Saint John Paul II famously said that the problem with pornography “is not that it shows too much of the person, but that it shows far too little.”

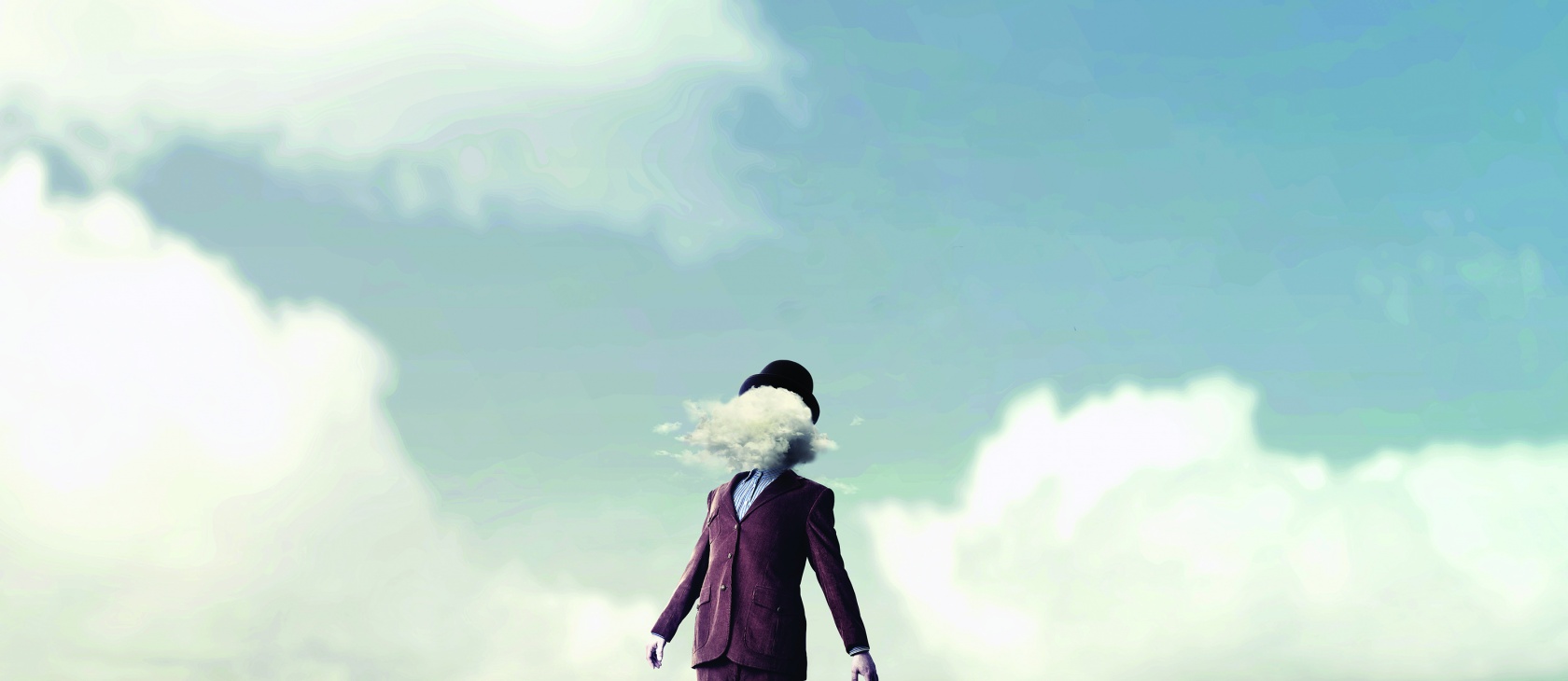

The pornographer, in presenting a woman fully exposed, obscures, rather than reveals, who she is. He measures her by her usefulness and totalizes that metric as the only lens through which she can be seen.

This is how ideology works, too. What the pornographer does to women, the ideologue does to all of reality. He has no desire to contend with the world as it is, but instead seeks only to use it to support his predetermined specifications. In so doing, he crudely diminishes it.

While ideologies can come in various forms, perhaps the most pervasive and threatening one on offer today is a repackaged version of the Marxist belief that all human dynamics should be analyzed through the lens of power. Persons are sorted into binaries of oppressor and oppressed. While Marx focused on economic relationships, in the “woke movement” the filter of oppression is expanded to include gender, race, and sexuality. This further reduces and categorizes people and exponentially spreads the societal fault lines.

The woke idealogue does point to real instances of injustice, but then deifies them into an omnipresent reality that defines and explains all that is. Every person, institution, and interaction must be interpreted in a manner that reinforces oppression narratives, regardless of whether such an interpretation is warranted.

A tenet of woke anti-racist reeducation, according to celebrated author Robin D’Angelo, is that in any given situation the question is not “Did racism take place?” but rather “How did racism manifest in that situation?” In other words, we must be trained to reframe all of reality in a way that conforms to ideology. D’Angelo is simply echoing Lenin’s point that the masses cannot of their own accord be sufficiently convinced of the depths of their oppression and, therefore, need an intellectual class continually prompting them to see in every social dynamic a fundamental struggle to either be dominated or to dominate. This is the groundwork of revolution.

