket cutoffs generally double for childless married couples filing jointly. Most couples pay the same amount they would if filing as single individuals. But in many programs for the poor—including SNAP, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and much of public housing—getting married can result in a loss of benefits.

A majority of state-level preschool programs also have marriage-discouraging penalties. Single moms can send children to preschool free of charge, but marriage often eliminates the entire benefit. In Texas, for example, a single mom earning $20,000 to $33,000 per year receives free preschool, but if she marries a man who makes another $23,000, she loses all her benefits. That’s a marriage penalty of more than $5,000.

Rules established at suite-level have street-level consequences. A 2016 American Enterprise Institute/L.A. Times survey asked men and women below the poverty line, “How often do you think unmarried adults choose not to get married to avoid losing welfare benefits?” About 24% of respondents answered, “Almost always,” and another 23% said, “Often.” In a 2015 American Family Survey, 31% of respondents said they knew someone who had chosen not to marry out of fear of losing “welfare benefits, Medicaid, food stamps, or other government benefits.”

Third, whatever emphasizes what we don’t have, rather than what we do, increases poverty. Question one should not be, “Do you have a physical, mental, or other health problem that limits the kind or amount of work you can do?” It should be, “What capacities or skills do you have?” What’s called ABCD—Asset-Based Community Development—emphasizes spending less time bemoaning deficits and weaknesses and more time identifying and honoring gifts, skills, and strengths. More on this below.

5. Is the road ahead different from what you outlined in your 1990s books?

The 1990s was an optimistic decade, with the Cold War ended, drops in crime in many cities, and good economic news: low inflation, increased wages and productivity, a near doubling of international trade, surging investment in developing countries, and a rising stock market. China entered the world economy, and many assumed it would move toward democracy.

I showed my lack of prophetic ability in several ways, however. First, I did not expect a 9/11-type of attack and the subsequent war in Iraq, nor the Great Recession that began in 2007. I thought race relations would continue to improve and did not sufficiently take into account the deindustrialization of parts of America. I did not expect declining attendance at churches, a trend that accelerated during the COVID years, with a concomitant decline in hope and less giving of ourselves.

Moreover, we’re certainly a lot more wary than we used to be. That has its pluses and minuses. My books certainly showed the opportunity for volunteers to make a difference but also warned against rushing in without understanding. Since then, many valuable books have come out with titles like When Helping Hurts. The books are right to distinguish between helping and hurting, but the danger is that some people might see all the mistakes and decide that the task is too hard even to begin.

We also have well-intentioned programs that do a lot of good but that may also bring harm. SSI is one of them. It became a program in 1972 as Congress moved to protect people with severe physical disabilities. That’s worthwhile, but thenpsychologists asked, Why not us? They argued that depression can be as disabling as a bad physical ailment. True enough, but while medical exams reveal tumors or crippling arthritis you can see, psychological ones are often judgment calls—which means that some folks can more easily game the system.

SSI is certainly needed for children who are disabled, but critics have pointed out what the National Bureau of Economic Research called the “perverse incentives for families to present their children as disabled, which could discourage the child’s human capital development.” Even the liberal Boston Globe reported that “the damage done to children who are misclassified as mentally ill is incalculable: Some linger in special ed classes when they are capable of accelerated work; others come to believe themselves to be impaired when no such impairment exists.”

A decade ago, reporter Patricia Wen, who now heads the Globe’s celebrated Spotlight team, interviewed a single mom who did not want to put her child on psychotropic drugs but realized, “To get the check ... you’ve got to medicate the child.” Wen tracked down a mother whose 2-year-old was on SSI after being diagnosed with speech delay and potential signs of autism. This mom described the cost to her spirit: “SSI sucks you in.”

Wen also talked with a 15-year-old who said she wants to work, but if she does “they’ll take money away from my mom. She needs it. I don’t want my mom’s money to go down.” Another young man said he wanted to work, but he’s “afraid to lose the check. It’s attached to me.” Wen quoted a psychologist saying that “children who grow up on SSI often cannot see themselves ever living outside the system. ... They develop an identity as being disabled.”

I haven’t found evidence that the SSI process has changed, and couldn’t find much newspaper coverage of it lately, so I emailed Wen and asked about new developments. She said she also hasn’t “seen much on the children’s SSI front.” This obviously needs more reporting. In the movie Forrest Gump, Forrest has below-average intelligence, but his mother always tells him, “You’re not stupid.” We have a problem if mothers tell children of average intelligence, “You are stupid,” to claim a check.

