Earlier this year, Susan Mettes of Christianity Today critiqued the use of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a ministry tool. The central idea of the hierarchy, as Mettes puts it, is “that physical needs must be met before people experience spiritual needs.” Mettes argues against such a dualistic perspective, and instead points out that the Bible places a priority on spiritual and eternal realities even as there is a kind of interactive and dynamic relationship between material and spiritual needs. As Mettes writes, “We know that which eating, drinking, and sleeping habits are spiritually damaging often depends on individual consciences and situations. However, there is a first step: to value spiritual life.”

Apart from the value of Maslow’s particular understanding of human needs, and the various uses it has been put to in ministry as well as popular contexts, the challenge to rightly relate the temporal and the eternal, the material and the spiritual, is as old as the gospel itself. Maslow’s hierarchy, in this way, is a contemporary manifestation of a solution to an age-old problem. And the idea that there is some sense in which material needs must be met before spiritual needs can be properly addressed is, indeed, much older than Maslow.

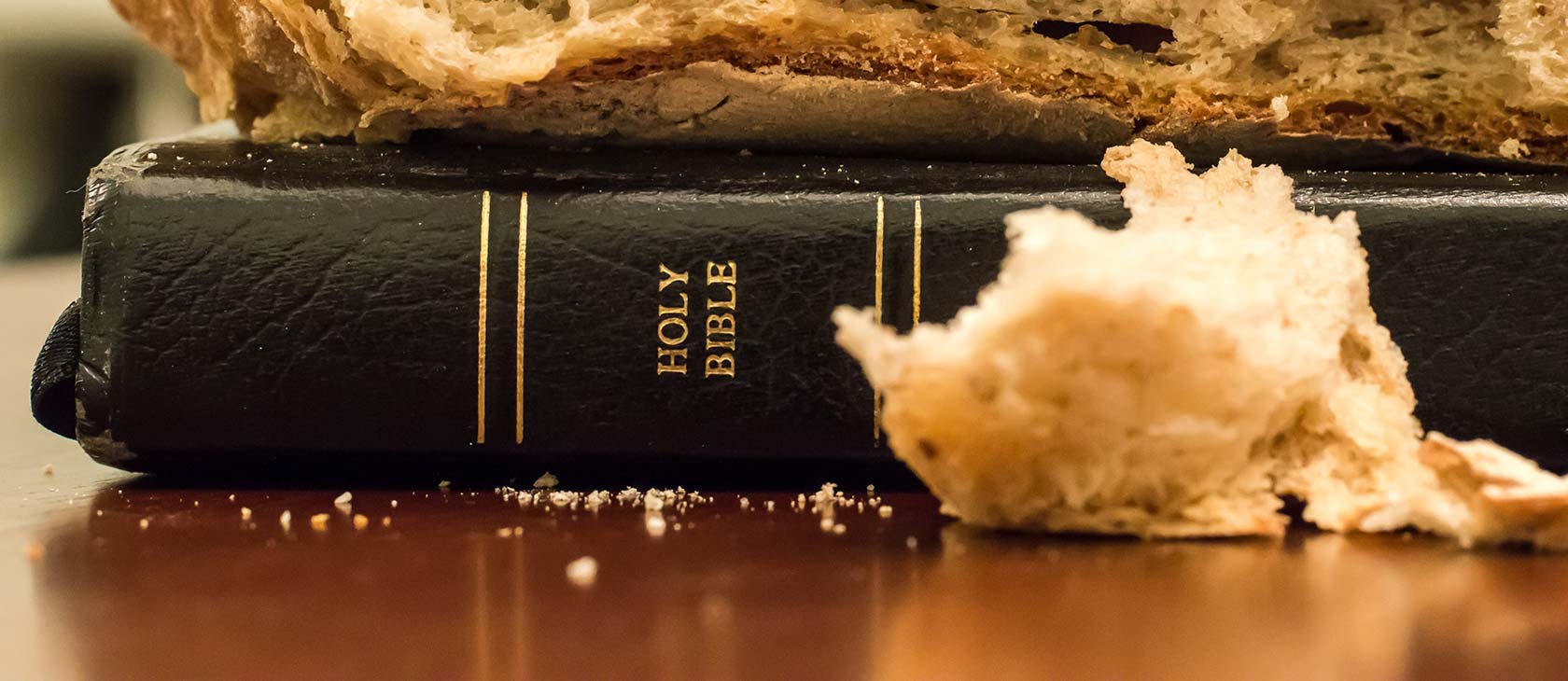

The Lord’s Prayer has us petition for daily bread followed by forgiveness of sins. The 17th century Puritan Richard Baxter reflects on this, and concludes, “We pray for our daily bread before pardon and spiritual blessings, not as if it were better, but that nature is supposed before grace, and we cannot be Christians if we are not men.” Baxter wrote this in 1682 as part of a treatise focused on discipleship, particularly the responsibility of the follower of Jesus Christ to “do good to all” (Gal. 6:10). To do good to all people requires a proper understanding of the relationship between material and spiritual needs. As Baxter’s exposition indicates, this is another way of putting the challenge of properly relating nature and grace, or creation and redemption.

Human beings are created with bodies and souls. We have both material and spiritual needs.

Baxter’s understanding mirrors a traditional Christian response: Grace presupposes and in some sense builds upon, completes, perfects, or restores nature. Human beings are created with bodies and souls. We have both material and spiritual needs. Or as Baxter continues, “God has so placed the soul in the body that good or evil shall make its entrance by the bodily senses to the soul. God himself conveys many of his blessings this way, and this way he inflicts his corrections.” The practical, pastoral conclusion is this: “Do as much good as you are able to men’s bodies in order to the greater good of souls. If nature be not supported, men are not capable of other good.” This insight is part of the reason the early church developed a diaconal ministry separate from, but not absolutely unrelated to, the proclamation of the gospel (Acts 6). If people keep clamoring for food during the sermon, the people better get fed and not just with spiritual bread.

