Christians ended slavery. Do you think that’s a conservative simpleton’s mock-worthy bombast, embarrassing the rest of us with his black-and-white, unapologetic caricature of American history? No. It is the considered conclusion of a Nobel laureate, a former communist, a secular Jew, and arguably the foremost scholar on American slavery.

Robert Fogel (1922-2013), the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, was president of Cornell University’s American Youth for Democracy, investing eight years promoting communism. Meanwhile, he married Enid Morgan, an African-American woman, consequently suffering the ugliness of American racism personally. Eventually, he rejected communism. Apparently, the data didn’t support it.

Fogel was driven by data, perhaps the purest pursuer of empirical truth I’ve ever met in academia. He pioneered an approach to history, called “cliometrics,” that relied on quantifiable evidence; that is, countable documentation. Like any historian, he read diaries and pamphlets for the color they throw on the times, but for his conclusions, he sought hard facts. For example, whereas other historians might look to the likes of Fanny Kemble, a British actress who married a Southern plantation owner, to piece together the lives of the slaves, Fogel believed such sources were too filtered through bias. Campaigners, like Harriet Beecher Stowe, tended to dramatize. Cliometrians, though, seek government records, the business ledgers of plantations and the like.

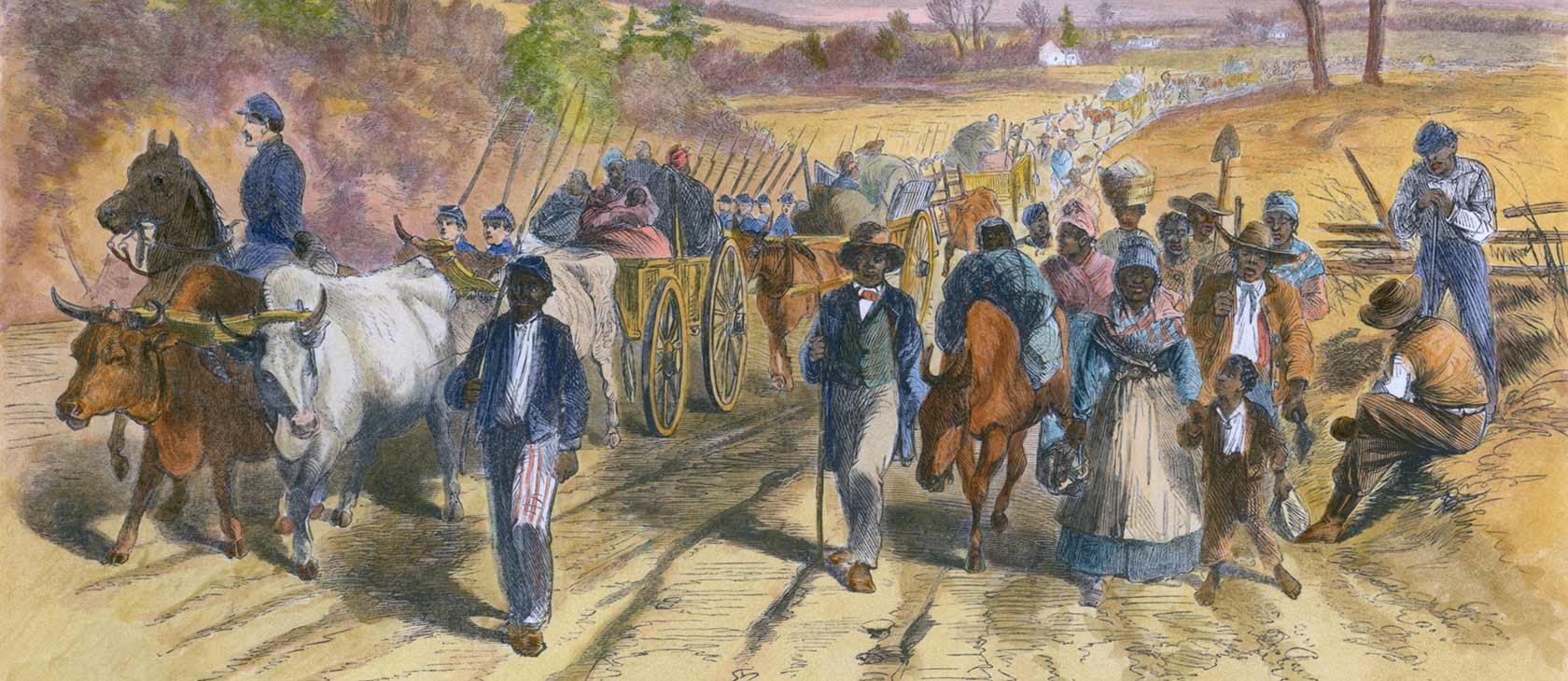

Slavery was on the ascendancy at the outbreak of the Civil War.

Fogel’s bean-counting approach led to his discovery that plantations, organized in a business-like fashion with their “gang system,” had an assembly line-like efficiency. Hence Southern slavery was fantastically profitable. He calculated, in his books Time on the Cross and Without Consent or Contract, that Southern slavery was 36% more efficient than free Northern farms even though, generally, the soil in the North is better. Propelled by slavery, the economy in the South grew twice as fast as the North’s in the decade prior to the Civil War. He concluded that if the Civil War had not been sparked when it was, the South would have continued to outpace the North, adapt slavery to industrialization, been unconquerable if a later Civil War had broken out, and likely would have spread slavery indefinitely. Slavery was on the ascendancy at the outbreak of the Civil War.