Another example of help mixed with harm is the biggest welfare program, SNAP: 41 million Americans—one out of eight of us—is on it. We don’t want to treat adults as children by telling them what they cannot buy. One result: the Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics found that SNAP participants consumed 43% more sugar-sweetened beverages than people similar demographically and economically but not on SNAP. They also consumed much more highly processed food.

Many scholarly articles about this have titles like “The Relationship Between Obesity and SNAP” or “Ending SNAP Subsidies for Sugar-Sweetened Beverages Could Reduce Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes.” My favorite headline is “Thin Wallets, Thick Waistlines.” The academic research continues to remind me of the title of a book by the Wall Street Journal’s Jason Riley: Please Stop Helping Us.

Structural problems may contribute to this. Some people live in food deserts—neighborhoods without supermarkets. Some people work hard and feel too tired to cook, so they buy unhealthy microwavable stuff. Calories do represent energy, and some people with a limited budget try to get the most short-term energy bang for their buck, regardless of long-term consequences.

Nevertheless, shouldn’t we have truth in labeling? I went through the 50 state websites and saw most frequently an explanation like this one from Arkansas: “The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) helps people with low income get the food they need for good health.” No, it doesn’t. The Illinois website says SNAP exists to “help low income households buy the food they need for good health.” Nope. New Hampshire: “The Food Stamp Program is about good nutrition and health.” No, it’s not.

All this means I’m not sure about the road ahead. My beliefs about what the road should look like have not changed: we should emphasize the literal meaning of com-passion, “suffering with,” and be willing to love our neighbors as ourselves. I don’t know how practical that is, but I can see a starting point: tell the truth. Beyond that, I could speculate that American compassionate conservatism picks up speed when the economy is strong, foreign enemies seem weak, and many people (usually for religious reasons) feel they should help others. The 1920s and the 1990s were decades that had those characteristics. Maybe such a time will come again.

We have a problem if mothers tell children of average intelligence, ‘You are stupid,’ to claim a check.

In the meantime, we have to settle either for living in a very mean time or building alliances among groups on both the right and the left that emphasize decentralization. I used the term “compassionate conservative” in the 1990s to distinguish that movement from large-government liberalism, but “conservative” turned into a limiting device. If compassionate conservatism has a comeback, it will do so as part of a larger movement that won’t merely be conservative but will involve libertarians, localists, and some among the other L-word—liberals.

There are three organizations in particular that compassionate conservatives should get to know.

One is the Christian Community Development Association (CCDA), a network of hundreds of urban groups. It’s not conservative but is committed to localism. The CCDA is based on the teaching of John Perkins, now 93, who survived beatings during the civil rights era and came out of that experience with an understanding that we are all “one blood.” When I interviewed him two years ago, John noted that the Christians described in the book of Acts “didn’t sit at home waiting for food to come by chariot. They went out to homes and started classes. They taught we are justified freely by His grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus.”

A second group, Strong Towns, is not a conservative organization, but it states, “We work to elevate local government to be the highest level of collaboration for people working together in a place, not merely the lowest level in a hierarchy of governments.” Strong Towns emphasizes “incremental investments (‘little bets’) instead of large, transformative projects.” It emphasizes “bottom-up action (‘chaotic but smart’) and not top-down systems (‘orderly but dumb’).” It aspires to work at a human scale instead of building bureaucratic dinosaurs.

As for the third, one year after The Tragedy of American Compassion came out, John P. Kretzmann and John L. McKnight published Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path Toward Finding and Mobilizing a Community’s Assets. I missed it at the time, but I’m now convinced that Asset-Based Community Development is important and a way for the left and right to work together. In addition, McKnight’s 128-page book, Associational Life: Democracy’s Power Source (2022), is a quick introduction to his thinking: it features short essays on “the role of citizens when they come together in associations that nurture and amplify their power to be productive creators.”

McKnight, who co-founded the Asset-Based Community Development Institute at DePaul University, writes, “The anger we observe nationally grows significantly from the dissatisfaction millions of people feel because they are locally disconnected from each other.” That’s true, and I’ll end on a note of practical philosophy about the beginning of a reconnect. Deuteronomy 15:7, 8 tells us what to do “if among you, one of your brothers should become poor ... You shall not harden your heart or shut your hand against your poor brother, but you shall open your hand to him.”

I like the specific detail of the biblical command: do not harden your heart or shut your hand. “Welfare” and “poverty” are abstract terms, but compassion begins when we see the suffering of one of our brothers or sisters. Philosopher David Naugle has pointed out that the Hebrew mindset emphasizes the concrete, whereas the Hellenic veers toward abstraction. Naugle says we should see with Hebrew lenses and live with Hebrew hearts. Agreed: We should emphasize street-level reporting rather than suite-level opining, and then open our hands.