There is, in this way and in some sense, a temporal or practical priority of material needs in relationship to spiritual goods. But as Mettes’ article shows, this isn’t the only order of priority that is important. As the older Christian tradition would observe, there is a difference in the order of time and the order of being, or as Baxter describes it, there is a distinction between the “order of estimation” and the “order of execution.” Material goods and needs may require prioritization in the order of execution even if they are secondary according to the order of estimation.

This kind of distinction, and the corresponding responsibility to rightly order material and spiritual needs, is fundamental to the New Testament teaching about the gospel and the kingdom of God. Material needs and realities are clearly not dispensable or mere annexes to the gospel. But neither are they all that is important. Material liberation and prospering do not exhaust the gospel’s holistic scope. The relationship between material and spiritual goods is thus a both/and rather than an either/or and it is perhaps the great challenge of the Christian life is to discern the proper valuation and interrelationship of material and spiritual goods.

This is, after all, how Jesus himself describes it in the Sermon on the Mount. Following his teachings in Matthew 6 about how to pray and how to fast, activities which encompass both material and spiritual realities, Jesus instructs his hearers, “Do not be anxious about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, nor your body, what you will put on.” Why not worry about such necessities? Jesus addresses the question with a question: “Is not life more than food, and the body more than clothing?” It is not that food, drink, and shelter are unimportant. We are bodily beings, and such matters are clearly significant for us and for our lives. Even so, we are created for more than material goods, and in light of this our concerns, worries, and devotion should be rightly ordered.

We pray to God for our daily bread and our material needs because, in part, as Jesus puts it, “your heavenly Father knows you need them all.” But such penultimate, temporal concerns have to be properly related to ultimate, spiritual realities. As Jesus concludes, “Seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be added to you” (Matt. 6:33). When evaluating whether a model such as Maslow’s hierarchy is a help or a hindrance to Christian ministry, it is absolutely essential to have the proper relationship between nature and grace, between material and spiritual needs. Only this will allow us to do justice to the gospel in its all-encompassing splendor and radical implications for both this world and the world to come. Or as Baxter concludes, a life spent in service of the King of kings and Lord of lords “is the life that need not be repented of as spent in vain.”