Furthermore – and here it sounds scandalous – most Southern slaves were treated materially well by their “owners.” The average slave consumed more calories and lived longer than the average, white, Northern city-dweller. Contrary to popular myth, slave families were rarely divided up -- only about 3% were -- and slave-owners rarely used their slaves for sexual indulgence, with only about 2% of slave births being by white fathers. Because of these superficially positive findings about slavery, some critics misunderstood Fogel and attacked his work. But it withstood the criticism, earning a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 1993.

The moral question: If Southern slavery was profitable, even providing for the slaves a relatively decent material life, then why is it evil? If slavery is wrong, then, we have to look beyond the beans that can be counted, the dollars that can be earned, the efficiency that can be charted. The answer is found in a system of morality that comes from beyond mere materialism.

Fogel saw that the American institution of slavery was evil because it depends on unrestrained domination. One group of people determine, in God-like fashion, the fate of others. Slavery was, for Fogel, a “Time on the Cross.” This was the original objection of Christian abolitionists and that caught Fogel’s eye. Christians provided the other-worldly ethics that ended a system that worked in this world that had been normal. But Christians believed that normalcy and efficiency were no excuse if it offended the next world.

Fogel was so convinced that evangelicals had been a force for good in America that by 2000 he wrote The Fourth Great Awakening and the Future of Egalitarianism. In it he argued that Christians will lead America, once again, toward moral progress. I took his class at the University of Chicago, as an evangelical learning from a self-professed secular Jew. I wrote a paper in which I argued that he was wrong about the present and future. He invited me to his office and plied me with questions. I didn’t change his mind but the next year he invited me to be his teaching assistant. He tasked me with presenting the lecture on his findings on slavery. During one after-class chat, he told me that he was astounded to discover that Christians ended slavery. He said something like, “Here I was, a professor in some of America’s leading universities and I had no idea that Christians had done that.” Fogel concluded that it was not economic forces that brought about the end of slavery but a moral revolution rooted in Puritanism. Christians, mainly from Puritan New England and Quaker Pennsylvania, turned the tide of popular opinion in the North against slavery. Remember, originally every state was a slave-state. Slavery was normalcy for America too at its founding. That changed because Christians increasingly agreed that slavery was evil, transforming what had been a slave-holding country into a house divided.

It was not economic forces that brought about the end of slavery but a moral revolution rooted in Puritanism.

Today some Christian intellectuals scold the church for being complicit in slavery. They’re right, of course. But only half right. What they fail to see is that slavery was a universal human institution for all history. Normalcy. It’s impossible to isolate one group as responsible for it because all were. If we go back in anyone’s ancestry far enough, we’re almost certain to find a slave owner. We’re all the sons and daughters of slaves and enslavers. The question is not who enabled slavery. Everyone did. The questions is, who, after millennia of this fallen institution, stopped it. Today, many Christians don’t know enough of their heritage to answer that question.

Our legacy of ending slavery shouldn’t be so buried. William Wilberforce and John Newton, of “Amazing Grace” fame, are favorite sermon illustrations. Lesser known is the fact that one of the earliest books against slavery in the Anglo-American world, The Selling of Joseph (1700), was written by a Puritan, Samuel Sewall. A Quaker anti-slavery book preceded it by just a few years. Jonathan Edwards is often condemned for owning slaves. Lesser known is that his disciples, like Samuel Hopkins (1721-1803) and his own son, were founders of the abolition movement. Jonathan Edwards the younger, on September 15, 1791, gave an impassioned sermon, based on Jesus’ golden rule, condemning slavery. The theological movement birthed by Edwards and the Great Awakening, the New Divinity, inspired ministers who denounced slavery in their evangelistic preaching. The Christian roots of other abolitionists, from Britain’s Granville Sharp, to John Wesley, to Charles Spurgeon, and America’s Tappan brothers, who with William Lloyd Garrison founded the American Anti-Slavery Society, should be recounted in our churches and our apologetic conversations. Christianity’s commitment to freedom was so pronounced that Frederick Douglass, who decried the hypocrisy of slave-holding religion vividly, did not convert to Islam and become “Frederick X,” but professed, “I love the religion of our blessed Savior.”

Sure, there were plenty of professed Christians – and regrettably some real ones – who defended slavery to the end. Robert Lewis Dabney (1820-1898), an otherwise orthodox Presbyterian theologian, wrote a defense of slavery so unashamed even erstwhile Confederates were embarrassed by it. There’s no excuse for such complicity with slavery, especially so late in history. But Dabney and Robert E. Lee and the pious Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson take their place among the normal of history. Slavery had been the norm, business as usual. What is striking is when normalcy is disrupted, the bolt from the blue. Abolition was that bolt, a revolutionary shock breaking into history. Where did it come from? It wasn’t the long arc of history inevitably bending toward progress. It was a transformation from above.

The former communist Nobel laureate proved how Christianity freed the slaves. Sure, we have normalcy to be ashamed of. But, more remarkably, we have the miracle to be proud of.