Armed with this zero-sum filter, formerly nonpolitical spheres of life become battlegrounds of power: sex is political! And sports! Gardening, bird-watching, your friend’s afternoon barbecue … everything can be targeted as problematic for the ideologue whose only precondition for seeing that something is oppressive is that it exists everywhere.

In this light, being is not something to be received but something to be manipulated.

Human Nature

This ideological manipulation of reality not only claims to expose what is problematic around us but also what is problematic within us.

Foundational to any totalitarian system is the rejection of a stable human nature. The revolution comes to each individual by attempting to remake him in the image of a progressive utopian vision. We are socially constructed, so they say, and therefore can be reconstructed through social engineering and reeducation.

This totalizing ideology becomes so psychologically coercive that political loyalties can come to replace personal ones in brutal and inhuman ways. Children trained by the Soviet Youth Movement learned to reject their old bourgeois familial piety in favor of a fervid Party loyalty. Informing on one’s own parent to a murderous regime became an act of the highest honor.

Sexually transgressive activity is another way to demonstrate loyalty to ideology. The moral order is a meaningless concept for the ideologue, truth and morality being mere functions of power. Overriding one’s longing for marital fidelity or even one’s natural sexual inclinations is a necessary act of political liberation, albeit one that is often met with internal resistance. Male revolutionaries in the 1960s testify to having been ashamed that they were not easily able to overcome their inclinations toward heterosexuality. Surely, they thought, it was a result of bourgeois repression that they were disinclined to have sex with other men. Acts of self-restraint signified a failure of ideological purity.

A contemporary manifestation of this occurs in the shaming of heterosexual men who are unwilling to sleep with transgender “women” upon discovering that they are biologically male. The ideology holds that the trans person, despite having male biology, is truly a woman if he so identifies. The straight man who rejects a transgender person as a candidate for intimacy based on that biology must then be bigoted.

For the revolutionary, every transgressive act is a flag planted for liberty—a declaration of defiance against the concept of a moral order and even of bodily reality. Our stubborn bodies, which carry the implacable logic of law and nature, are something from which we must be freed. Should a man’s spoken identity as a woman come into conflict with his bodily reality, it is the body that must be rejected in favor of the ideology. Should a woman’s sexual freedom result in an unwanted pregnancy, again it is the body (hers and her child’s) that must be rejected.

Ideological power is only sustained by coercing individuals to internalize its lies and live in accord with them, at the expense of living in accord with reality.

Reverence

One problem with thinking ideologically is that it reverences nothing—not our heroes nor our history, not our human nature, nor even what is real and true. Dietrich Von Hildebrand wrote that “the most elementary gesture of reverence is a response to being itself.” Being docile to receive reality—to receive the world as it is given to us—is intimately connected to our ability to receive God himself.

How do we begin to think with reality in a way that compels us to reverence it? One thing we can do is struggle to see ourselves more clearly.

This is important for two reasons. Unvarnished self-knowledge is the sort of thing from which we tend to most recoil. Our egos have an endless capacity to deflect, excuse, and conceal our faults. Ideology capitalizes on this instinct to deceive ourselves. But it is in seeing ourselves with reality that we begin to become the sort of people who can see reality at all.

Secondly, if ideology is fueled in part by perpetual victimhood and the stoking of outrage at the perceived faults of others, a remedy is to contend with the faults of our selves. The person who strives to see his own inner world with clarity recoils at the prospect of presuming too much about the inner world of another. Without this perspective, those around us become cartoon renderings of heroes and villains based on surface attributes and group identification. We stop thinking deeply, and thus become vulnerable to sloganeering and propaganda. We see no need for mercy for ourselves, and so look mercilessly at the world around us.

Knowing ourselves with clarity helps us to see others with generosity. Many are experiencing the sting of division in friendships and families over the turmoil of the 2020s. Everyone—from any viewpoint—is susceptible to growing contemptuous of friends and family,

especially when the stakes are high and the consequences deeply felt. Hatred for an ideology can easily become hatred for the person espousing it, and this would be the true triumph of the very thing we think we are fighting.

We live in an ideological age and are prompted from almost every direction to use every event to further confirm us in our outrage. This provides us with an illusion of righteousness. Ideology exploits this very human tendency to find our virtue in identifying the vices of others.

The Christian disciplines of self-examination, contrition, and resolution are a corrective for this tendency. Such habits prompt us to direct our focus back to our own sins and see them, and ourselves, in light of a moral order and a merciful God.

“How can I use this person to serve my end of pleasure?” asks the pornographer. “How can I use this event, person, or tragedy to serve my preconceived political narrative?” asks the ideologue. Utopian ideology takes the scapegoating instinct, trains us in it, and then addicts us to it.

This cycle cannot be fought by simply becoming an ideologue of a different stripe. If the woke movement, like the Marxism before it, fundamentally manipulates reality, then its opposition must be disciplined in its humble reverence of it.

Ideology is compelling because it presents us with a passionate response to a real problem. That injustice exists is true. That the female body is erotic is true as well. Neither proposition comes close to being a comprehensive understanding of human persons or the world around us.

To see reality as it is, we must start with the hardest reality to face of all—that of sincerely seeing ourselves. Only then can we hope to look upon one another with humanity—with reverence for the true dignity of the other and reverence for the Being who is being itself.